Oil and gas are finite resources. Although they can generate substantial revenue for national coffers, they cannot be relied on indefinitely. As an oil and gas producing country develops, its domestic demand for the commodities will grow and gradually cancel out financial gains.

Oil was a big component of Indonesia’s economy ever since it was first discovered in north Sumatra in 1885. In 1962, Indonesia became the first and only Southeast Asian member of the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) until it voluntarily suspended its membership in 2008.

However, its domestic oil consumption overtook production in 2002 and it became a net importer of oil. This was compounded by declining production, down from its peak of nearly 1.7 million barrels per day (bpd) in 1991 to around 779,000 in May this year.

The republic’s dwindling reserves is largely due to a lack of investment in exploration, which shrank from US$1.3 billion in 2012 to just US$100 million in 2016. Investors were also wary of constant regulatory changes. The government there recently revised rules to reduce red tape but changed a system that reimbursed contractors for costs associated with exploration and production.

In another sweeping move on 12 September, the Indonesian government ordered all domestic oil production to be sold to state-owned company PT Pertamina, in a bid to reduce crude oil imports and shore up the weakening rupiah. Oil companies are only allowed to export oil to fulfil existing contracts.

Uncertainty is also threatening oil and gas investments in Malaysia. A newly-installed federal government is grappling with oil rights ownership and royalty payments with two of its main oil producing states, Sabah and Sarawak. Both states are asserting their rights over their natural resources and challenging the legitimacy of PETRONAS, a government-owned company vested with all Malaysia’s oil and gas rights.

Similar to Indonesia, Malaysia is facing dwindling oil reserves and has been a net oil importer since 2014. Instead of gaining additional revenue as global oil prices rose, the Malaysian government found itself spending US$386 million between May and July this year to keep petrol prices at US$0.53 per litre. A targeted fuel subsidy system is planned next year to minimise the drain on national coffers.

Thailand’s oil production peaked in 2012 at 574,000 bpd and has since dropped to 256,000 bpd in 2016. It is a net oil importer and has also resorted to introducing oil subsidies to cushion the rise in global oil prices. The government there has set aside US$919 million to absorb 50 percent of any increase in retail prices.

As domestic consumption increases and oil prices rise, subsidising fuel will be an ever-growing expense. Governments may not be able to sustain subsidies during the next oil price boom. If subsidies are discontinued suddenly then, it may trigger a sharp increase in the price of goods and services across the board.

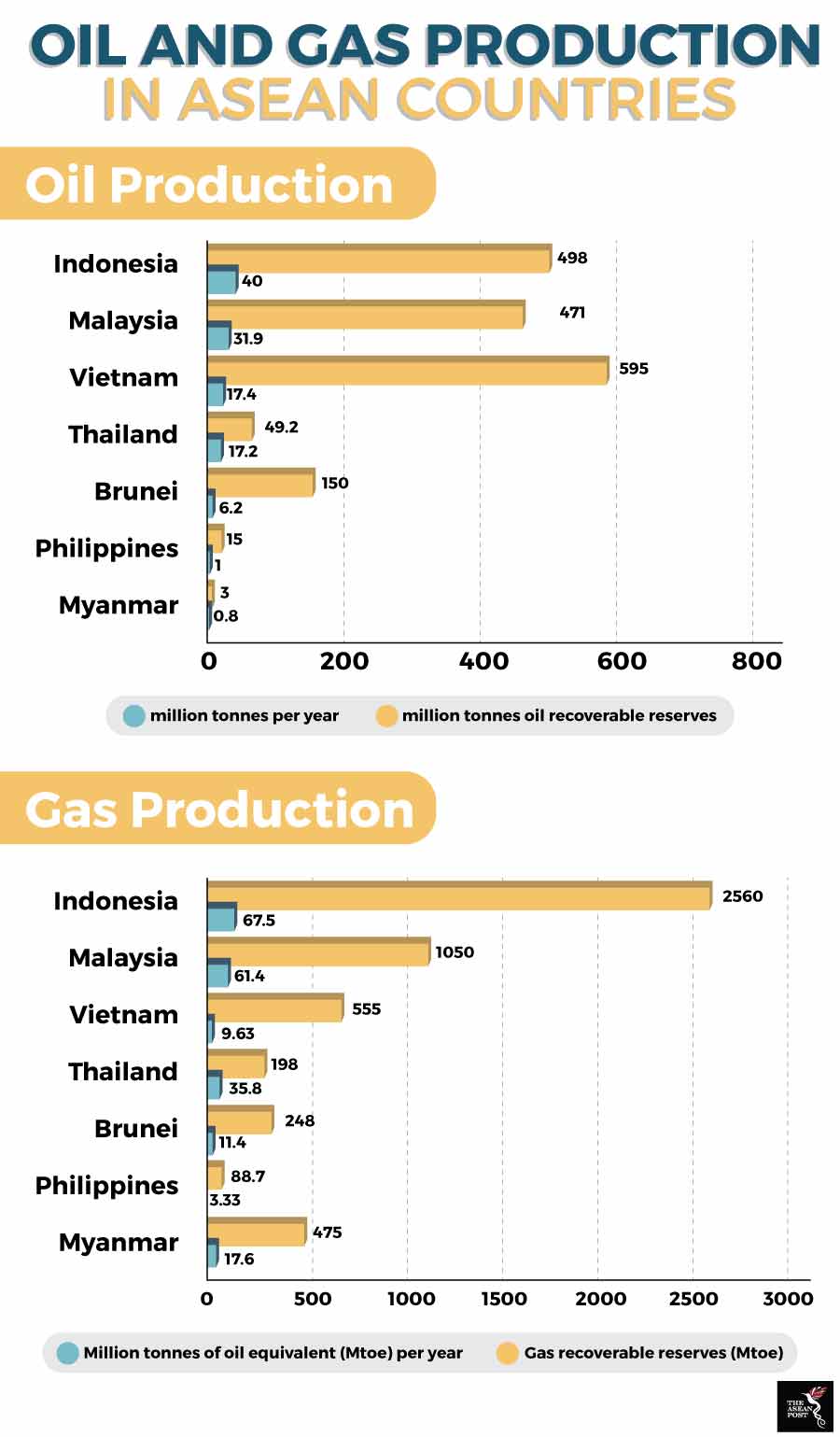

Source: World Energy Council

Source: World Energy Council

Vietnam’s oil and gas industry contributes some 28 to 30 percent to the state’s budget annually. Its oil reserves are said to be the second largest in East Asia, after China. Like Malaysia in its petroleum heyday, oil is fuelling Vietnam’s development. It is also looking to develop gas reserves in the South China Sea despite objections from China.

Myanmar has one of the world’s oldest petroleum industries, dating back to 1853. However, economic isolation and sanctions have caused the industry to stagnate. Today, Myanmar is a natural gas producer and exporter. It is opening up several oil and gas blocks for tender next year to boost production.

Brunei’s development was supported almost entirely by exports of oil and gas. However, its reserves are expected to run out in 20 years, prompting the Sultanate to urgently diversify its revenue sources.

The Philippines is a net importer of oil but a new inland oil deposit discovered in Cebu this year may reduce its dependence on imports. The government is also working out an arrangement with China to jointly explore for oil and gas in parts of the South China Sea that are currently contested by both parties.

Oil and gas reserves are essentially measured as known quantities that are commercially viable for extraction. As the fields are tapped, the oil and gas become gradually more difficult and expensive to extract. The difficult-to-extract resources will only be extracted if the price is high enough to make it worthwhile.

“The size of resources is affected by a number of factors such as fiscal regime, subsurface conditions, and of course, the price at which the hydrocarbons can be sold,” said Neil Semple, Principal of Asia Pacific energy consulting, Poyry Energy.

“In the more mature gas-producing nations of Malaysia and Indonesia, gas reserves have essentially plateaued, and in Thailand declined, in the last 15 years, whereas in Vietnam and Myanmar they may be raised in future as they still have unexplored basins with good prospects.

“All these nations’ gas reserves could probably be higher if domestic gas has a higher price and one similar to internationally traded liquefied natural gas (LNG),” he said.

Related articles:

The role of fuel subsidies in Southeast Asia