Thailand made international headlines recently for detaining refugee footballer Hakeem Al-Araibi. Hakeem was a former Bahraini national youth player who was granted refugee status in Australia after fleeing charges in Bahrain connected to the Arab Spring protests. He was arrested at Bangkok’s main airport at Bahrain’s request in November last year when he arrived in Thailand for his honeymoon. He was released last Monday after Bahraini authorities decided to withdraw their extradition request.

Hakeem’s plight is not an anomaly. Thailand has long been notorious for its policy of not recognising and refusing to shelter asylum seekers and refugees; choosing instead to return them to their countries of origin.

Last month, Thai authorities intercepted 18-year-old Rahaf Mohammed’s attempt to seek asylum in Australia during her stopover in Bangkok. Rahaf, who was fleeing from her abusive family in Saudi Arabia, was intercepted by authorities during her layover in Bangkok and was made to prepare for deportation back to Saudi Arabia. Rahaf then barricaded herself in her hotel room, refusing to go back to Saudi Arabia, insisting her life would be in danger if she returned. After tweeting her plight to the world and garnering international support, Thailand made an exception and placed her in the care of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). She was later granted asylum in Canada.

The unlucky ones

Rahaf and Hakeem were fortunate enough to receive international support which resulted in their successful attempts in obtaining asylum. Unfortunately, many others like them are not as fortunate.

In May 2017, Thailand transferred Furkan Sokmen, a Turkish national with alleged links to exiled Turkish cleric Fethullah Gulen back to Turkey despite warnings by the United Nations (UN) that he would face abuse. In 2015, Thailand also reportedly returned approximately 100 alleged Uighurs –who are ethnically Turkic and a predominantly Muslim minority – back to China. Uighurs returned to China are known to face persecution.

Aside from deporting refugees, Thailand is also notorious in its mistreatment of refugees. The country is not a signatory to the UN convention on refugees which guarantees refugees certain rights and protections. Therefore, refugees who come to Thailand are considered stateless or irregular migrants and are not given any protection, do not have access to public services, cannot look for jobs and are often vulnerable to abuse.

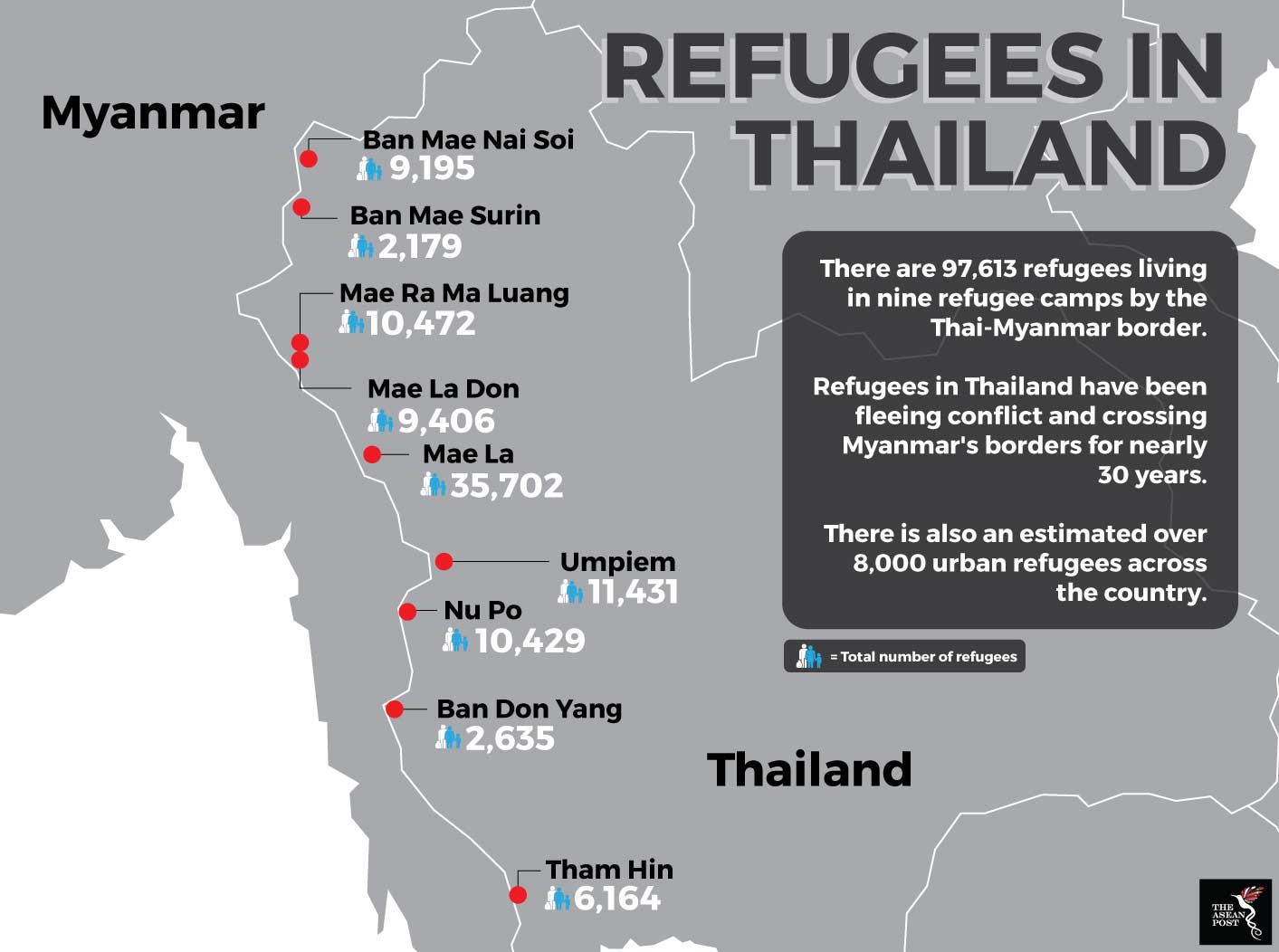

Currently, it is estimated that there are over 100,000 refugees in Thailand and most of them are from Myanmar. There are nine refugee camps along the Thai-Myanmar border and it is reported that many of the refugees there were born inside these camps and have never set foot outside.

According to Humanity and Inclusion, a humanitarian organisation, the living conditions in these camps are extremely poor. Drinking water is collected from wells and streams, and in the past, cases of cholera and malaria have been reported. Many children there also suffer from chronic malnutrition and respiratory infections.

Outside of these camps, data shows that there are over 3,800 urban refugees and 4,000 asylum seekers registered with the UNHCR in Thailand; 2,800 of which are children. Since no legal protection is afforded to them, these refugees are often mistreated by the authorities. When arrested they are often asked for bribes or threatened to be taken to police lock-ups or Immigration Detention Centres.

Source: UNHCR

Source: UNHCR

Children not spared

Thailand is also often criticised for detaining child refugees. In August last year, Thailand arrested 181 Vietnamese and Cambodian refugees and asylum seekers, 50 of whom were children. More recently, women and children refugees were among those arrested during the government’s harsh crackdown on illegal immigrants.

Over the years the government of Thailand has long promised to improve its treatment of refugees. In 2017, the government approved a framework to enhance identification and protection of refugees but nothing much has been heard of it since. A more promising development is the signing of a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) which acknowledges that children should only be detained as a measure of last resort and that the period of detention should be as brief as possible. While the MoU is a step in the right direction, human rights groups such as Fortify Rights and Human Rights Watch claim that the MoU does not address other key issues such as family separation and exorbitant bail charges for migrant mothers.

Many are sceptical of Thailand’s promises to improve the lives of its refugees, and they have every reason to feel that way. Until Thailand ratifies the UN convention on refugees, the jury there will continue to remain out.

Related articles:

How national laws propagate statelessness