Southeast Asia has varying wind energy resources with Philippines leading the way in terms of having the biggest potential. According to International Energy Agency’s (IEA) 2017 Southeast Asia Energy Outlook report, it is stated that the Philippines has an estimated technical potential of “around 70GW”.

Indonesia - Southeast Asia’s largest economy - has attractive demographics and a surging power demand, but wind energy development has been sluggish compared to neighbouring countries.

The archipelagic country has an estimated total potential for onshore wind energy of 9.3 GW, according to the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). Based on the distribution of the evaluated sites and the identified short-term potential across wind locations, it is estimated that nearly 85 percent of wind power potential is in the Java-Bali, Sulawesi and Nusa Tenggara regions. The Indonesian government targets 1.8 GW of installed wind capacity by 2025, with capacity factors estimated at 20-30 percent, stated IRENA.

IRENA also assumes that the installed capacity will further expand to 2.6 GW by 2030, 28 percent of the total potential identified so far. About 74 percent of wind energy potential is assumed to be on Java-Bali, given the combination of good wind resources and a high demand for electricity.

Offshore wind energy has not been included in Indonesia’s renewable energy goals as its application is not considered feasible at present, given that the potential area is mainly located in the Indian Ocean, where costs are anticipated to be high due to sea depth.

Indonesia’s first wind farm

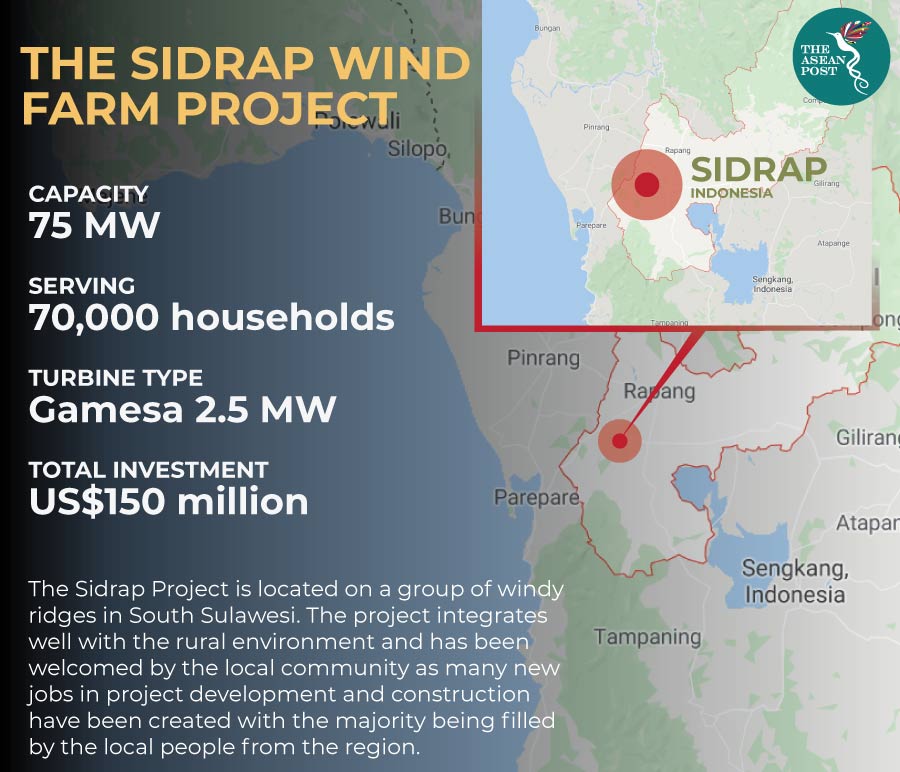

Indonesia’s first ever utility scale wind farm - which is also the biggest in Southeast Asia – is located in Sidrap, South Sulawesi. The Sidrap Wind Farm project when completed is expected to produce 75MW of electricity using 30 Gamesa 2.5MW turbines. The project is currently said to be 90 percent completed and is slated to be up and running by March 2018, according to the project’s developers, PT UPC.

A spokesperson of state-owned electricity company Perusahaan Listrik Negara (PLN), said to The Jakarta Post that “…the Sidrap Wind Farm is part of the 35,000 MW electricity program.” Another PLN official also stated that the wind farm uses “…40 percent local materials and will employ 500 people” and produce electricity for up to 70,000 households.

Deployment challenges

Wind energy in Indonesia is currently still a small component in the country’s overall energy mix. However, it may be the most important form of renewables when it comes to accelerating energy production in the country.

One major challenge that Indonesia faces in deploying wind energy is cost. The cost of developing wind energy is very high, especially with the use of off-shore wind turbines. IRENA indicates it costs around US$3 to 4 million per MW to build off-shore wind turbines, compared with geothermal power plants that cost around only US$2 to 3 million. Coal-powered plants have an average capital cost of less than US$1 million per MW, which of course makes it more appealing for deployment.

Another challenge is the cost for analysis when selecting the best possible energy generation method to suit the Indonesian geographical landscape. Due to the many alternative energy sources available in this archipelagic country, such as geothermal, coal and solar, it is rather challenging for cost analysis to be carried out.

A cleaner future

Indonesia has set a target for renewables to make up nearly one-quarter of its energy mix by 2025 from around just 12 percent at present, with 1,800 MW of wind projects targeted for completion, according to IRENA.

Environmental benefits aside, deploying more renewable energy in the country also means that consumers will enjoy lower power rates in the long-term.

“Transitioning to cleaner energy will protect us from the changing policies of nations where we purchase our fuel and coal from as well as their diminishing supply,” said Guido Alfredo, President and CEO of Emerging Power Inc. (EPI) This will affect consumers who will end up paying higher prices when coal or fuel prices spike.

Choosing renewable energy such as wind means that power rates will be fixed as opposed to traditional power sources where prices are vulnerable to a variety of developments, globally. Since the energy will be sourced internally, the economy will not be exposed to the fluctuations of an international market.

Related articles:

What does China mean to Cambodia?

Thailand’s EEC on track to support next wave of industrialisation