Every year, an estimated 21 million girls between the ages of 15 and 19 years, as well as two million girls under the age of 15, become pregnant in developing countries. While the global adolescent birth rate has declined from 65 births for every 1,000 women in 1990, to 44 births per 1,000 women in 2018, the absolute number is still increasing and expected to continue growing due to the rising number of young people.

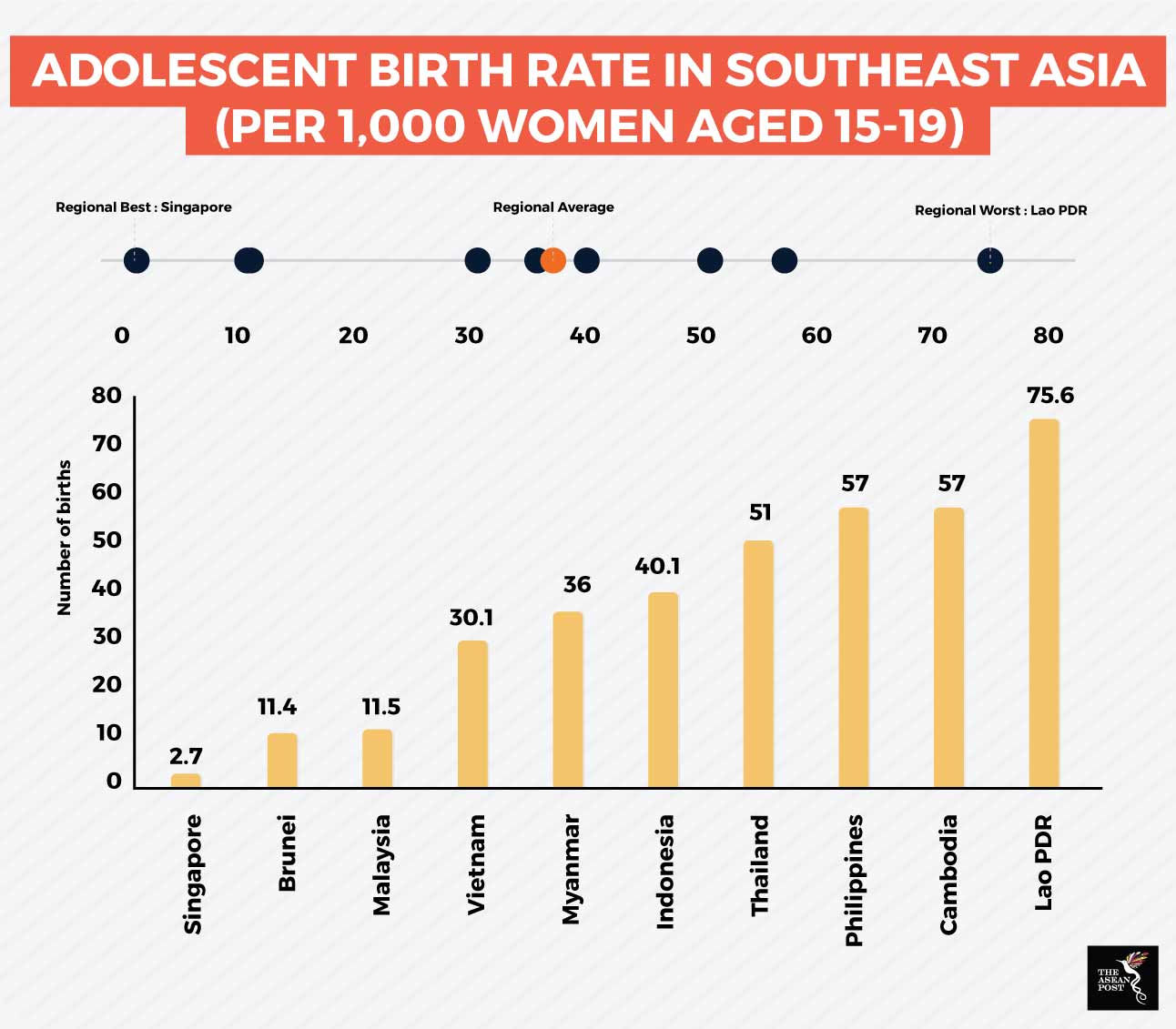

In the Southeast Asian region, the average adolescent birth rate in 2018 is 37.2 for every 1,000 women aged between 15 and 19. This is slightly lower than the global average of 44. However, the individual country rates show regional differences that point to different levels of development.

Singapore recorded the lowest adolescent birth rate for every 1,000 women aged 15 to 19 at 2.7, followed by Brunei at 11.4, Malaysia at 11.5, Vietnam at 30.1, Myanmar at 36, Indonesia at 40.1, Thailand at 51, and the Philippines and Cambodia at 57 each. Lao PDR recorded the highest adolescent birth rate in the region at 75.6.

Source: World Health Organisation

In Lao PDR, similar to the birth rate, the country also recorded one of the highest rates in the region for early marriages. A closer look finds that one in five adolescent girls drop out of school, one in four girls aged 15-19 are married, and from the same age group, one in 10 girls have begun childbearing. According to the country’s Voluntary National Review on the implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development both of these trends point to insufficient investment in developing their fullest possible potential.

The report, prepared by the government there, stressed that efforts towards improving investments in adolescent girls’ health, nutrition, and education is needed and will contribute towards gains in reducing early pregnancy, maternal mortality, and child stunting. Subsequently, this is hoped to translate into improved health and education outcomes for the girls. Building on their achievement in the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) - under which Lao PDR achieved a reduction to 83 per 1,000 live births - the country is now pressing forward with their focus on further reducing the adolescent birth rate.

Saving the mother, the baby and the future

Reduced adolescent fertility is included as one of the indicators for Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3: Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages, because it is an important measure to improve maternal health and to reduce infant mortality. It also addresses multiple factors that underpin attainment of robust sexual and reproductive health, gender equality, as well as adolescent social and economic well-being.

According to the United Nations (UN), there is substantial agreement that women who become pregnant and give birth very early in their reproductive lives are subject to higher risks of complications or even death during pregnancy and birth. Women who have children at an early age often have their education truncated as well, resulting in the curtailment of their opportunities for socio-economic improvement.

For children, being born to mothers who are too young puts them at a disadvantage. A study published by the medical journal The Lancet found that children of mothers aged 19 years or younger had an increased risk of low birthweight and preterm birth, stunting in infancy, short adult height, and poor schooling, and higher adult fasting glucose concentrations. While it is well-documented that adolescent pregnancies are more likely to be associated with these issues, as well as birth injuries, stillbirth, and infant mortality, the study found that the impacts extend into their adulthood, reducing their human capital key.

While children of mothers of advanced age are exposed to the same risks, the disadvantages were greatly reduced after adjustment for covariables, especially parity. The disadvantages of children of young mothers were independent of socioeconomic status, height, breastfeeding duration, and parity. Children of older mothers were also associated with distinct advantages for height and schooling.

Beyond the individual consequences, the cumulative impact of early pregnancy also weighs on the nation. Given the right environment, enabled and empowered young people, both male and female, are the fuel for the future of their countries’ development. When half of them are shackled, so is the nation in question.

Related articles:

Child brides: Unravelling the issues