Last week, a news channel based in Singapore quoted the country’s Early Childhood Development Agency (ECDA) as saying that about one-fifth of childcare centres in Singapore will charge higher fees next year.

Later, in an interview with the same news channel, Manpower Minister Josephine Teo said that there was “some fairness” in these 330 child centres raising their fees. According to Teo, this was because the fees among childcare centres, even those under the same operator, could be “quite different” despite having similar resources.

“Sometimes for historical reasons, the fees are quite different … when in fact the teachers are just as qualified (and) the centres just as well-resourced. So there is some room, some fairness in them harmonising the fees,” she was quoted as saying.

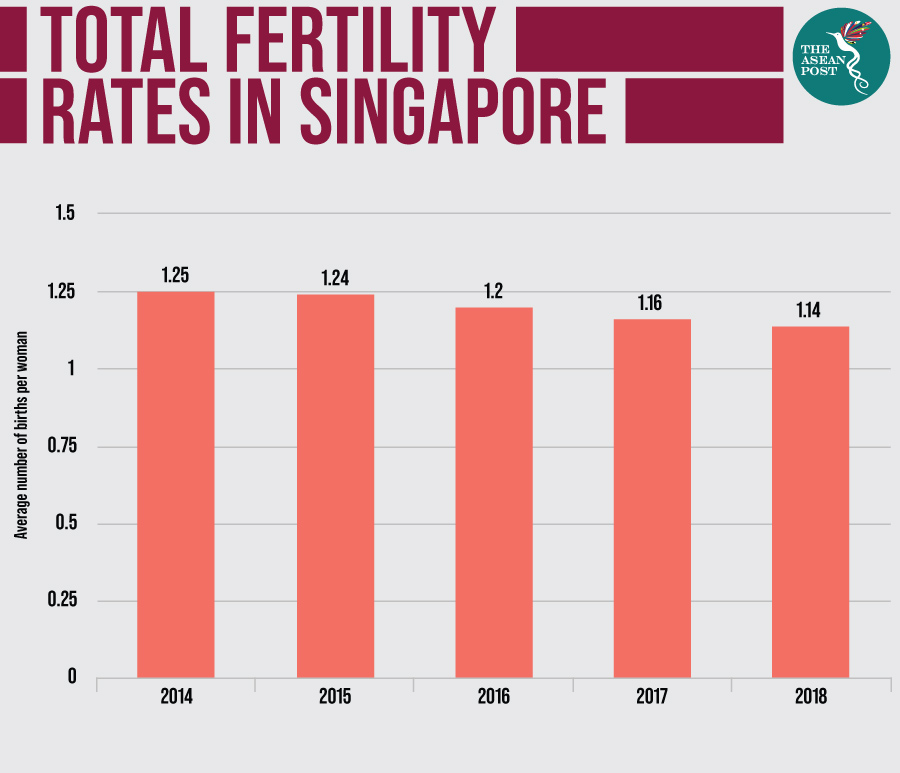

The higher fees are important because Singapore is an ageing country. This fact is further exacerbated because of its dwindling fertility rate, a number that has continued to drop since 2014.

In March 2018, Teo revealed that Singapore’s total fertility rate (TFR) dropped to 1.16 in 2017, making it the lowest figure since 1.15 in 2010 and the second lowest ever recorded for the country. Statistics on the TFR - which measures the average number of children per woman - have been available since 1960. The 1.16 mark continues a declining trend since 2014 (1.25), 2015 (1.24) and 2016 (1.20).

In March this year, the Ministry of Manpower (MOM) revealed 2018’s TFR. The TFR dropped again to 1.14 in 2018 according to preliminary estimates, the lowest TFR ever recorded in Singapore since records began in 1960. The numbers are much lower than the replacement rate of 2.1.

The ECDA’s statement came shortly after Singapore’s government announced that there would be additional pre-school subsidies on 28 August. The subsidies aim to provide more support for low to middle-income parents. For example, families with a gross monthly income of S$3,000 will pay S$3 a month, down from S$70, per child at anchor operator pre-schools.

It is more than likely that one of the reasons for this announcement was to encourage more Singaporeans to have babies. In July, the Straits Times posted its article entitled “Number of babies in Singapore drops to 8-year low” on its Facebook page. Many of the people commenting on that post blamed the high cost of living for the low birth rates.

Associate Professor Kang Soon-Hock of the Singapore University of Social Sciences was quoted as saying that the birth numbers show the current socio-economic trends, where a large group of young people choose to be single and couples delay their plan for marriage and parenthood.

Similarly, Professor Jean Yeung, director of the Centre for Family and Population Research at the National University of Singapore (NUS), was also quoted as saying that increased uncertainties due to digital disruption, global financial uncertainty and climate change also contributed to the situation.

“(These factors) might prompt couples to think even more carefully about whether to bring a baby into the world or not. The median age of resident live births for first-time mothers was 30.6 years last year, compared with 29.7 years in 2009. This itself is a cause for concern,” Yeung was quoted as saying.

When Teo was asked by Singaporean media whether she was keeping a close eye on the fee revisions as they could potentially affect or negate the subsidies, she replied that a large majority of these childcare centres planning fee hikes are government-supported, and their fees remain below the stipulated limits.

The Government provides funding to anchor and partner operators, which in turn are required to keep their fees affordable by adhering to monthly fee caps. Full-day childcare fees, excluding Goods and Services Tax, are capped at S$720 a month for anchor operators and S$800 a month for partner operators. In addition, government-supported childcare centres can only make fee adjustments of no more than 5 percent each time.

It is important that Teo’s assurances are highlighted because while they serve to tell Singaporeans “don’t worry, it’s still going to be cheaper now”, the very fact that many childcare centres are going to increase their fees may turn even more Singaporeans off from having children. This will be a battle for the Singaporean public’s perception.

Related articles: