The military in Myanmar, also known as the Tatmadaw, is guaranteed 25 percent of parliamentary seats under the country’s constitution. If the National League of Democracy (NLD) - the party under Aung San Suu Kyi that won the general elections in 2015 - wants to implement any constitutional changes, it would need more than a 75 percent majority. This means that any effective change requires some approval from the army.

Thailand is currently under military rule until the country goes to the polls on 24 March. The hope is that after this election, Thais will be able to welcome democracy back. The question, however, is what kind of democracy will it be? Will it be democracy in its truest sense or one that worryingly resembles that of Myanmar’s?

The difference between Thailand and Myanmar is that Myanmar makes no attempt to hide its military’s convenient grip over the elected-government.

Always in danger

Late last year, the media was buzzing with news of another possible coup should Thailand return to democracy. The ruckus was caused by comments made by army chief General Apirat Kongsompong in October 2018, after a reporter asked him if he was prepared to launch another coup.

“If politics does not create riots, nothing will happen,” Apirat was quoted as saying, refusing to rule out the possibility.

In all fairness, since then, Apirat and even Deputy Prime Minister General Prawit Wongsuwan have attempted to shut down rumours of the possibility of another coup, saying that any such talk was nothing but fake news.

This, however, does not take away from Apirat’s initial comment that another coup, if needed, was a possibility. In a country that has seen so many coups in the past, the question that has often lingered on many political observers’ and analysts’ minds is: if another coup is always on the horizon, then is there real democracy in Thailand?

This question has not escaped the minds of ordinary Thais either, according to the results of a recent survey by Suan Dusit Rajabhat University, better known as the Suan Dusit Poll.

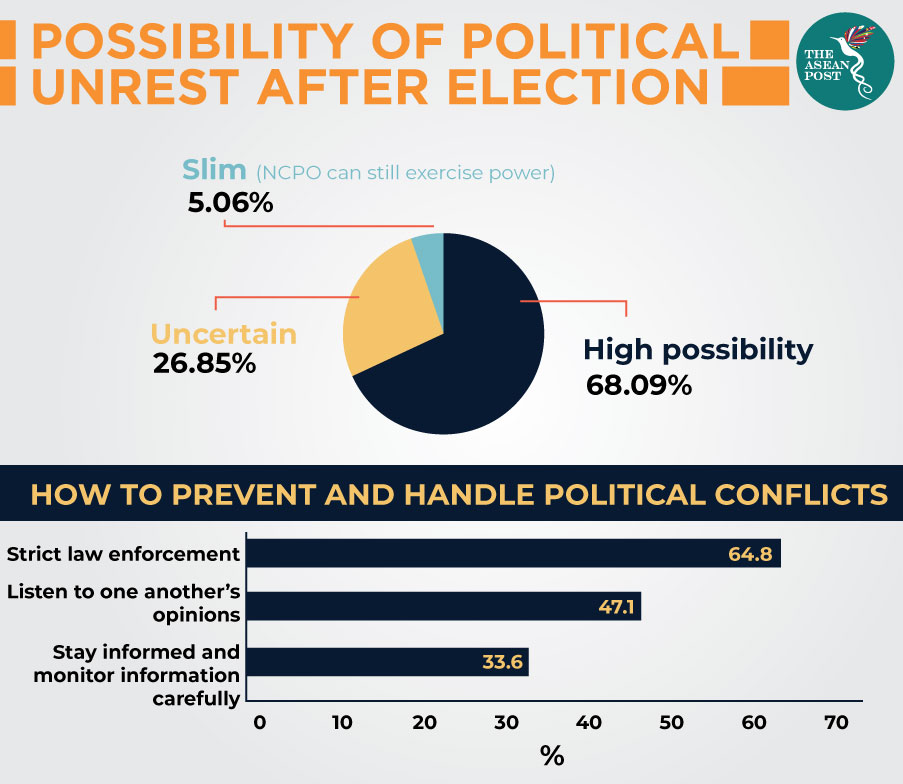

The poll, conducted between 26 February to 2 March, asked Thais whether political conflicts similar to those seen before the takeover of the country’s administration by the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO) are likely to return without effective preventive measures in place. 68.1 percent of respondents said the possibility is high; 26.9 percent were uncertain, saying that this would depend on the ability of the new prime minister in handling the situation; while 5.1 percent said the chance of political unrest returning is slim, as the NCPO still has abundant power under Section 44 of the interim constitution.

Section 44 states that the NCPO leader has absolute power to give any order deemed necessary to "strengthen public unity and harmony" or to prevent any act that undermines public peace.

Invisible grip on power

It is often argued that the ones with real power in Myanmar are the Tatmadaw. Based on the guaranteed 25 percent of parliamentary seats as described in the opening paragraph of this article, it’s easy to see why this argument exists.

The same thing, however, can be said about the political situation in Thailand. Today, military prime minister Prayut Chan-o-cha is running to legitimise his position as the country’s leader and he stands a fair chance at maintaining his position after the election. But even if he doesn’t, with another coup always looming on the horizon, it continues to be the military who maintains its invisible grip on power over the country.

Following Thailand’s latest coup in 2014, Paul Chambers, a professor at Chiang Mai University's Institute for South-East Asian Affairs, was quoted by international media as saying that there have been almost 30 coup attempts in Thailand (whether successful or not) since 1912.

Max Fisher, an American journalist based in Washington, United States (US) and columnist in the field of political science and social science, noted in an article back in December 2013 that Thailand has had more coups than any other country in the world.

Because Prayut is tied to the military, it wouldn’t be too far a stretch of the imagination to think that the military is indeed rooting for him. It is also likely that if Prayut wins, it will be status quo for Thailand.

On the other hand, even if Prayut loses and another politician takes his place as Thailand’s next prime minister, how long will it be before Thailand’s military says enough is enough and stages another coup to regain control of the government? And what does this new prime minister have to do to placate the military and prevent it from resorting to such measures? Who really has control over Thailand’s government?

Related articles: