Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) or drones are usually associated with military applications but they also have immense usefulness in agriculture.

Drones are used in Japan’s rural heartland to aid the aging farmer populace spray pesticides and fertiliser. The median age of farmers in the rice-planting region of Tome is 67 years. Similarly, Thailand’s agriculture industry is aging as youngsters below the age of 30 are shunning the profession.

Most farms in developing countries are small and unproductive and young people are leaving in search of city jobs that provide higher salaries. The farms are abandoned or left to the older folk, said Sohail Hasnie and Sungsup Ra from the Asian Development Bank (ADB) in a paper presented at the World Economic Forum (WEF) in March.

Drones can make farming easier and more profitable, said Hasnie and Ra, and may even attract the youth back from the city. They urged developing Asian countries to anticipate future uses for drone technology.

Precision farming

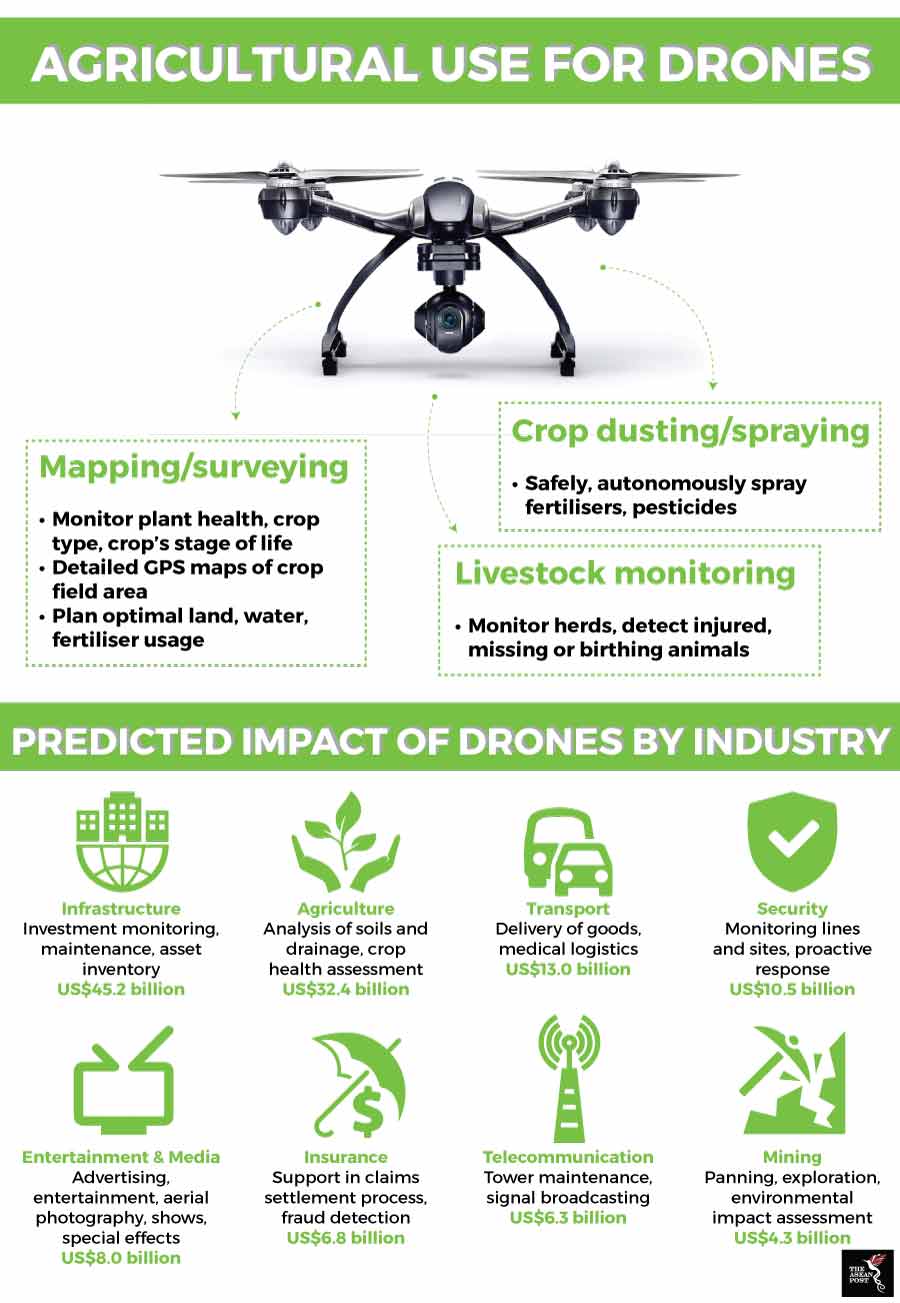

“Drones make precision farming a reality. They can carry out surveys like infrared mapping to gather crucial information like crop condition, costing farmers as little as US$5 per acre. With the data, they may be able to boost crop yields by 20 percent,” they said.

Today’s drones are relatively inexpensive. An unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) from a mainstream manufacturer costs as little as US$400 and a complete system for a small farm costs around US$5,000. An octa-copter drone requires US$1.20 worth of electricity to carry a 10-kilogram payload for 30 kilometres.

Farmers can pool their funds to buy and share a drone. An agro-preneur can invest in a unit to serve multiple farmers or villages for a fixed membership or per use fee, suggested Hasnie and Ra.

“Once drones can work autonomously, farmers can operate them through a smartphone app. It will be a cheap, high-quality service with no ownership or maintenance fees, and include performance benchmarks based on crop type, topography, geography or climate condition,” they added.

Spraying fertilisers, herbicides and pesticides with UAVs is safer and faster than doing it manually and uses fewer quantities of chemicals. In Vietnam, pesticide inhalation kills over 300 farmers each year and seriously affects another 5,000.

Source: Dronefly.com, PwC

Drones can also generate Normalised Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) maps which can differentiate soil from grass and forest, identify the growth stage of crops and detect plants under stress. Drone images can also be used for loss or damage in agriculture insurance assessment.

UAVs in ASEAN

However, the use of UAVs in ASEAN member states is currently limited. Japan’s DMM Technologies’ drones are used to spray pesticides on rice fields in Can Tho, Vietnam. The company also conducted trial spraying for sugar cane in Tay Ninh and rubber trees in Gia Lai.

The Philippines began a trial in April using DMM drones to spray vegetable farms in the highland province of Benguet.

In Malaysia, six drones were used by the Muda Agriculture Development Authority (MADA) for its Paddy Estate Project, covering 2,000 hectares. Drone-maker MMC said it has a customer who used its drones to fog and spray pesticide in his durian plantation.

Thailand’s Kasikorn Research Centre estimated the nation’s agricultural UAV market to be worth US$181 million by 2021 based on the government’s ambitious “Big Farm” project. Launched in 2016, the project aims to help neighbouring farmers integrate their farmlands and share production costs, making it more affordable for them to embrace agri-tech.

The main barrier to widespread drone usage is regulation. Every government has its own set of regulations on UAV, due to the risks posed by UAVs to the aviation industry and security in general. The rules are stricter for drones that fly beyond the visual line of sight (BVLOS), which is necessary if they are to be used to inspect large tracts of farmland.

Governments will also need to modify licencing and operating regulations for farm drones and perhaps require certain limitations to be built into their specifications.

In time and with farm drones, agriculture may become less labour-intensive and even attract a new generation of young, tech-savvy farmers.

This article was first published by The ASEAN Post on 28 August 2018 and has been updated to reflect the latest data.

Related stories:

ASEAN’s role in global food security

Insuring farmers for food security