When the 34th ASEAN Summit concluded last month in Bangkok, Thailand, it came as no surprise that the bloc was met with heavy criticism for suggesting Rohingya refugees will repatriate back to Myanmar within two years.

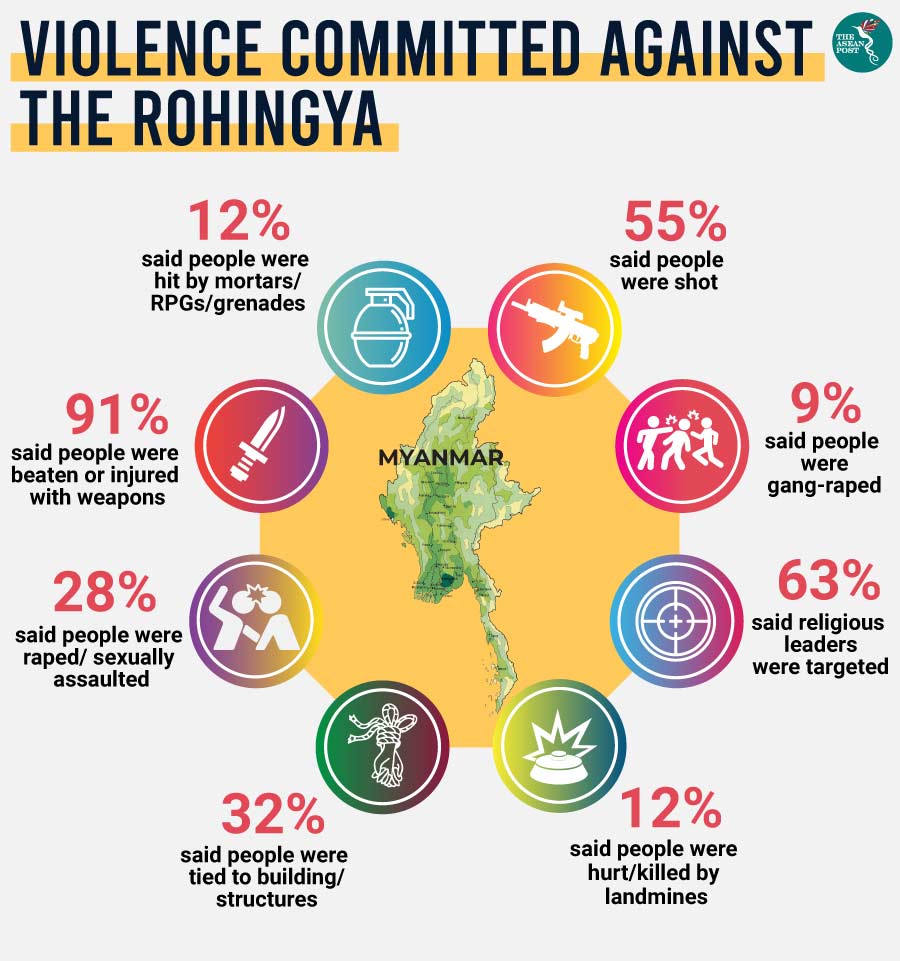

More than 700,000 Rohingya were forced to flee northern Rakhine state in western Myanmar during a 2017 military-led crackdown the United Nations (UN) has said included mass killings and gang-rapes executed with “genocidal intent”. Almost 400 Rohingya villages were burned to the ground during the violence.

A final statement from the weekend summit said ASEAN leaders supported Myanmar’s efforts to “facilitate the voluntary return of displaced persons in a safe, secure and dignified manner”. The statement did not even include the term Rohingya.

The criticism ASEAN faced in relation to the way it has been handling the Rohingya issue is nothing new. Human rights observers have often claimed that the 10-member bloc has done little to ensure the safety of the Rohingya, asserting that diplomacy between member countries, as well as its adherence to a non-interference policy, has consistently trumped human rights concerns.

The Rohingya themselves have been largely against the idea of returning, citing safety concerns and a lack of citizenship.

If ASEAN is most concerned about repatriation then more bad news for the bloc surfaced recently when an Australian think-tank claimed that Myanmar has made “minimal” preparations for the return of Rohingya refugees sheltering in Bangladesh.

A report by ASEAN’s disaster management unit had praised the country’s efforts to ensure “smooth and orderly” returns. Meanwhile, Myanmar has repeatedly said it is ready to take back refugees and has often blamed Bangladesh for failed efforts to kick-start returns.

However, the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) said in a report that analysis of satellite imagery shows “no sign of reconstruction” in the overwhelming majority of former Rohingya settlements. On top of this, according to ASPI, in some areas, destruction of residential buildings has continued.

“The continued destruction of residential areas across 2018 and 2019 – clearly identifiable through our longitudinal satellite analysis – raises serious questions about the willingness of the Myanmar government to facilitate a safe and dignified repatriation process,” said Nathan Ruser, one of the researchers at ASPI’s International Cyber Policy Centre, in a statement.

Diplomacy versus human rights

As mentioned earlier, human rights observers have often accused ASEAN of prioritising diplomacy over human rights concerns. One such human rights group, the Human Rights Watch (HRW), had accused ASEAN of taking the Rohingya crisis lightly during the 2018 summit, saying that it focused largely on repatriation issues, treating the “humanitarian situation” in Myanmar’s Rakhine State merely as “a matter of concern” while disregarding the Myanmar government’s crimes against humanity.

Prior to the 2019 Summit last month, HRW urged leaders of ASEAN to “drastically rethink their response” to the plight of the Rohingya. This was especially in the face of the 56-page leaked report which, according to the rights group, was developed without input from Rohingya refugees and “almost entirely” disregards the Myanmar government’s atrocities that led to mass displacement.

“ASEAN seems intent on discussing the future of the Rohingya without condemning – or even acknowledging – the Myanmar military’s ethnic cleansing campaign against them. It’s preposterous for ASEAN leaders to be discussing the repatriation of a traumatised population into the hands of the security forces who killed, raped, and robbed them,” said Brad Adams, executive director of HRW’s Asia Division.

Following the 2019 Summit, Malaysia in particular made strong statements on the Rohingya crisis. Its Prime Minister Dr Mahathir Mohamad asked for International monitoring bodies to ensure that Rohingya refugees who return to Myanmar are not exposed to any danger.

Unfortunately for the Rohingya, for more than 50 years, ASEAN’s non-interference principles have only been grossly contravened twice: once in 1986, when the bloc called for a peaceful resolution to political upheaval in the Philippines amidst the People Power Revolution, and again in 1997 when dealing with the admission of Cambodia into the association following a coup by its current Prime Minister, Hun Sen.

It is understandable that ASEAN wants to keep good diplomacy between all its members but a line must be drawn. If it is indeed true that Myanmar has made no preparations for the return of the Rohingya but claims that it is ready to take the refugees back then something is amiss. ASEAN must assume the worst in this case and act accordingly, otherwise it will be responsible for whatever atrocities might befall the Rohingya after repatriation.

Related articles: