The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly changed the way people live their lives. One of the notable implications of the crisis is the sudden emergence of remote working for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and even major corporations. Following the virus lockdowns by governments worldwide, organisations have been forced to reconsider their standard operating procedures (SOPs), business strategies and cost structures.

Some companies are embracing work from home (WFH) as the new normal, potentially to be implemented for the long-haul, whereas some are not in favour of the arrangement as it’s not entirely suitable for all employees and business sectors.

Nevertheless, some observers claim that this new normal has exposed a drawback; work hours have stretched.

Pre-Pandemic

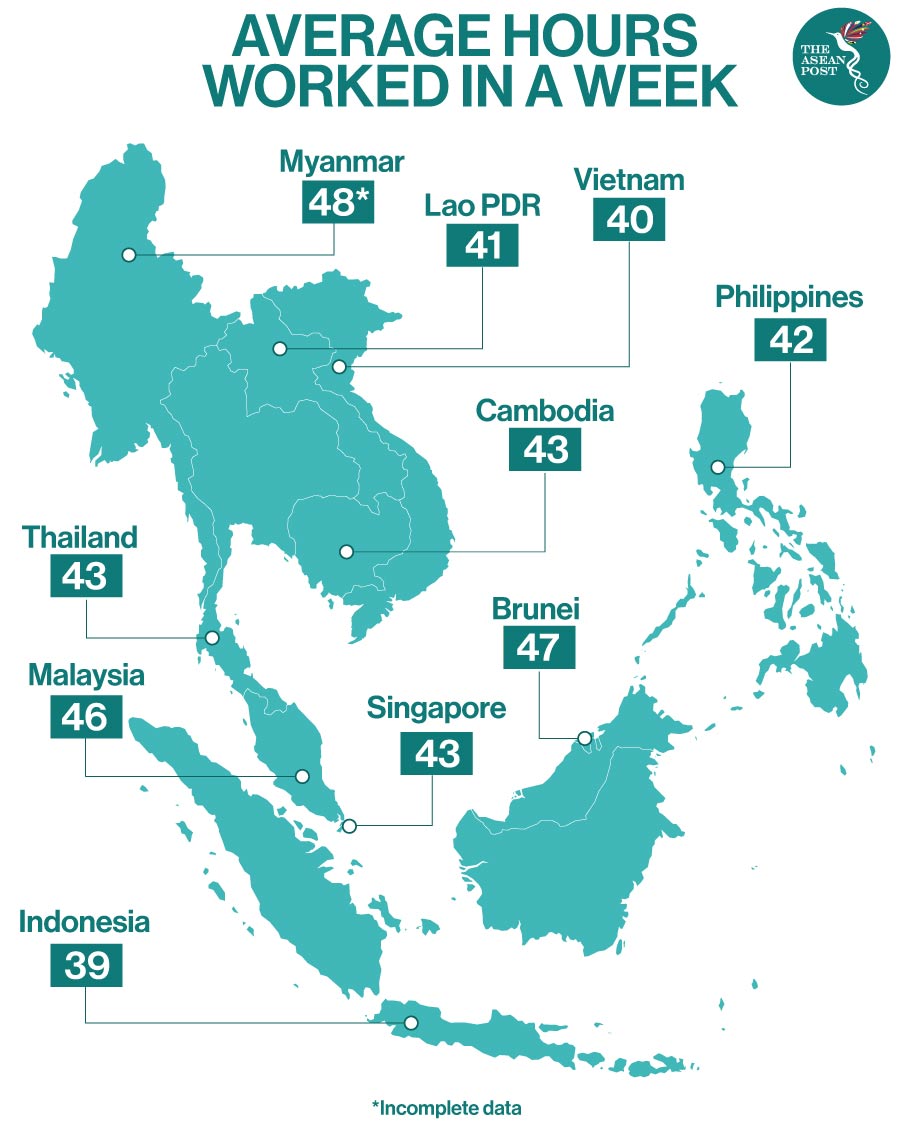

Although it is commonly accepted that productivity decreases as hours worked increases, three ASEAN countries rank in the top-10 of a list of countries where people work the most hours per week.

According to the International Labour Organisation (ILO), the top-10 countries in the list – of which nine are in Asia – all work at least 45 hours a week.

Qatar leads the way with the world’s longest average working week with 49 hours, while Myanmar are joint-second with Mongolia on 48 hours. Brunei is tied with Pakistan and Bangladesh on 47 hours while in Malaysia, like China and Mexico, employees spend an average of 46 hours a week at work. Two other ASEAN countries, Thailand and Singapore, are in the top-20 with an average of 43 hours spent at work each week.

However, how productive – or more importantly, efficient – these workers are is an entirely different story.

Historic Proof

The effects of long working hours on productivity, and quality of life, have long been documented.

More than a century ago, Ernst Abbe, the head of the Zeiss lens factory in Germany, observed how the shortening of working hours from nine to eight hours a day resulted in an increase in production.

Countless tests since then have shown that Abbe’s findings still hold true, and there is a point – usually at about 40-50 hours per week – after which total productive output will decrease as additional hours are worked.

In the 1920s automobile tycoon Henry Ford experimented with different work schedules for his employees. After introducing a five-day, 40-hour week in 1926, he discovered that his employees actually produced more in five days than they did in six.

Researchers from Stanford University in the United States (US) found that when employees are made to work longer than 40 to 50 hours per week, their total output over an extended period of time will drop below the level it had been when only 40- to 50-hour workweeks were required.

In other words, more work was actually shown to be detrimental to output.

As the researchers note, many managers seem to subscribe to the idea that in order to increase productive output, one need only increase the number of hours that employees work.

Taking A Toll

They explain that although employees may take an hour or two at the beginning of their work day to reach maximum efficiency, after maximum efficiency is reached, a slow decline in productivity is generally seen as additional hours pass.

“In this sense it is fair to say that many managers and companies believe that hours worked and output have a linear, or at least directly proportional, relationship with one another. This is almost certainly not the case,” they pointed out.

“The troubles with crunched work environments extend beyond the immediate realm of the office. Long hours and weekends ruined by stints at the office can take a harsh toll on marriages and families, as well as employees’ general psychological and physical health,” added the Stanford University website dedicated to a project on ethics and computer science.

Apart from taking a toll at home, an overworked employee might be so fatigued that any additional work he or she might try to perform would lead to mistakes and oversights that would take longer to fix than the additional hours worked.

The Stanford researchers pointed out that this sort of occurrence is clear and has been long-recognised in industrial labour; overworked employees using heavy machinery are more likely to injure themselves and to damage or otherwise ruin the goods they are working on.

In the case of the current pandemic, overworking and isolation could lead to increased stress, which could fuel physical problems such as metabolic issues, as well as mental health problems such as loneliness and depression.

It was reported that by early April this year, nearly half of workers in a survey of 1,001 US employees by Eagle Hill Consulting said that they were burnt out from WFH.

As the economy takes a hit and the prospect of layoffs looms – some workers have expressed gratitude in being employed by working extra hard. Nevertheless, it’s important to practice self-care amid a pandemic. Having enough time to rest and recuperate away from work is important for maintaining health and productivity.

Related Articles: