Every time Malaysia’s national oil and gas company PETRONAS declares a profit, the nation’s four oil-producing states will clamour for a bigger slice of the pie than the current five percent royalty they are receiving.

The subject rose again following the unexpected victory of the Alliance of Hope (Pakatan Harapan) in the country’s May 2018 general election, ending the 61-year continuous rule of the National Front (Barisan Nasional). As part of its election manifesto, the Alliance of Hope coalition promised to increase the oil royalty to 20 percent and to review Malaysia’s Petroleum Development Act of 1974 (PDA) if it came into power.

Prime Minister Dr Mahathir Mohamad announced that the new government of Malaysia will pay the oil-producing states 20 percent but it will be calculated based on profits derived from those states, and not revenue.

“The precise definition of the 20 percent royalty will have big implications on the finances of PETRONAS, federal and state governments,” said Suhaimi Ilias, Group Chief Economist at Maybank Investment Bank.

If royalty is levied on revenue, it will be a fourfold increase over what these states currently enjoy. However, if the royalty is levied on profit, the increase in royalty payment will be much less, he added.

“There is also the issue of what ‘profits’ will be used for the 20 percent calculation. Is it PETRONAS Group’s total profits or just profits from PETRONAS’ upstream operations?” he asked.

Royalty not specified

The PDA does not explicitly spell out the quantum of royalty.

When the PDA was constituted, there were existing concessions given to Shell, Exxon (now ExxonMobil), Esso and Continental Oil to explore and extract oil in territories that make up Malaysia today. These were renegotiated into production sharing contracts (PSC) which outlined revenue sharing.

Generally, 10 percent is allocated for royalty, to be shared equally by the states and federal government; 70 percent goes towards cost recovery; and the remainder is divided between PETRONAS and the PSCs who also have to pay petroleum income tax.

A 15-percent royalty increase will shrink PETRONAS’ slice of the pie. This will impact either its dividend payment to the federal government or its ability to invest further in upstream activities.

The federal government received US$3.9 billion in dividends for 2017 and PETRONAS said it would allocate US$5.8 billion for dividends this year. The funds will help cover a shortfall in federal revenue after the new government abolished the unpopular goods and services tax (GST) in August.

On the other hand, PETRONAS requires capital expenditure (capex) for upstream development to remain viable long-term. It has been cutting its capex spending since 2013 and even laid off staff due to lower oil prices. PETRONAS only raised its capex spending to “around US$13.4 billion” this year following an improvement in global oil prices.

“An increased share of royalty would squeeze the level of net profit available to all investors and potentially put new oil and gas investment at risk,” said Andrew Harwood, Wood Mackenzie’s research director.

Sharing an increased portion of PETRONAS’ net profits with Sabah and Sarawak would have the “least impact on other investors,” he said. “Investors value stability when making multi-million or multi-billion-dollar investments. The best solution would be one that limits uncertainty and does not impact the considerable investment required by Malaysia’s oil and gas industry.”

Source: Various sources

Resource-rich country

Malaysia was formed in 1963 as a federation comprising Malaya and Singapore (which left in 1965) in the Malay Peninsula, and Sabah and Sarawak in northern Borneo. Each state is governed by a Chief Minister and its own legislative assembly.

The South China Sea which separates the peninsula and Borneo is rich in natural resources. Oil was discovered in Miri, Sarawak back in 1910.

In 1971, a spike in global oil prices led Sarawak’s Chief Minister, Abdul Rahman Ya’kub, to propose establishing a state-owned oil company. However, his nephew Abdul Taib Mahmud, who was then the federal Land and Mines Minister wanted to create a federal statutory body to assume total rights over all of Malaysia’s oil and gas resources.

After Abdul Rahman rejected this proposal federal Finance Minister Tengku Razaleigh Hamzah proposed forming a company instead, to distribute profits between the federal and state governments. The five percent royalty was agreed upon.

Thus, Petroliam Nasional Berhad or PETRONAS was formed in 1974 under the PDA. Tasked with developing the nation’s oil and gas resources, it grew to become the country’s only Fortune 500 corporation with operations abroad.

Abdul Taib later became Sarawak’s Chief Minister in March 1981 and remained in power until February 2014. During this time, there was no demand for additional royalty from oil. Both Sabah and Sarawak were rich in timber resources, which was easier to extract than offshore oil.

Nonetheless, development in Borneo was slower than on the Peninsula and dissatisfaction grew over the distribution of the nation’s oil wealth. Abdul Taib’s successor Adenan Satem was more vocal in demanding a higher royalty payment and for “Sarawak rights.”

The Sarawak ‘rebellion’

PETRONAS trimmed its workforce by as many as 1,000 in 2016. The Sarawak government insisted that Sarawakian employees working in the state be the last to be laid off. To force its case, it froze the work permits of non-Sarawakian PETRONAS staff.

Adenan died the following year. His successor Abang Abdul Rahman Zohari continued Sarawak’s autonomy agenda. He set up Petroleum Sarawak Berhad or PETROS as the state’s version of PETRONAS, based on a pre-Malaysia law, the Oil Mining Ordinance 1958 (OMO).

However, despite its lofty aspirations, it is not feasible for PETROS to duplicate PETRONAS’ infrastructure. The latter has already made significant investments throughout the country, including Malaysia LNG (MLNG) the country’s largest liquefied natural gas (LNG) manufacturing complex in Bintulu, Sarawak.

Sarawak’s challenge to the PDA has opened up a Pandora’s Box. The Chief Ministers of both Sabah and Sarawak signed over their respective states’ oil rights without getting the approval of their legislative assemblies, raising further questions on the PDA’s validity.

Furthermore, the PDA was enacted while Malaysia was officially in a state of emergency following the racial riots of May 1969. During this time, each state’s territorial waters were limited to three nautical miles from shore. Oil and gas found further at sea belonged to the federal government.

The emergency declaration was officially lifted in 2011. Sarawak argues that laws passed during an emergency cease to be in force once the emergency is lifted.

Realising this, the federal government pushed through the Malaysia Territorial Sea Act 2012 to retain the same three-nautical-mile boundary. Ironically, Sabah and Sarawak were part of the National Front coalition that voted in favour of this Act.

The present federal government said that the PDA will be reviewed, to provide for a revision of royalty payments. The outcome remains unclear on who has ownership of Malaysia’s oil and gas resources. If the states regain that right, PETRONAS may be forced to evolve into an international oil company like Shell, BP or ExxonMobil, and deal with the oil-producing states through PSCs and negotiate revenue sharing on a case-by-case basis.

Related articles:

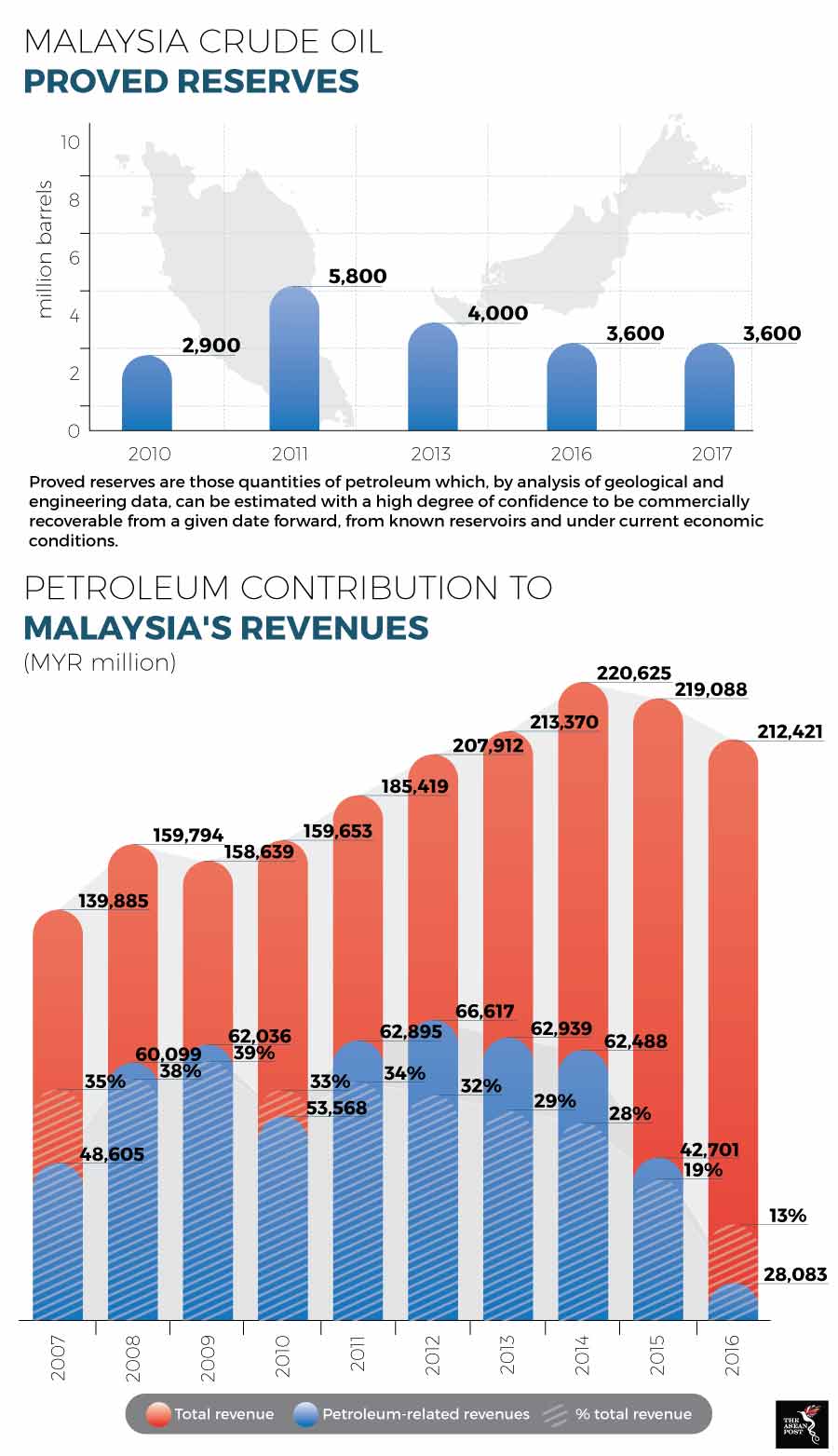

Petroleum's contribution to ASEAN sustainability