At first glance, one can see similar motives for the 2006 and 2014 coups in Thailand as well as the 2021 Myanmar coup.

In all three cases, coup-plotters faced popular civilian governments seeking more control over the military.

In 2006, General Sonthi Boonyaratglin confronted Thailand’s populist Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra. In 2014 General Prayut Chan-o-cha faced-off against Thaksin’s sister, Yingluck.

In 2021, Myanmar military commander Min Aung Hlaing confronted Aung San Suu Kyi.

With their compulsory retirements drawing near, these military leaders could have faced prosecution and lost their economic holdings as well as any political future.

Indeed, Thailand and Myanmar are both praetorian societies given that their militaries have always been leading national political actors.

In the name of national security, these militaries have possessed enormous state, economic and social power. When elected civilian governments led these countries, civil-military relations in Thailand and Myanmar have been fraught with extreme tension, often leading to coups.

Thailand Could Have Been A Model For Myanmar

General Min Aung Hlaing and other Tatmadaw leaders were certainly watching and taking notes when Thailand’s 2014 coup against a popularly-elected civilian democracy sustained itself into a military-dominated pseudo-democracy in 2019.

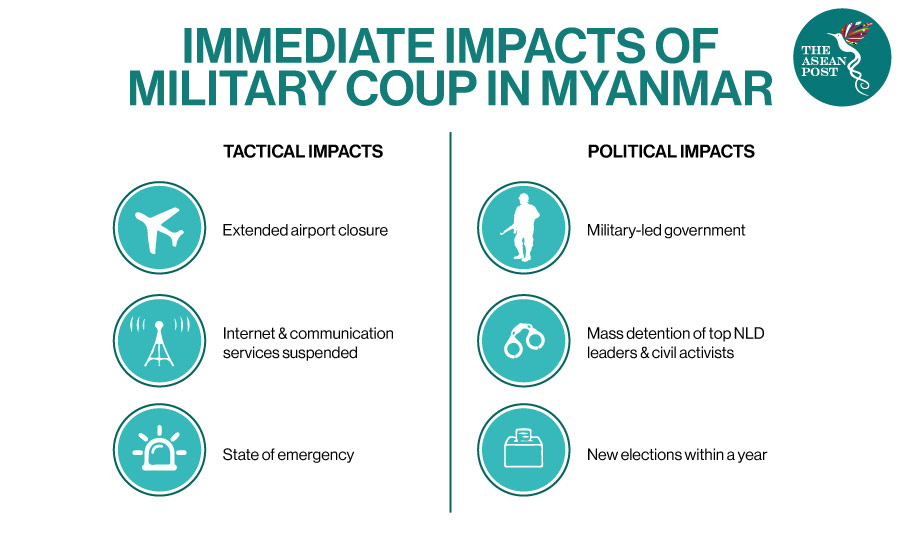

Arguably, following the 1 February coup, Myanmar generals appear to have sought to follow the Thailand model of military control.

That model suggests that militaries can successfully stage coups and guide democracy where strong central governments traditionally dominate. Things are made easier for the military when elected officials face a judiciary that sides with the armed forces, and civilians are more divided among themselves than security officials.

It is these instructive lessons which Myanmar’s military took from Thailand’s coups of 2006 and 2014. Following Thailand’s 2006 coup and enactment of a 2007 constitution which weakened civilian rule, Thailand witnessed six years of frail democracy.

From 2008 to 2014, elected Thai governments exerted little effective civilian control, invariably acquiescing to military preferences.

The feebleness of Thai democracy helped convince Myanmar’s military to enact its own 2008 constitution and hold elections in 2011. As in Thailand, post-2011 Myanmar governments exerted little control over the military, often deferring to it.

But Myanmar Was A Step Ahead

However, Myanmar’s military was a step ahead of Thailand. It controlled 25 percent of legislatures in each House of Parliament, enjoyed autonomy from civilian monitoring of its economic holdings and dominated the National Defence and Security Council.

Thailand’s 2017 constitution impressed Myanmar’s military leadership. Thailand’s Senate, Election Commission and Constitutional Court were appointed by the military government, a new electoral formula preventing parties from obtaining Lower House majorities, and governments now had to abide by a 20-Year National Strategy to ensure enormous funding for the military or potentially face impeachment.

Meanwhile, Palang Pracharat, a military proxy political party which utilised state resources, was created. Deputy Prime Minister (and retired General) Prawit Wongsuwan remains the party’s leader. The party has also employed local voter canvassing networks and offered welfare handouts to entice voters.

Learning from Thailand’s 2019 election and its use of a new constitution to entrench its position in politics, the Tatmadaw tried to modify the 2008 constitution to enhance military control.

But the National League for Democracy (NLD)-dominated Joint Parliamentary Committee for Constitutional Amendment vetoed these attempts.

It is no surprise that the Tatmadaw looked longingly at Thailand. If Myanmar’s military leaders could implement a charter similar to Thailand’s 2017 constitution, then their proxy Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) might finally win an election against the NLD, propelling the military to electorally dominate the state.

But Myanmar’s November 2020 election result delivered another super-majority to the NLD, guaranteeing that constitutional changes would not be implemented anytime soon.

In a way, like Thailand’s 2014 coup allowed Thailand’s military a few more years to fix the constitution, Myanmar’s 2021 take-over tries to do the same.

But Clear Differences Remain

There are differences between the Thai case and the situation in Myanmar.

First, Thailand has long been controlled by an arrangement between monarchy and military with the latter as junior partner. The military derives much power from the legitimacy it possesses as guardian of the monarchy, especially its closeness to the late Rama IX (beloved by most Thais).

His enormous popularity and endorsement of the 2006 and 2014 coups (amid Thai divisions regarding Premier Thaksin Shinawatra) left Thais divided but kept the balance skewed towards the military. On the contrary, Myanmar’s coup seemed to have provoked a massive domestic backlash.

Second, having influenced the writing of at least 15 constitutions, Thailand’s military has taken a long path in finally succeeding in engineering political party dominance and gaining national primacy. It has entrenched itself into the political system.

However, in Myanmar, the senior officer corps has long perceived itself as the “rescuer” of the country from colonialism and foreign enemies, ensuring its persevering and privileged national security role.

This viewpoint helped rationalise its 1962, 1988 and 2021 interventions. At the same time, Tatmadaw officers have become a privileged economic class – the most powerful nationwide.

But that sentiment is not shared by the general public. The country remains disunited, with few civilians enjoying popularity except for Aung San Suu Kyi.

Meanwhile, the military has been more successful at using brute force rather than constructing a successful political party. – CNA

Related Articles: