Originating in the Tibetan highlands and running through China, Myanmar, Thailand, Lao PDR, Cambodia, and Vietnam, the Mekong and its tributaries provide water, food and income for 60 million people. The longest river in Southeast Asia is home to the world’s largest inland fishery. It is estimated that 25 percent of the global freshwater catch is harvested from this river.

Damming of the Mekong started in China in the early 1990s. However, most of the river remained undammed due largely to the regional cooperation between the lower Mekong member states. In 2006, energy needs magnified by the financial returns of hydropower drove Lao to kick off its first dam on the river, as well as dozens more on its tributaries. Other lower Mekong countries followed suit.

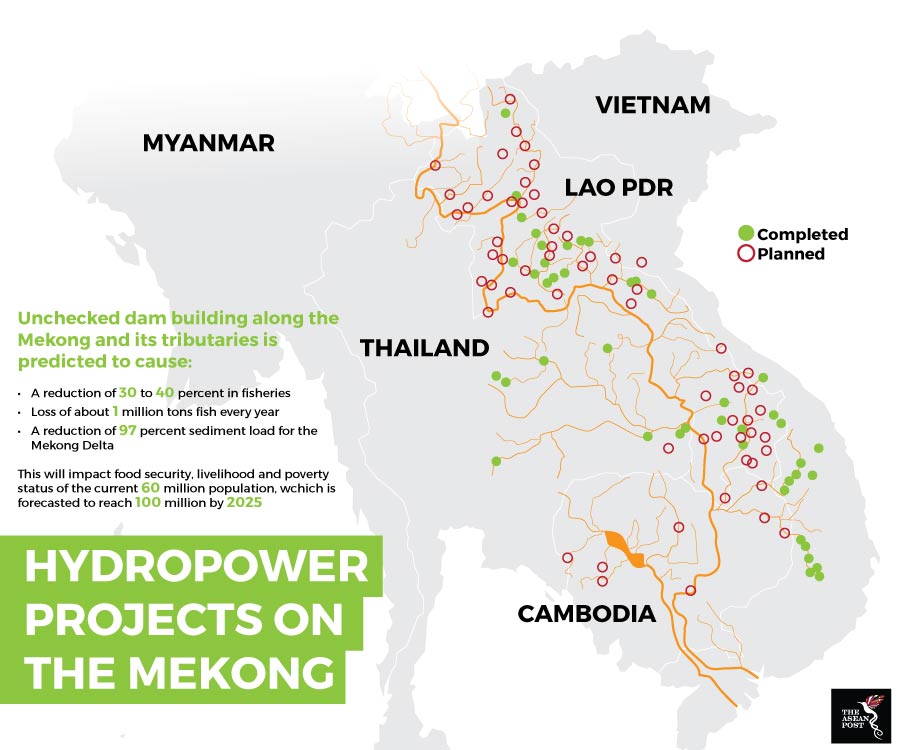

Concerns have since been raised on the massive negative impacts and trade-offs of the numerous detrimental hydropower developments along the waterway. A Mekong River Council study discussed at the Mekong River Commission (MRC) Summit earlier this year predicted a reduction of 30 to 40 percent in fisheries, involving the loss of about one million tons of fish every year.

The study also predicted a reduction of 97 percent sediment load reaching the Mekong Delta, which will colossally reduce soil fertility in the lower Mekong basin, leading to a decrease in the region’s agricultural productivity, as well as increased poverty and food insecurity.

Source: Various sources.

Stopping the migration

The impact of damming on fisheries occurs during all stages, including during construction, commissioning and operation of the dam. According to an MRC report on dam impacts mitigation on fisheries, besides the changes in seasonal and daily flow, the fish population could also be impacted by sediment and other particulate trappings leading to stratification, in which oxygen becomes depleted in the deeper sections of the river resulting in anoxia, increased toxicity and other negative effects on water quality.

Environmentalists and researchers in the Mekong area are also concerned that the environmental impact assessment done on behalf of dam developers not only downplayed the environmental damage, but also overlooked the transboundary effects of river damming, which could devastate the Mekong’s fish populations.

Damming rivers also expose fish populations to barrier effects, where the dam blocks their movements and causes injury when they swim up- or downstream. The migration is crucial as spawning habitats of different species may be located in different parts of the river and its tributaries. In the case of the Mekong, this is critical as these patterns have been fine-tuned over millennia to accommodate one of the most diverse assemblages of fish species found anywhere in the world.

“Fish in the Mekong have strongly adapted to the flow regimes of the river. If the fish cannot adapt to the new system, they’re gone,” said Peng Bun Ngor, a fish ecologist with the Cambodian Fisheries Administration.

Food security, livelihood and sustainable development

For many people residing in the Mekong’s lower basin, the reduction in fish landing and the impact of dams on their fish landings and food security have already been felt. According to Rivers International, an organisation promoting rights of rivers and its communities, the impacts are expected to result in a drastic reduction in food security and agricultural productivity, alongside increased poverty levels and heightened climate vulnerability in much of the Lower Mekong Basin.

“Achieving sustainable development in the Lower Mekong Basin is dependent on the availability of natural capital and the preservation of biodiversity. Particularly important are healthy soils, watershed and riparian forests, and seasonally flowing rivers to support the world’s largest inland fishery. Current plans for large-scale hydropower dams are certain to decrease resilience, increase vulnerability, and reduce sustainability in each of the Lower Mekong member countries,” it said in a statement.

The world’s largest and most productive inland fishery, with more than 850 fish species, is well and truly threatened. The ecosystem and ecosystem services destruction may hark the devastation of the Mekong river and threaten its population, projected to rise to 100 million by 2025. The enormous number of dams being plotted on this magnificent river threatens not only its biodiversity but also diminishes its role as a unifying force of nature for the many countries along its banks.

Related articles: