With increased digitisation of services these days it was only a matter of time before digital payments caught up. Digital payments are transactions of monetary value conducted via electronic means. These are expected to bring in US$32 billion in revenue to Southeast Asia by 2021, according to Euromonitor.

To capitalise on it, Ant Financial’s Alipay and Tencent’s WeChat entered the market with an initial focus on Chinese tourists to the region. Chinese tourists made 62 million outbound trips to Southeast Asia within the first half of 2017 alone.

Alipay’s parent company Ant Financial in 2016 partnered Thailand’s Kasikorn Bank to facilitate payments from Chinese tourists in yuan. Similarly, in 2017, it partnered with Fave to cater to Chinese tourists in Singapore. Around 1.1 million Chinese tourists entered Singapore within the first quarter of 2017 alone.

Alipay faced barriers at first in handling local currency transactions because local governmental approvals took time. It however has also since expanded into partnerships with Malaysia’s smartcard provider, Touch n’ Go (TNG) to reach 18 million TNG local users and partnered with Cambodia’s PiPay to reach the Cambodian market.

The question is, will this necessarily foster local adoption?

Local digital payments platforms know that they have the edge of knowing their markets better. But they have had to act fast in order to take advantage of that edge.

Southeast Asia’s unbanked population is a key market, but in order to effectively reach them, local e-wallets will need to leverage on data amassed through transactions over a period of time. Some providers may be able to form partnerships in order to leverage their data. GrabPay by Grab for instance, did that in Indonesia by partnering with e-money transfer firm Ovo.

In fact, GrabPay is already moving fast. Since expanding its service beyond in-app functionality in November 2017, it has also secured the appointment of Ooi Huey Tyng as managing director to help develop strategic partnerships across Malaysia, Singapore and Philippines. It also recently acquired Indian payments startup, iKaaz, to improve its technology.

Cambodia’s PiPay, meanwhile, aims for a market of 1,700 small merchants and has formed partnerships with various vendors to offer attractive discounts. Using QR codes as its modus operandi, it has managed to amass 190,000 user downloads, 80% of whom are Cambodian.

WeChat was recently granted approval in Malaysia to operate its e-wallet, WeChat Pay here. This would possibly allow it to introduce the rest of its WeChat services here including online shopping, money transfers, booking healthcare appointments. For WeChat, adoption is likely to be easier because they already have 20 million users of its chat messaging platform there, a Tencent official told Reuters in November 2017. Worldwide, it has 980 million active monthly users.

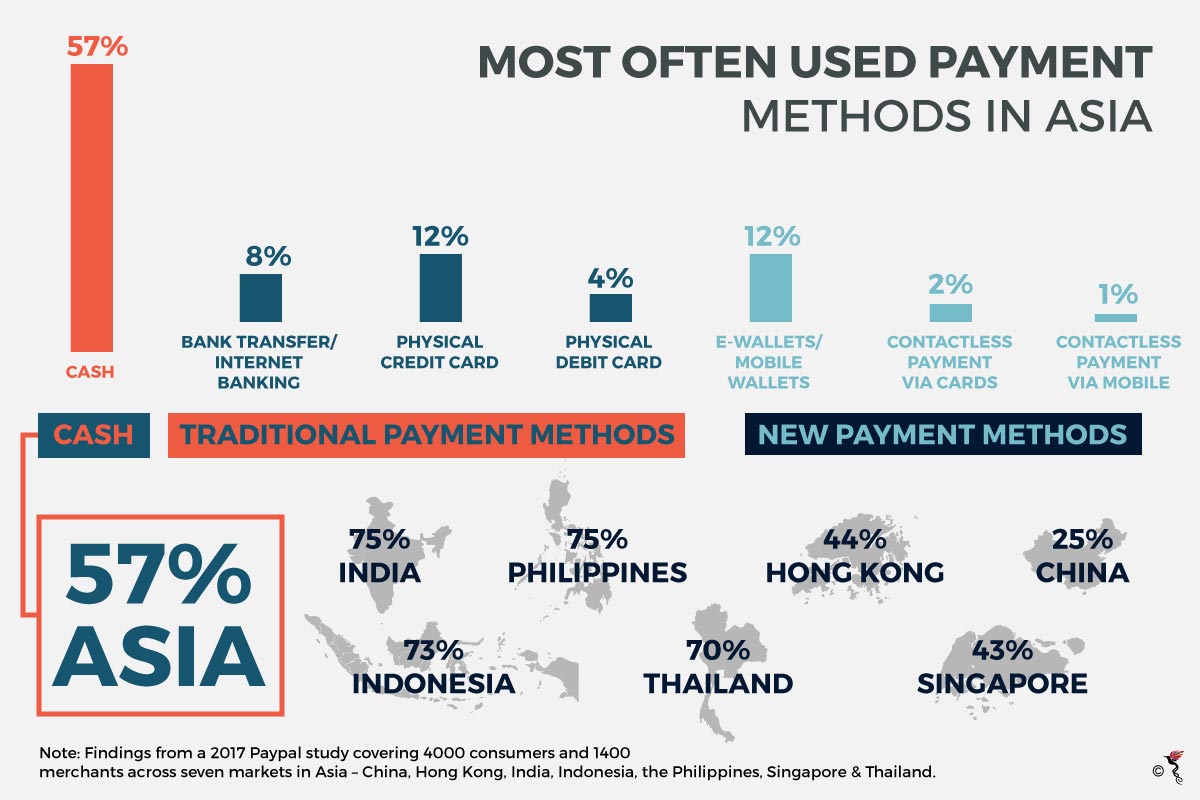

Source: PayPal

In fact, Malaysia could be its stepping stone to the rest of Southeast Asia. The region however may still lack the necessary tech infrastructure to accompany rapid growth.

It remains doubtful whether Southeast Asian governments will allow foreign companies to dominate the payments infrastructure without some regulation. In order to set the pace, they have introduced digital payment solutions of their own. Singapore’s PayNow and Thailand’s PromptPay are both examples of governments initiatives to introduce digital payments they can regulate.

Singapore’s PayNow, for instance, allows registrants to transfer money from their bank accounts using just their identification card numbers or mobile numbers. It also teamed up with Thailand’s PromptPay, which runs a similar system, to facilitate seamless payment transactions between the two countries.

Though it is arguably the role of governments to set the pace for digital payments growth in this region, it also needs to set clear guidelines. Most recently, the Bank of Indonesia forbade digital payments facilitated through QR codes because they were deemed to be in violation of central bank regulations. This is despite Go-Jek’s GoPay platform having been run as a separate platform from the Go-Jek ride-hailing platform since November 2017.

There is no one method for e-payments providers to achieve success in Southeast Asia. Foreign providers have already built their markets overseas – and are able to adopt a wait-and-see approach for now. Meanwhile, governments will need to take the initiative by building their respective regulatory frameworks for digital payments providers. At the same time, governments will also have to ensure that their digital payments solutions meet or exceed the standards of their foreign counterparts.

Related articles:

Philippines, the most dangerous country in Southeast Asia for journalists

Bank Indonesia signals no more rate cuts as inflation risks rise