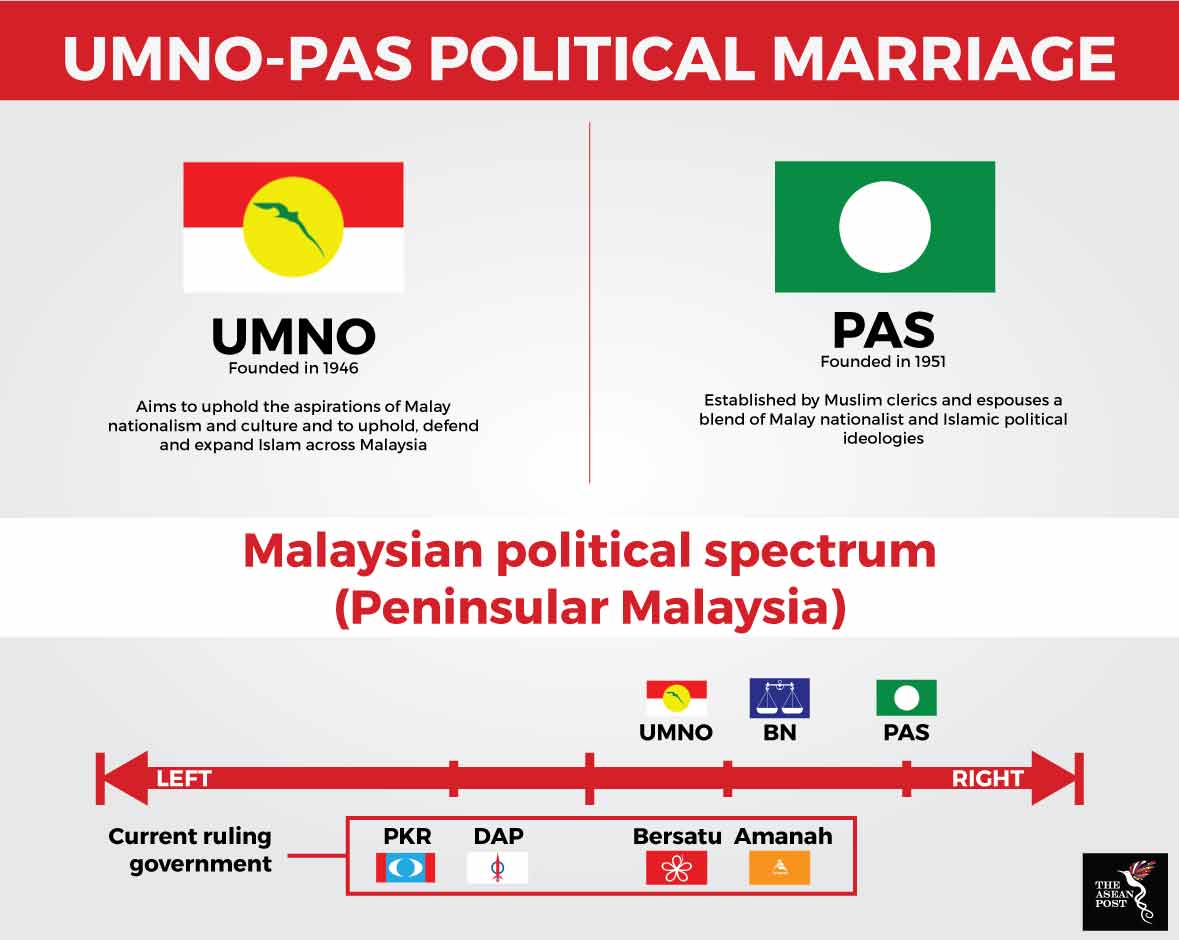

A recent rally celebrating the decision by the new government of Malaysia not to ratify the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD) marked the coming together of two major political parties in the nation’s political landscape – the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) and the Malaysian Islamic Party (Parti Islam Se-Malaysia or PAS).

There is an underlying political aspiration to this move of penyatuan ummah – or the unification of the Muslim community – in a country where race and religion have become permanent fixtures in politics. Under the guise of Malay bipartisanship, the rally was meant to serve as a reminder that though both parties may have stood on opposite sides before, they were willing to put their differences aside for the sake of Islam.

According to Yang Razali Kassim, Senior Fellow at Singapore-based S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies of Nanyang Technological University, the issue of Muslim unity is more critical to UMNO than PAS.

“For UMNO it is a matter of survival. UMNO is now under siege and could disintegrate anytime soon,” he said, adding that the move is a win-win for both, UMNO and PAS.

“So UMNO needs new support, a new lifeline. For PAS, unity is a strategy of political mobilisation.”

17 UMNO members of Parliament (MPs) hav since quit the party to become independents citing an alleged lack of direction in leadership. Local media reports have alleged that others may follow suit. The UMNO exodus has raised eyebrows as many of these MPs were once staunch supporters of the previous administration. Hence, the intentions of their move are now being heavily questioned.

Talks are also rife that some UMNO MPs and party members may switch allegiances to the government, under the Malaysian United Indigenous Party or BERSATU – a Malay nationalist party similar to UMNO that is chaired by Prime Minister Dr Mahathir Mohamad. The party was created after Dr Mahathir quit UMNO prior to the elections and joined forces with other opposition parties in a new coalition that swept to power in the 9 May general election. It now risks becoming a new version of UMNO if it accepts the very people it had previously vilified for corrupt conduct.

Source: Various

The moral argument of politicians jumping ship aside, UMNO’s loss of MPs has left it gasping for political space so the centre right party has seemingly moved further right to join PAS, a conservative Islamist party.

UMNO President, Ahmad Zahid Hamidi who has been pressured to go on garden leave after the mass UMNO exodus himself propositioned for an UMNO-PAS merger for the sake of the Malay race and Islam.

Yang Razali further explained that both sides are still unsure as to plans to close ranks in the name of Malay unity. “For example, within UMNO its president Ahmad Zahid Hamidi initially talked about a merger between the two parties. This was later contradicted by other top UMNO leaders including his deputy who said UMNO would not go so far,” he said.

“For PAS, their guiding principle behind unity is tahaluf siyasi – a form of political cooperation, nothing more.”

ICERD backtrack

The Malaysian government’s backtracking on its promise to ratify ICERD has become the clearest sign that it is starting to become sensitive to its Malay Muslim support base relative to UMNO and PAS. Moreover, the immense show of support by the Malays during the ICERD celebration rally is further proof of this point.

A Merdeka Center poll in August showed that Malay voter sentiments slid to below 50 percent for the first time since the euphoric electoral victory in May likely due to heightened use of racially and religiously fuelled rhetoric by the opposition.

However, Yang Razali opined that the new government there had already begun work finetuning its posture vis-à-vis the bumiputra – translated to “sons of the soil,” a term used to describe the Malay and indigenous population in Malaysia – voter base even before the issue of ICERD surfaced.

“You will recall that a national congress on the future of the bumiputras and the nation was held in September, marking the new government’s first step to re-engage the core issue of bumiputra empowerment,” he explained.

“It showed that the Alliance of Hope (Pakatan Harapan) acknowledged it must do something to strengthen its bumiputra voter base.”

Malaysia’s current political landscape is now seeing its government squaring off with the possible combined forces of UMNO and PAS as each scramble to consolidate their Malay voter bases. As Malays make up more than half of the nation’s population, having them on one’s side is paramount to ensuring future electoral victories.

Related articles:

ICERD non-ratification tarnishes Malaysia’s image

The road ahead for New Malaysia