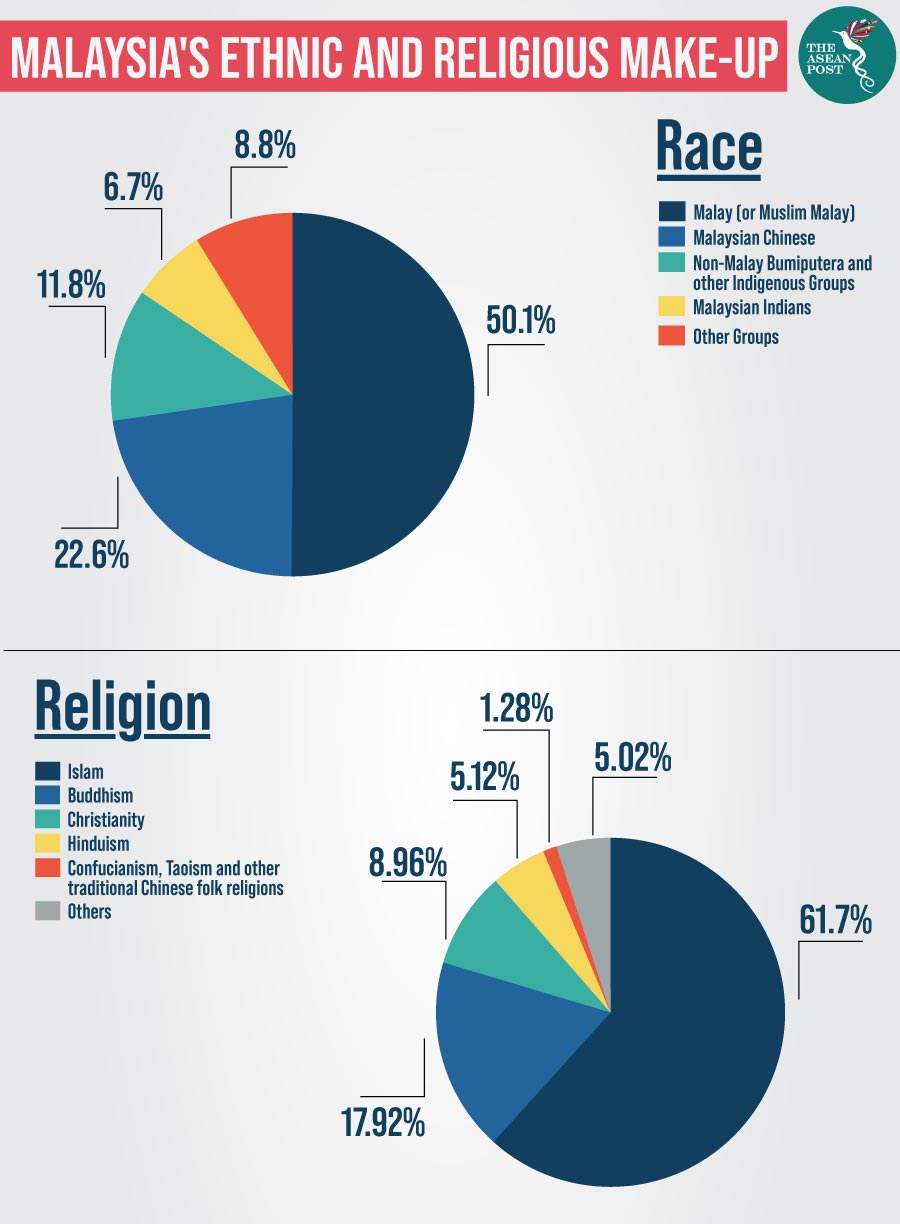

Malaysia is a Southeast Asian country where a multitude of ethnicities and people of varying religious beliefs call home. While Malay Muslims make up a large majority of Malaysians, non-Muslims and non-Malays have been able to co-exist with their Malay Muslim counterparts with relative ease. This peace, however, has not come without its own tests and over the years there have been black spots in Malaysia’s history. One that is often cited is the 13 May 1969 incident, which refers to the Sino-Malay sectarian violence which happened in Kuala Lumpur.

In more recent times, however, this unity among the races and people of differing religious beliefs has been put to the test by the appearance of one individual. A man who – aside from possessing permanent residence (PR) in the country – was neither born nor raised in Malaysia. That man is none other than the internationally famous (or infamous), controversial Muslim preacher from India, Zakir Naik.

Two years ago, in 2017, Naik moved to Malaysia while on the run from Indian authorities who were mulling terror charges against him. It is worth noting that this was before Malaysia’s 2018 general election (GE14) which saw a historic and peaceful change of government. It has since been revealed that Naik was granted a Malaysian PR in 2015.

Even back in 2017, his presence did not sit easy with the non-Muslims of the country. 19 human rights activists (both Muslims and non-Muslims), including Hindu Rights Action Force chairman P. Waytha Moorthy, sued the Malaysian government for harbouring the man. Despite this, the government there continued debating against deporting Naik back to India – a debate that continued even into the new government’s administration under Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad.

Today, however, the government finally seems to have budged in favour of complaints which have largely (though not completely) been coming from the non-Malay, non-Muslim citizens in the country. The catalyst for this change was when Naik allegedly started getting himself involved in race-politics.

The accusation was based on a recent speech where Naik had spoken out against Malaysia’s two minorities: the Malaysian Chinese and Malaysian Indians.

On 8 August, Naik made a speech in Kota Bharu, capital city of the Northern state of Kelantan, claiming that Malaysian Indians are more loyal to Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi than to Prime Minister Dr Mahathir. At the same venue and in the face of calls for deportation by multiple parties, Naik called on Malaysian Chinese to “go back” first as they were “old guests” of the country.

Since that fateful speech, Naik has been investigated by Malaysian authorities, ministers have criticised his comments, and he has even been banned from speaking in seven of Malaysia’s 13 states. Prime Minister Dr Mahathir has joined his ministers in criticising what is now being viewed as “hate speech”. Previously, the Malaysian premier had said his government could not accede to calls to expel Naik, a Mumbai native, back to his home country of India as he would be “killed” there.

Malaysia's police have imposed a country-wide ban on "all activities" linked to the controversial Indian preacher for security reasons.

Deportation versus human rights

Dr Mahathir, however, may have made a valid point when he previously said that he could not send Naik back to India.

In August 2019, a news report from a local online news portal in Malaysia quoted the head of a government agency in India tasked with protecting religious minorities as saying that while he agrees Naik’s speeches could be offensive to Indians, the controversial preacher had reasonable grounds to fear persecution and unfair trial under the Narendra Modi government.

Zafarul-Islam Khan, a prominent activist who chairs the federal-backed Delhi Minorities Commission – an agency which safeguards the rights of Muslims, Christians, Sikhs, Buddhists and Parsis – also said that he believed the recent money laundering charges are part of a larger campaign by extremist Hindu forces to silence Naik.

“The Hindutva forces have had unbridled power since Modi came to power in May 2014. They are misusing it against their opponents, real or imaginary,” the news portal quoted Khan as saying.

In 2012, authors Erika De Wet and Jure Vidmar published a book entitled “Hierarchy in International Law: The Place of Human Rights”. In that book, they mention that “a requested state will be confronted with conflicting obligations stemming from extradition treaties and treaties on human rights, whenever the applicant faces a real risk that his or her fundamental rights will be violated by the requesting state.”

Nonetheless, Naik seemed to have presented his own solution to the problem back in 2017 in an interview aired on Saudi Arabian channel Al Majd TV. In the interview Naik boasted that “by God’s grace, I have been offered citizenship by at least 10 Islamic nations.” In the same year, it was revealed that Saudi Arabia had granted citizenship to the preacher.

Why did Malaysia “adopt” Naik?

The question that still remains is why has the government of Malaysia been adamant about keeping Naik in the country right up to his slip up at the Kota Bharu speech?

In March, the Malaysian authorities deported six Egyptians and a Tunisian despite outcry from human rights groups who said they would be tortured. This is not the only time Malaysia has deported people. Earlier, in 2016, Malaysia deported private school teacher Alettin Duman over charges that he was involved in a failed military coup in Turkey that year. Months later, in May 2017, three Turkish nationals wanted by Ankara for alleged links to a US-based preacher accused of being behind a failed coup against President Recep Tayyip Erdogan were also deported.

In April 2018, Swedish human rights group, the Stockholm Center for Freedom (SCF), said Duman was beaten, tortured and threatened with staged executions.

On top of the fact that Malaysia had no qualms about deporting people before, the country is also not a signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention.

Yet, for some reason - and despite outcry from Malaysia’s minorities and a call from the Indian government for him to be deported - when it comes to Naik, Malaysia is reluctant to send him back. Why? Find out in tomorrow’s article.

Related articles: