Just as martial law in Mindanao was nearing its expiration, the Philippine Congress approved on 12 December a 12-month extension of the law. The extension received an overwhelming majority in Congress with 235 lawmakers voting for it.

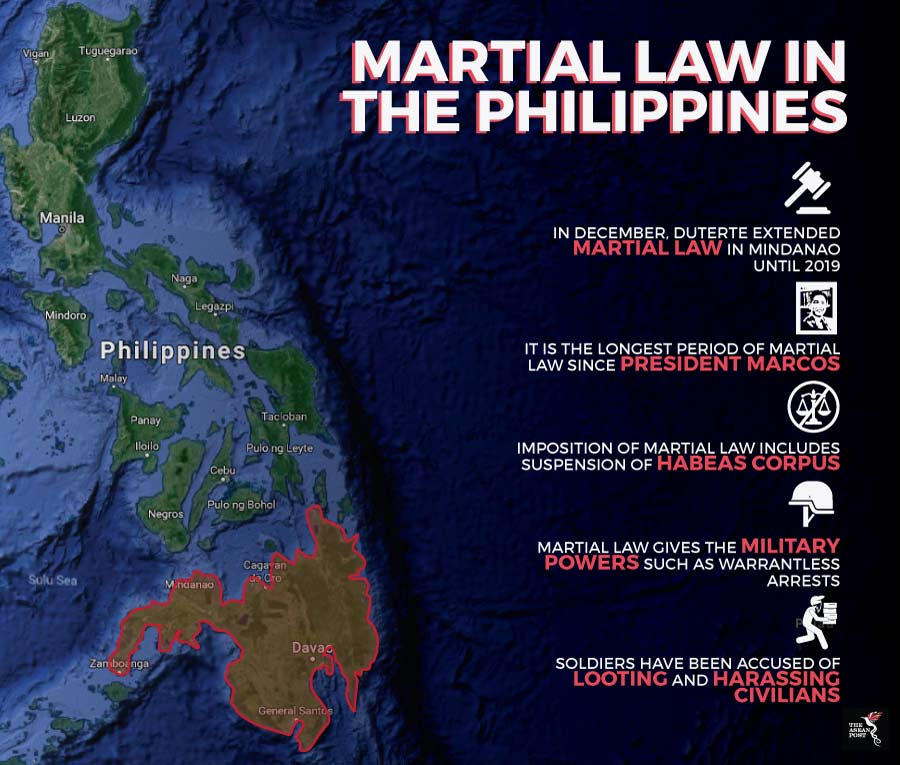

Martial law in the Mindanao region was first implemented in May 2017, after hundreds of Islamic State (IS) affiliated militants took control of the city of Marawi. The siege lasted five months and saw over 47 civilians and around 970 militants killed. In December 2017, Philippine president Rodrigo Duterte extended martial law until the end of 2018, making it the longest period of martial law since the Marcos administration.

According to Duterte, the latest extension was necessary as the terrorist threat in Mindanao has yet to be completely eradicated.

"Notwithstanding the substantial gains achieved during the martial law period, we cannot turn a blind eye to the reality that Mindanao is in the midst of rebellion," Duterte said.

While the decision to extend martial law is widely supported in congress, there are also fierce critics of the extension.

Source: Various

Source: Various

Dark past

The Philippines has had a dark past when it comes to martial law. During the Marcos administration, martial law was declared in 1972 amid growing unrest and the threat of a communist insurgency. Martial law was in place for almost 10 years, ending with the People Power revolution. Martial law under President Marcos was marred with various abuses, ranging from torture methods employed by the army, extrajudicial killings and the arrests of journalists.

Duterte claimed that the extension of martial law was essential in combating radical Islamic insurgents and communists.

However, opposition members of the house have questioned the need for an extension, claiming there is no real rebellion coming out of Mindanao. They have also brought up the various claims of human rights abuses in the region.

Many have claimed that the increased military presence in the area following martial law has led to abuses by the military. Among the allegations made is that the military has been looting the remains of the siege. There are also reports of locals being harassed and extorted by the armed forces and national police.

The Lumad people who are indigenous to Mindanao have also spoken out against the extension of martial law as they have been regularly targeted by the Philippine army. The Lumad people have traditionally been accused of cooperating with communists, hence making them easy targets for the army. Their community has been under attack with illegal arrests, extrajudicial killings, harassments and many more. More than 44 Lumad schools were closed last year due to alleged intimidation by soldiers and paramilitary. Duterte even threatened to bomb Lumad schools in July last year, claiming that they were violating laws by spreading subversive ideas.

One of the biggest fears stemming from Duterte’s extension of martial law is that he could use this period of time to consolidate his power similar to what Marcos did. One of Duterte’s reasons for extending martial law is to combat a supposed communist rebellion there. The active communist group, the New People’s Army was allegedly behind the kidnapping of two soldiers and 12 members of the paramilitary force. Observers argue that martial law is not necessary to combat these communists. Instead, martial law would allow Duterte to target critics with impunity as he has been known to dismiss his opponents as communists.

Others also fear that there could be no end in sight for martial law. Now that Duterte has extended an initial 60-day martial law period to two years, who is to say that he won’t extend it for the rest of his presidency?

With martial law extended for another year, there are fears that human rights violations in the region will continue and even increase. If martial law is truly there to protect the citizens of Mindanao – and to a larger extent, the rest of the population – then the military enforcing it needs to do the same too.

Related articles:

Preventing another ‘Battle of Marawi’

The Philippines: Dangerous for journalists