Indonesia, the world’s fourth most populous nation, and 10th largest economy in terms of purchasing power parity, has made enormous gains in poverty reduction – cutting the poverty rate by more than half since 1999, to 9.78 percent in 2020.

Nevertheless, out of a population of 270.2 million, an estimated 26.42 million Indonesians still live below the poverty line. Without a significant expansion of social assistance, five to eight million more Indonesians could be pushed into poverty because of COVID-19 shock.

With around 40 percent of Indonesia’s palm oil owned by smallholders – mainly in Kalimantan, Sumatera and Sulawesi – the palm oil industry has a lot of potential for Indonesia to achieve the United Nations’ (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

The SDGs, which are targeted to be achieved by 2030, including eliminating poverty, growing affordable and clean energy, climate action, and eradicating hunger.

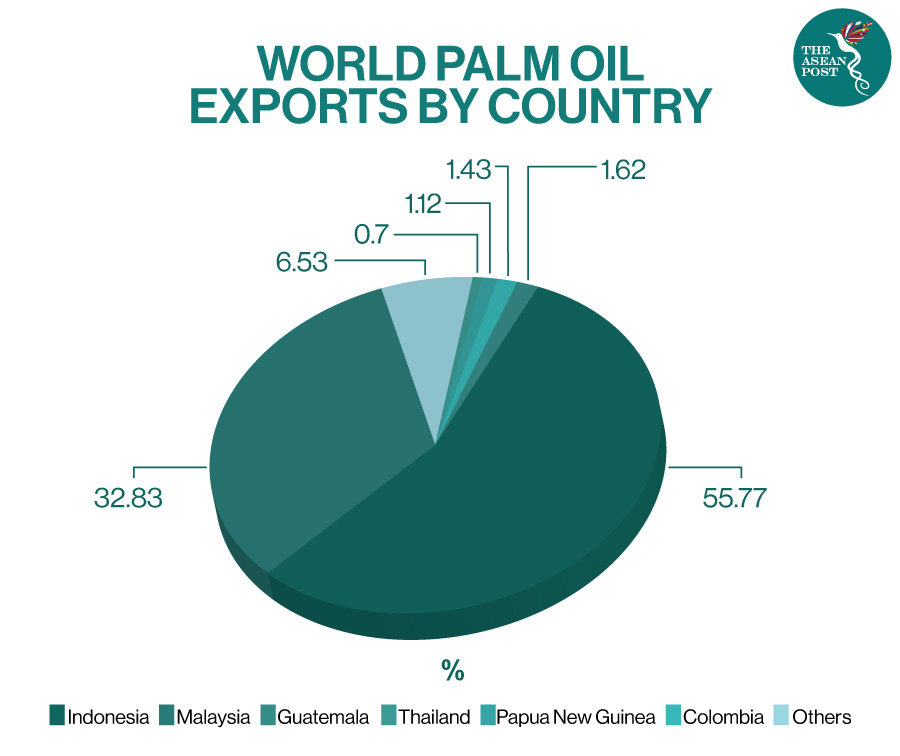

The palm oil industry has helped lift millions of people out of poverty, both in Indonesia and Malaysia, which together account for around 85 percent of global production. Oil palm plantations have created millions of well-paying jobs and enabled tens of thousands of smallholder farmers to own their own land.

However, the European Union’s (EU) sanctions on Indonesia to halt palm oil imports in 2020 is indeed problematic. The reason for such action as mentioned by the parliament of the EU is related to human rights issues such as child labour, the omission of the rights of indigenous people, and deforestation and habitat damage.

As the contribution of Indonesia’s crude palm oil (CPO) exports to Europe is only 14 percent of total CPO exports, there were no significant impacts found in the suspension of palm oil exports on Indonesia by the EU. Nevertheless, the government of Indonesia should consider protecting the development of its palm oil industry from the violation of human rights and deforestation.

Analysis

Indonesia, as one of the leading producers of crude palm oil, has been successful in serving the domestic and world market with palm oil-based products and palm derivatives. The industry contributed US$5.13 billion to foreign exchange savings in 2020.

Several studies have shown that palm oil is an important contributor to Indonesia’s economic growth. Therefore, disruption in this sector will inadvertently affect other sectors of the economy as well.

For instance, according to a 2004 research paper titled, “Contribution of oil palm industry to economic growth and poverty alleviation in Indonesia,” the author Wayan R Susila found that the industry contributed to the archipelago’s economic growth and has a significant impact on alleviating poverty and income distribution within society.

The same result was obtained by another researcher in 2015 who showed that the expansion of palm oil’s share of land in the 10 districts that experienced the largest expansion would decrease the poverty rate and narrow the income gap.

In 2019, it was estimated that the palm oil industry had succeeded in lifting 2.6 million rural Indonesians out of poverty.

While at the regional level, Gatto et al. in 2017 showed that contracts between smallholder palm oil farmers and private or state-owned companies significantly contributed to the regional economy especially at the village level in the form of infrastructure built. This not only benefited contract farmers but also non-contract farmers as well.

However, if mismanagement happens, the production of palm oil can result in land grabs, loss of livelihoods and social conflict. Moreover, human rights are often violated at plantations. The resulting conflicts could have a significant impact on the social welfare of many. Clearing land for plantations also involves burning rainforests, and in the process – endangering rare species and releasing 100 times the greenhouse gas (GHG) of conventional forest fires.

Moreover, in Indonesia, there is limited oversight by labour authorities due to lack of enforcement capacity and the remote location of many plantations. This also contributes to child labour in the palm oil sector.

Recommendations

The development of a green economy in the palm oil industry should be based on three aspects namely: economic, social and environmental.

First, under the economic aspect, legal tools need to be developed together with building implementation capacity to strengthen management in areas with land of high conservation value but zoned for agricultural use.

Second, ensuring the social aspect that focuses on developing measures to safeguard community benefits during the implementation of smallholder partnership agreements is in accordance with negotiated terms and conditions. In addition, job creation or other forms of community livelihoods support during the period when palm trees are maturing should be agreed upon between companies and communities.

In order to tackle the issue of child labour in the palm oil industry, further improvement of government policy is needed. This can be achieved by improving compliance among plantations, strengthening monitoring systems, conducting labour inspections and providing grievance mechanisms.

Last but not least, there must be minimal to no impact on the environment with a balanced eco-system, efficient use of resources, use of alternative energy such as solar energy, biomass energy, and wind energy to replace conventional energy, and the use of environment-friendly technology.

Together, to achieve Goal 1 of the SGDs which is eradicating poverty, there should not be any human rights violations and destruction to habitats or environmental damage.

Related Articles: