In recent months, there has been a lot of talk about the abuse of women and children amid the pandemic as many countries had imposed virus lockdowns. The Southeast Asian region is no exception. The ASEAN Post has published numerous articles on this topic as well as women empowerment and gender equality. But is there another side to the abuse coin?

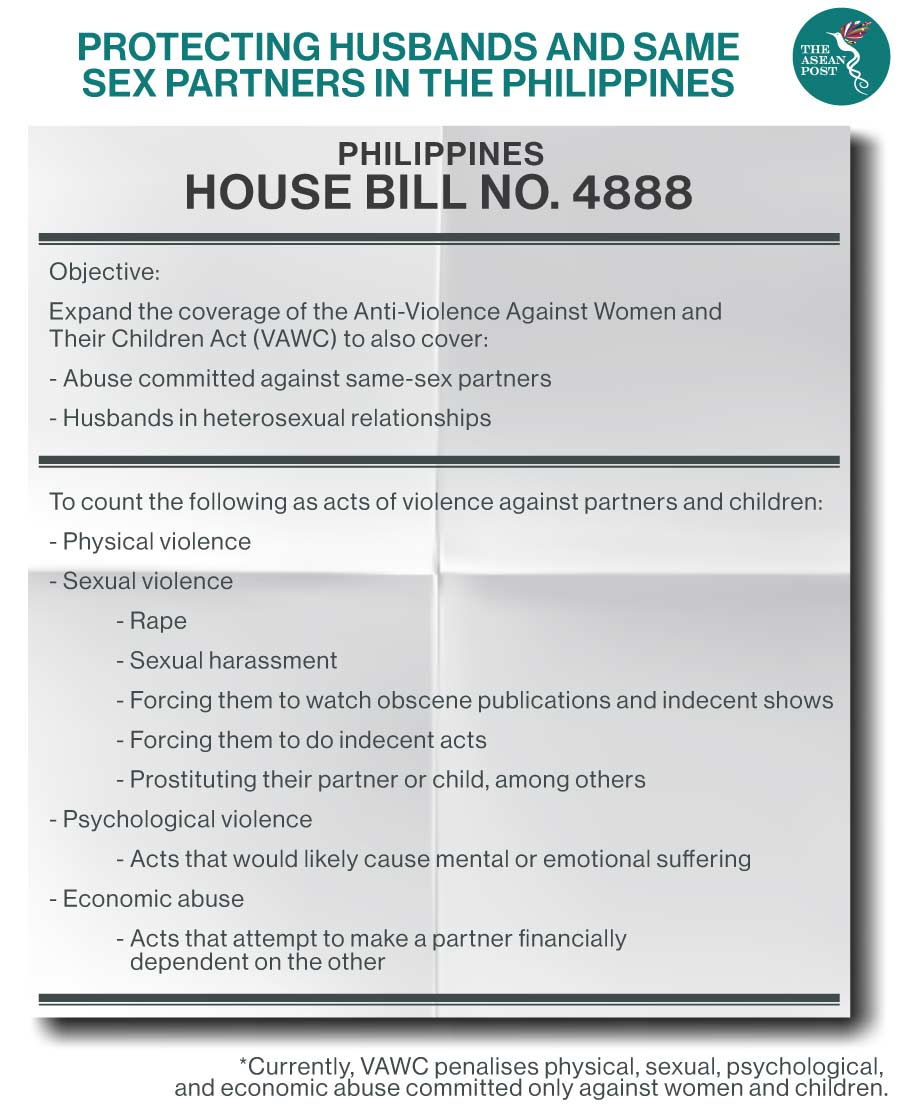

Last October, a lawmaker in the Philippines filed a bill that would protect spouses and partners in intimate relationships – regardless of gender – against domestic violence. The House Bill (HB) No. 4888, filed by Rizal 2nd District Representative, Fidel Nograles, seeks to expand the coverage of Republic Act (RA) No. 9262 or the Anti-Violence Against Women and Their Children Act (VAWC) of 2004 to also cover abuse committed against same-sex partners and husbands in heterosexual relationships.

Under the bill, the term "partner" covers not only heterosexual relationships, but also "lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer, intersex, cisgender, and transgender partners."

It is completely understandable that in a gay relationship between a man and a man, there is the possibility of abuse. But what of heterosexual relationships? How common is it for men to be abused by women?

In a publication written by Manila Doctors Hospital’s Rafael R Castillo, the medical doctor quotes anti-domestic abuse advocate Emiliano Manahan, also known as Nano, as saying that the incidence of male abuse is on the rise, affecting 12 to 15 out of every 100 couples in the country.

Castillo goes on to write that according to Nano, the problem is that the majority of men, who are victims of domestic abuse, don’t even see themselves as victims. They find it difficult to recognise abuse in their relationship, in contrast to women who have a high “index of awareness” for domestic abuse committed against them or their children.

“Of course, the macho ego also kicks in, preventing the men from admitting abuse. They just keep it to themselves,” Castillo writes.

Toxic Masculinity

In some societies, it is considered unmanly for a man to cry, because the male stereotype depicts men as being able to protect themselves. This toxic masculinity only makes it worse for men who have been abused. Men are generally afraid to come forward as victims for fear of being perceived as being weak.

Castillo mentions that Nano notes in his book the problem of male domestic abuse – which may not necessarily be physical, but can also be emotional, sexual or financial – has been trivialised and made the subject of jokes. The men are referred to as “under the saya (skirt),” “takusa” – short for “takot sa asawa” (afraid of wife), or suffering from “asthma” because they have to ask permission from their wife (“asma” or ask my wife) for everything they want to do, or every time they want to go out with the boys.

According to the Federation of Gender and Development (FGAD), while battered husbands do exist, one of the reasons they kept quiet was because of pride.

“They prefer to keep it confidential. Men have their pride too, and they do not want to come out publicly,” FGAD president Rene Estorpe was quoted as saying.

Is a law needed to protect husbands?

Going back to the question at hand “do we need HB No. 4888?” it is important to note that divorce is (at least currently) still not allowed within the country, except for Muslim Filipinos. A divorce law has been in the works for quite some time but as of today, only annulment of marriages are allowed for the majority of Filipinos who aren’t Muslim.

A divorce law would, of course, make it easier for battered husbands to get themselves out of the domestic abuse they’re facing at home. Nevertheless, it would seem that the law protecting women and children must still be amended.

According to the FGAD report mentioned earlier, another reason battered husbands choose to remain silent is because they fear that in the end it will be them who are sued. Ironically, the law that is protecting women and children is the same law that is victimising these battered husbands.

Estorpe cited the cases of two husbands in Agdao Centro, where he is the barangay (village) chairman, as examples of how men – who tried to complain about abuse by their wives – ended up being charged themselves. The two complaining husbands found themselves charged with violating the VAWC law.

“The wives accused them of engaging in illicit affairs,” Estorpe was quoted as saying.

Some women rights activists fear that speaking of abuse against men might steer the narrative away from the abuse of women and children. This is especially pertinent considering the fact that the two latter groups have suffered enormously throughout history. Nevertheless, the conversation surrounding violence against men needs to be amplified, so that victims can receive full support and aid without feeling shame or guilt.

Related Articles: