The story of Malaysia’s general elections has been recounted numerous times by various local and international media outlets. Many of them rightfully highlighted the miraculous result – an unlikely victory by an alliance cobbled together three years before the country’s elections - led by two former political foes, Mahathir Mohamad and Anwar Ibrahim, defeating a coalition that has been in power for 60 years.

Most analysis of the elections would usually attribute the Alliance of Hope’s (Pakatan Harapan) victory (Pakatan Harapan) to Mahathir Mohamad’s return to politics. Experts have noted that his return to politics was a huge factor in swinging the Malay vote from then ruling party United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) to the component parties of the Alliance of Hope. While that may be true, many have discounted the role of the youth in ushering the Alliance of Hope to Putrajaya.

According to Malaysia’s Election Commission, millennials represented the largest voting bloc in the electoral roll. At the end of 2017, more than 40 percent of registered voters were aged between 21 and 39, which is more than double the number of voters over 60.

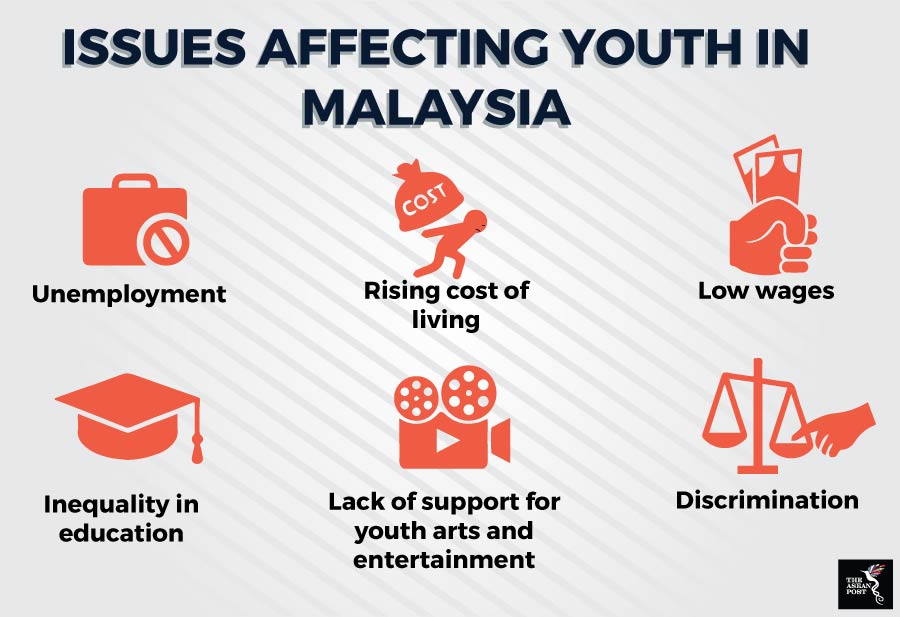

The millennials of Malaysia prior to the general elections had a long list of grievances with the country’s state of affairs. One of their chief concerns was the high rate of youth unemployment. In 2017, the country’s youth unemployment reached a record high of 10.8 percent which is three times higher than the overall national unemployment rate of 3.4 percent.

Unemployment compounded by an ever-rising cost of living had given birth to a generation disgruntled with the government. Furthermore, there were not many avenues for the youth to organize and get their voices heard as the Universities and University Colleges Act (UUCA) meant that university students could not get involved in politics.

Realising the massive voter bloc which the youth represented, the Alliance of Hope capitalised on it by creating various youth-friendly policies in its manifesto before the elections which later proved to be instrumental in its victory. Among them included abolishing the UUCA, promising one million jobs with a minimum salary of US$600 a month for youths, affordable housing and more.

Source: Various

Source: Various

Hopes fading

Now that the post-election euphoria has washed off, many have woken up to the sobering reality that things might not be too different for the youth of Malaysia under an Alliance of Hope government. Ever since coming into power, the new government claims that it has been focusing on improving the country’s financial position following former Prime Minister Najib Razak’s 1MDB scandal. However, many have argued that the government is only using that as an excuse to not execute the rest of its manifesto. So far, it has not made any progress with regards to special pledges for the youth highlighted in their election manifesto.

Newly minted Minister of Youth and Sport, 25-year-old Syed Saddiq has also been heavily criticised for being too focused on his image rather than doing actual work. In his first month as minister, Syed Saddiq came under fire from activists and youths on social media for not defending his then press officer, LGBT activist Numan Afifi. Numan Afifi resigned as Saddiq’s press officer after claiming that it was “impossible” to work with the government after the abuse he received because of his sexuality. Saddiq’s non-response to the issue was perceived as him throwing his peer under the bus in order not to alienate the more conservative section of his support base. However, it has certainly tarnished his image of the young reformer in government.

The Minister of Education, Dr Maszlee Malik has not been doing too well either. Despite promises that there would be zero government interference in universities, Dr Maszlee was appointed as president of the International Islamic University Malaysia (IIUM). He refused to resign despite fierce protests from student groups and activists. Students have long hoped that campuses would return to the golden age of the 70s where they were vibrant centres of activism and intellectual freedom, free from political interference. However, it looks like that day may never arrive under this government too.

With a government that looks more interested in rousing excitement from the young and capitalising on their energy for electoral gain but less so in empowering them, where do Malaysia’s youth go from here? Avenues for the youth to be represented or even be heard seems as narrow as it used to be with the UUCA still intact and a Parliament dominated by old men. This begs the question, where do the youth go to be heard?

It is no surprise that the #UndiRosak (a campaign calling for people to spoil their ballots) movement gained some traction among the youth in the run up to the general elections. A poll carried out in August 2017 reflected such sentiments, with 71 percent of Malaysian youths answering “No” to the question “Do you think you can influence government decisions?”.

The Malaysian cabinet recently announced that the voting age will be reduced to 18 years but that could be pointless if ultimately none of the parties want to genuinely represent the interest of the youth in Parliament.

The lack of avenues and platforms for the youth to influence the country is worrying, but even more worrying is what they could resort to if there are no legitimate avenues for them to effect change.

Related articles: