If the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) were a single country, its approximate population would be a staggering 630 million, making it the fourth largest in the world behind India, China and the European Union. Economic growth is impressive, with an average annual real growth rate slightly higher than 5 percent. Coupled with a young population – where 60 percent are below the age of 30 – this translates to an immense potential in labour.

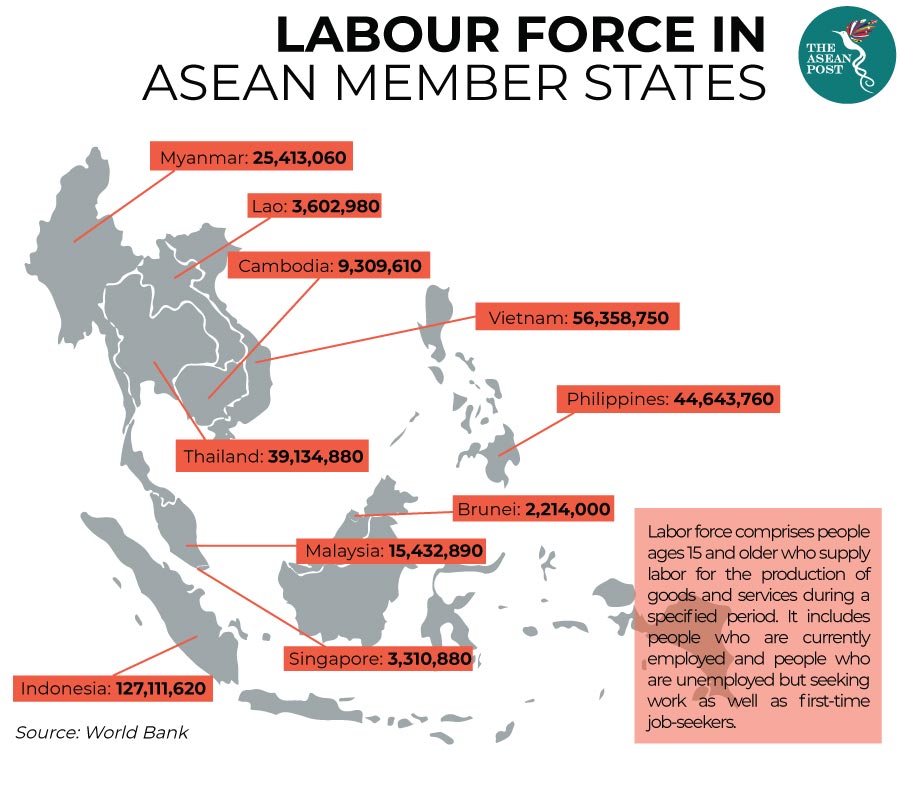

The association has the third largest labour force in the world behind China and India. Current World Bank estimates place ASEAN’s labour force at, 350.5 million. In order to make full use of the wealth of labour, ASEAN member states must do more to realise its economic ambitions.

The problems with the workforce

In a commentary published by the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Senior Analyst with the Centre for Multilateralism Studies (CMS), Phidel Vineles, argues that the region – especially the ASEAN-5 (Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia, and the Philippines) – lack industry-ready skilled workers in spite of its vibrant demography.

In Singapore, Vineles cites the nation’s dependence on foreign workers and a lack of innovation in the Singaporean education system as primary challenges to its labour force. Malaysia and Thailand, face similar challenges in equipping their respective workforces with engineering and science skills. Besides that, Indonesia and the Philippines have high youth unemployment rates due to a workforce that is ill-equipped with skills and knowledge needed by key industries. Brunei, which is moving away from oil dependence to a knowledge-based economy is finding it difficult to equip its labour force with necessary research and development skills. CLMV (Cambodia, Lao, Myanmar and Vietnam) economies, broadly lack coherent technical education which is necessary for industrial development.

Finding a solution

The burden of finding a solution to this conundrum lies within the domain of the government and private sector. According to Vineles, since both depend on a skilled labour force, cooperation by both sides is necessary in ensuring the workforce is industry-ready and competitive.

Coordination between the public and private sectors is necessary in order to help private enterprises meet skill demands. The government should play facilitator and also provide incentives to private companies that provide training to their employees.

However, given ASEAN’s young demography, attention must also be paid to those seeking job opportunities after completing their education. The problem with employing such individuals is a lack of work experience which can often be bridged by internship programs that are tailored to meet the skillsets required by employers.

An example of such an initiative is the Structured Internship Program in Malaysia, run by government agency, TalentCorp. The aim of the program is to ensure new entrants to the workforce are more employable in order to fill-up talent shortages in the country. To motivate companies to partake in the program, they are offered double tax deduction incentives. Companies that are included in the program include internationally recognised firms like PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), Schlumberger, The Neilson Company and Deloitte.

Cooperation across the board – by the government and industry players – would be useful when determining emerging skills that are required by particular industries. Vineles points to skills required by small and medium enterprises which provides between 60 and 97 percent of employment in the region.

“Strengthening the skills of the SME workforce should partly be by encouraging multinational companies and corporations to provide training schemes for them, especially that some of these enterprises supply components to the international manufacturers,” he added.

Besides that, governments should also emphasise the importance of technical and vocational education and training (TVET). It would help youths develop necessary skillsets so that they would be industry-ready upon entry into the workforce.

As ASEAN develops its workforce, ambitions for greater regional mobility can be realised. What the region has is immense potential, but worries that unskilled labour would flood certain countries if mobility laws are relaxed, is an understandable concern. The way around is to empower the population and increase their employability so that they become attractive options for employers throughout the region. In doing so, we can unlock new ways for the region to develop and grow.

Related articles

Philippines, the most dangerous country in Southeast Asia for journalists

Bank Indonesia signals no more rate cuts as inflation risks rise

Digital Payments: Can foreign providers overtake local providers in Southeast Asia?