Southeast Asia has been touted as one of the most dynamic regions which is projected to enjoy increased development and high economic growth rates in the coming years. To keep the cogs of industry turning within the region, there must be adequate supply of electricity.

Electricity demand in member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) is expected to grow between 5 to 6 percent yearly from 2016-2020. In recognition of this surge in demand, the idea of an ASEAN Power Grid (APG) was mooted in 1997, as part of the ASEAN Vision 2020.

What is the ASEAN Power Grid (APG)?

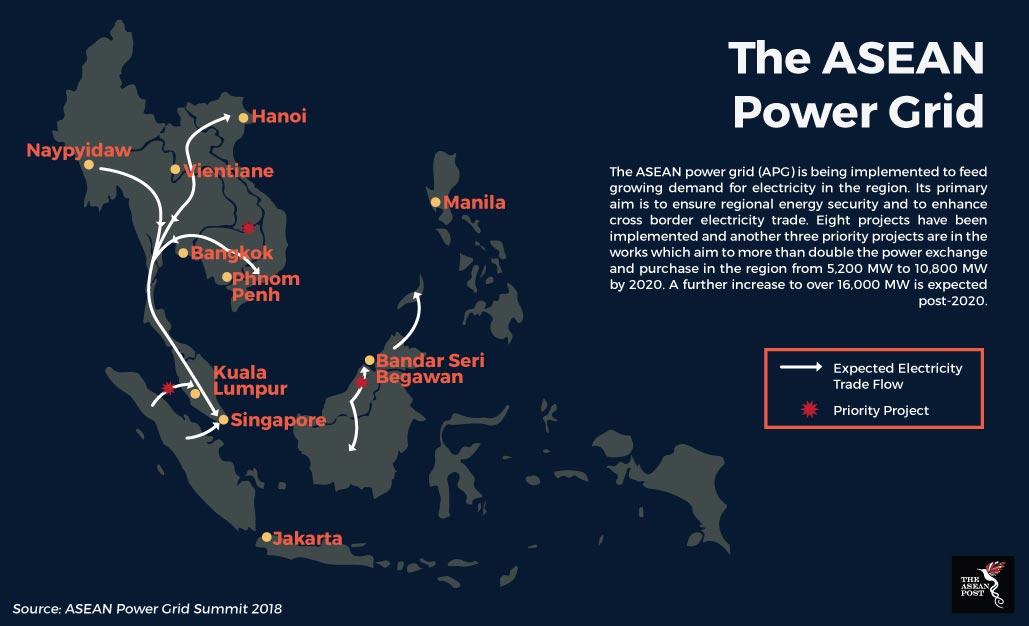

The APG aims to ensure regional energy security and enhanced electricity trade across borders. This would complement the rise in electricity demand and also improve electricity access in rural areas within the region. Its implementation is done on three levels. First, on cross-border bilateral terms, then it is expanded to a sub-region basis and finally, to a total integrated regional system.

The entity tasked with delivering the APG is the Heads of ASEAN Power Utilities/Authorities (HAPUA) which acts as a Specialised Energy Body (SEB). It achieves this via the ASEAN Power Grid Consultative Committee (APGCC) that aims to develop a common ASEAN policy on power interconnection and trade which would subsequently lead to the realisation of the APG.

Currently, the interconnection projects are on a cross-border bilateral basis. Eight projects have been implemented thus far with a power exchange and purchase of 5,200 megawatts (MW). However, in a joint statement released by HAPUA Council Members in September last year, three priority projects are being pursued which would double exchange and purchases of electricity to 10,800 MW in 2020 – and beyond 16,000 MW post-2020.

As the APG progresses, it is beginning to evolve beyond bilateral exchanges to sub-regional multilateral power interconnections. The Lao PDR-Thailand-Malaysia-Singapore (LTMS) Power Integration Project (PIP) would be the region’s first such endeavour. Its first phase is currently being implemented starting early this year.

Last September, Malaysia inked an Energy Purchase and Wheeling Agreement (EPWA) with Lao and Thailand. The deal will see Malaysia purchase up to 100 MW of hydro power from Lao via Thailand’s existing transmission grid starting this year.

Malaysian Energy, Green Technology and Water Minister, Maximus Ongkili said that the deal would benefit the country due to the competitive pricing compared to other sources. The purchased 100 MW would be a reserve source of energy that will also enable Malaysia to improve its share of sustainable energy which currently stands at 22.5 percent of the total energy mix.

He also lauded the agreement as a milestone for the region’s energy trading.

Regional impact of APG

The LTMS PIP is a step in the right direction for ASEAN member states as the APG is slowly brought to life. Leaders of ASEAN member states must come to realise that their countries stand to benefit vastly from this region-wide undertaking.

Electricity exporters like Cambodia, Lao and Myanmar could see increased export earnings from export-oriented hydropower projects. This can be a potential attraction point to lure investors to pump capital into future hydropower ventures.

Electricity importers like Brunei, Vietnam, Philippines, Thailand and Singapore will be more energy secure and reduce their dependence on gas-fired and coal-fired power plants. This would also help diversify their power supply mixes.

Countries like Malaysia and Indonesia which are both importers and exporters of electricity also stand to benefit. In Malaysia, electricity trade could boost potential hydropower generation in its state of Sarawak. In Indonesia, grid connections between its territory of Kalimantan and Sarawak could reduce dependence on expensive diesel fired generation.

To the layman, better electrical connectivity would see higher electrification rates especially in rural areas. With more and more people connected to the national grid and having stable access to electricity, it would lead to further urbanisation. The poor can be lifted from their downtrodden socio-economic stature as the resultant industrialisation would see more job opportunities leading to better productivity and improvements to the nation’s Gross Domestic Produce (GDP).

As Southeast Asia becomes the centrepiece for East Asia, better access to electricity will be a game changer – making it possible for ASEAN member states to achieve and go beyond their growth targets.

Perhaps the modern adage should be amended – with great power, comes greater economic prosperity for us all.

Recommended stories: