As an economic bloc, ASEAN is the fifth largest economy in the world. However, this is not reflected in the adoption of digital transformation. ASEAN member countries rank from top to 160 positions on the global Digital Adoption Index (DAI) published by the World Bank.

Singapore sits atop the ranking followed by Malaysia in a distant 41st place; Thailand (61); Brunei (58); Vietnam (91); Philippines (101); Indonesia (109); Cambodia (123); Lao PDR (159) and Myanmar (160).

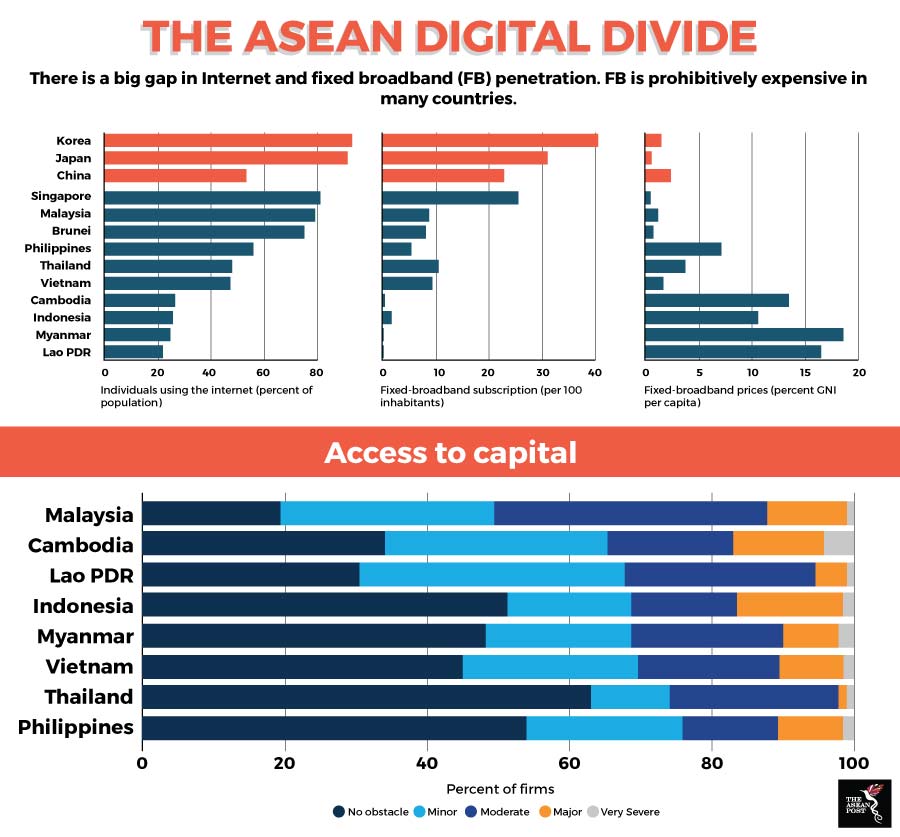

Internet connectivity is the basic requirement for participating in the digital economy. On the consumer side, Internet connectivity via fixed line and mobile data are sufficient. However, for businesses, fixed broadband Internet is essential as mobile internet is both, too slow and expensive. In this regard, Internet penetration is lower.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has said that Internet penetration is high in countries such as Brunei, Malaysia and Singapore. However, in less developed countries such as Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR and Myanmar, approximately 70 percent of the population there have no access to the Internet at all.

The adoption of high-speed Internet using fixed broadband in ASEAN member states is hampered by high costs. Among the six largest economies in ASEAN (ASEAN 6), Singapore has the lowest high-speed Internet cost at US$0.05 per megabit (Mbit) per month, followed by Thailand (US$0.42); Indonesia (US$1.39); Vietnam (US$2.41); Philippines (US$2.69) and Malaysia (US$3.16).

Fixed-line broadband not only leads to faster mobile Internet speeds but also lets businesses better cope with video streaming, manage their supply chains on cloud computing and for governments to coordinate their agencies in real time. “Without ultrafast broadband, innovations such as artificial intelligence (AI), the Internet of Things (IoT) and Industry 4.0 will not be feasible,” said Richard Record, lead economist, World Bank Group, recently at a forum in Penang, Malaysia.

The high cost of fixed-line broadband has resulted in lower adoption rates especially among small-to-medium enterprises (SMEs). Larger companies typically adopt digital technologies more readily to engage in e-commerce. This goes against the presumption that the Internet provides a level-playing field that enables newer, smaller, entrepreneurial companies to enter the marketplace and thrive.

There is a risk of a widening digital divide within each country where large companies dominate smaller companies that lack the resources for digital transformation. This can undermine a country’s plans to turn its digital economy into an engine of growth.

Source: International Telecommunication Union and World Bank

Source: International Telecommunication Union and World Bank

Likewise, the digital divide between countries in ASEAN may also widen as businesses opt to relocate their operations in countries with the fastest and cheapest connections. These countries are also preferred by investors looking for the next unicorn.

Start-ups get relatively easy access to financing during pre-seed and seed stages. In countries such as Malaysia, government programs provide seed funding and connections to private-sector investors. However, venture capital firms play a more important role in the early growth stage of these companies with their expertise and mentorship.

As of March 2018, there are 61 registered venture capital firms in Malaysia. In comparison, Singapore has 593. Many investors insist that entrepreneurs register or have holdings in Singapore as the country provides better protections and incentives for foreign investment.

Other ASEAN 6 countries must create a more attractive investment climate to entice private capital for their entrepreneurs. If they do not act fast, the digital divide between ASEAN nations will widen further to the detriment of their digital economies.

The IMF prescribes five key priorities for growing the digital economy. It says that Internet connectivity must be made universal and affordable; the business climate must encourage competition which spurs innovation; education systems must adapt workers’ skills to meet new demands of the digital future; countries need to strengthen safety nets to protect workers displaced by automation; and countries need to adapt their regulatory frameworks to improve financial inclusion with technology and manage fintech-related risks.

With digital gaps within and among ASEAN nations, the bloc faces difficulty benefiting from the digital economy as a whole. With the exception of Singapore, ASEAN lags behind China, Japan and Korea in broadband penetration. Unless the association acts quickly to close this gap, its weaker members may lose out in the digital race against the likes of China and India who are already advanced in information technology services and skilled manpower.

Related articles:

The key to greater ASEAN digital integration