Although widespread in industries from aerospace to waste management, Artificial Intelligence (AI), machine learning and big data are cutting-edge technologies not usually associated with the legal profession.

Long considered a conservative profession, the legal trade is undergoing a shift thanks to Fourth Industrial Revolution technologies with AI an increasingly important tool in a law firm’s kit.

With the Chief Justices of Malaysia and Singapore talking about increased AI use in their respective addresses at the opening of Legal Year 2019, it is evident that technology has long-term benefits in both, law firms and court rooms alike.

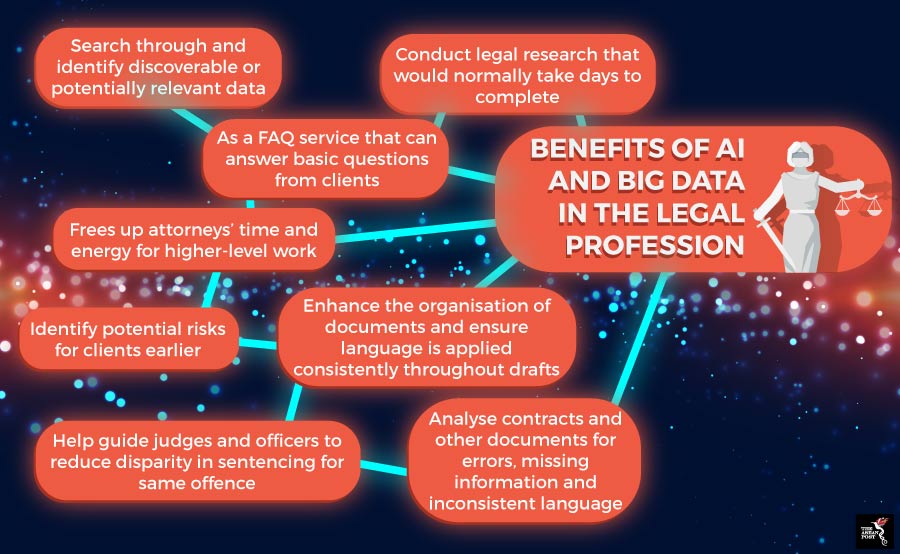

AI is increasingly seen as being able to complete monotonous legal work such as proofreading, research, preliminary document review or due diligence. Contract preparation and management are repetitive and tedious tasks which AI has proven to shine in.

With the ability to understand documents much faster than humans, AI frees up more time for lawyers to tackle tasks which require analytical thinking. This allows them to spend more time with their clients discussing strategies or other matters related to their cases.

In addition, AI’s processing capabilities combined with big data has made for AI-driven data analysis which can predict case outcomes.

Implementation in ASEAN

Malaysia’s Chief Justice Tan Sri Richard Malanjum extolled the virtues of AI during the opening of Malaysia’s Legal Year 2019 in January when he said judges in Malaysia will soon introduce AI to help decide on punishments for convicted criminals.

Malanjum revealed that the government of Malaysia was exploring a data-driven feature called “data sentencing” which helps judges achieve consistency when sentencing different offenders for the same crime.

Some states in the United States (US) already use such programs. One such program called COMPAS is a risk assessment algorithm which uses various data to create an assessment score for recidivism which judges may consider during sentencing.

Malanjum’s counterpart in Singapore, Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon noted that AI, data analytics and quantum computing have started to make machine-assisted court adjudication a reality but warned that it raised several issues.

“… the use of AI within a justice system gives rise to a unique set of ethical concerns, including those relating to credibility, transparency and accountability,” he said during his speech at the opening of Singapore’s Legal Year 2019 in January.

“For instance, recent studies have raised issues about bias in AI decision-making, and this has contributed to a spirited debate over the involvement of AI in the making of judicial decisions. Robust and rigorous discussions must be had about the proper use of such systems, and the way in which the undoubted potential of AI can be harnessed while its concomitant risks are managed.”

Despite these concerns, Singaporean law firms have been early adopters of AI.

In September 2017, Singapore law firm, WongPartnership became the first in the country to adopt artificial AI, using it to enhance its due diligence processes for Merger & Acquisition (M&A) transactions as part of the firm’s strategy to leverage on technology.

The firm teamed up with Luminance, a London-based company with customers in five continents and offers software which has been trained by legal experts and mathematicians from Cambridge University.

Using advanced machine learning techniques to automatically sort, cluster and classify data, Luminance’s AI can pinpoint even subtle differences between contracts so that hidden risks can be uncovered early on in a transaction, stated WongPartnership on its website. The platform’s ability to detect patterns across large volumes of contracts ensures that lawyers can focus their review on key documents from the outset.

“Technology is changing the way law is practiced and as such technological innovation must be a cornerstone of our firm’s future growth,” said Ng Wai King, Managing Partner at WongPartnership in a press release on the company’s website.

Last May, Thai firm Weerawong, Chinnavat & Partners became the first law firm in the country to use AI, and a month later, Indonesia’s UMBRA became the country’s pioneering law firm to use the technology. Both opted for Luminance’s services.

A case in point

In February 2018, AI contract review platform LawGeex beat 20 US-trained top corporate lawyers at identifying risks in Non-Disclosure Agreements (NDAs), one of the most common legal agreements used in business.

The highest performing lawyer in the study achieved 94 percent accuracy – matching the AI – while the lowest performing lawyer achieved an average accuracy of 67 percent. More tellingly, the challenge took the LawGeex AI 26 seconds to complete, compared to an average of 92 minutes for the lawyers. The longest time taken by a lawyer to complete the test was 156 minutes and the shortest time was 51 minutes.

There are concerns that AI could replace legal professionals, but the more realistic outcome is that it will complement the global legal services market which employed 6.9 million legal professionals in 2017 and was worth about US$633 billion according to business information publisher, MarketLine.

Although some jobs which require manual data entry or scanning of documents may be replaced by AI, there is no substitute for a lawyer’s experience and professional expertise.

Related articles:

Is the ASEAN workforce ready for the 4th Industrial Revolution?

Slow justice as Philippine drug war intensifies

Regulating artificial intelligence adoption in Southeast Asia