Thailand’s ratification of the International Labour Organisation’s (ILO) Work in Fishing Convention on 30 January has won it international plaudits – but how well will it be received locally?

As the first country in Asia to ratify ILO’s Convention 188, Thailand – the world's third-largest seafood exporter – has received praise for “setting an excellent example” to ensure acceptable living and working conditions for fishermen onboard ships, according to ILO Director-General Guy Ryder.

But with human rights abuse rife in the Thai seafood industry – a United Nations (UN) report found that 59 percent of trafficked migrants working on Thai fishing vessels reported witnessing the murder of fellow workers – for many, the ratification is nothing more than a fancy PR stunt.

In addition, corruption, long-established poor fishing practices and resistance from fishermen associations in Thailand to what it claims are strict standards means the implementation and enforcement of Convention 188 will be contentious.

Rampant abuses in Thai fishing industry

Half of the estimated 600,000 men working in the Thai seafood industry are undocumented workers from countries such as Myanmar, Cambodia and Lao PDR. Forced labour and other human rights abuses among them have been well documented in a series of media exposés dating back to 2014.

Exhausted Thai fish stocks require vessels to stay out longer at sea and go further afield, often fishing illegally in other countries’ territorial waters, according to a 2015 report by the Environmental Justice Foundation (EJF) titled, Thailand’s Seafood Slaves: Human Trafficking, Slavery and Murder in Kantang’s Fishing Industry.

Operators use human trafficking networks and bonded, forced and slave labour to run their vessels and save costs. With supply ships regularly restocking deep sea fishing vessels and taking caught fish back to port, some vessels are out on the seas for years – and so are their abused fishermen, most of whom have no chance of escaping.

“Despite high-profile commitments by the Thai government to clean up the fishing industry, problems are rampant,” said Brad Adams, Human Rights Watch (HRW) Asia Director when announcing a HRW report titled Hidden Chains: Rights Abuses and Forced Labour in Thailand’s Fishing Industry in a briefing at the European Parliament on 23 January.

In 2017, a survey by an anti-slavery NGO called International Justice Mission found that 76 percent of migrant fishermen in Thailand had amassed debt – often to the ship captains – before they even start work, with 14 percent suffering abuse and 32 percent witnessing abuse.

Brokers promise workers jobs in Thai factories or farms before smuggling them into the country and selling them to ship captains. With corruption ingrained in the industry – policemen, community leaders, businessmen and politicians all close one eye to the horrors happening at sea.

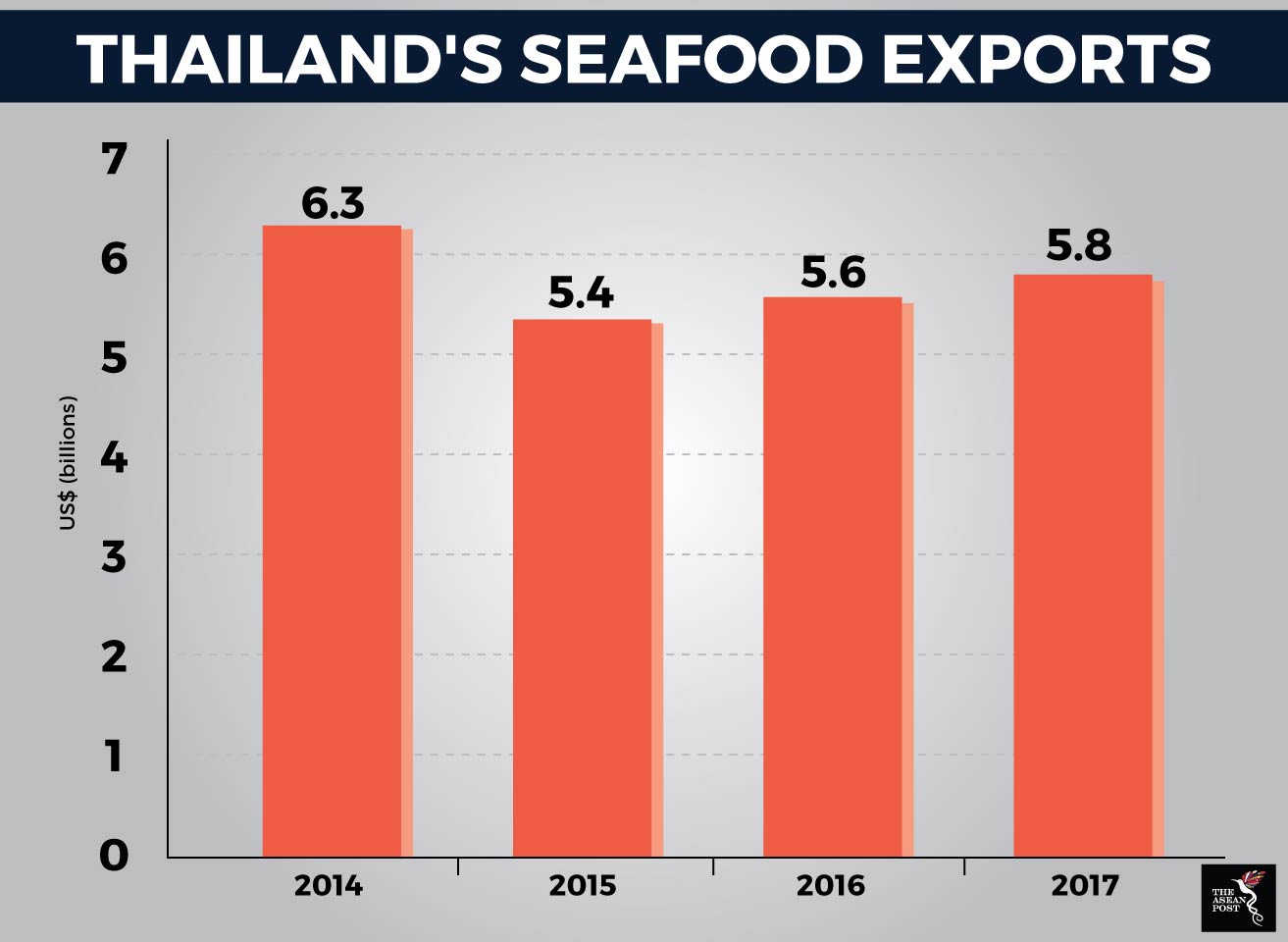

Source: United States Department of Agriculture

Source: United States Department of Agriculture

International repercussions

The United States Department of State downgraded Thailand in its annual Trafficking in Persons (TIP) report to Tier 3 in 2015 after news reports about murders and other human rights abuses on Thai fishing ships. The ranking has now improved to Tier 2 in a move which Thailand says reflects its efforts to combat human smuggling and illegal labour and helps boost its standing among trading partners.

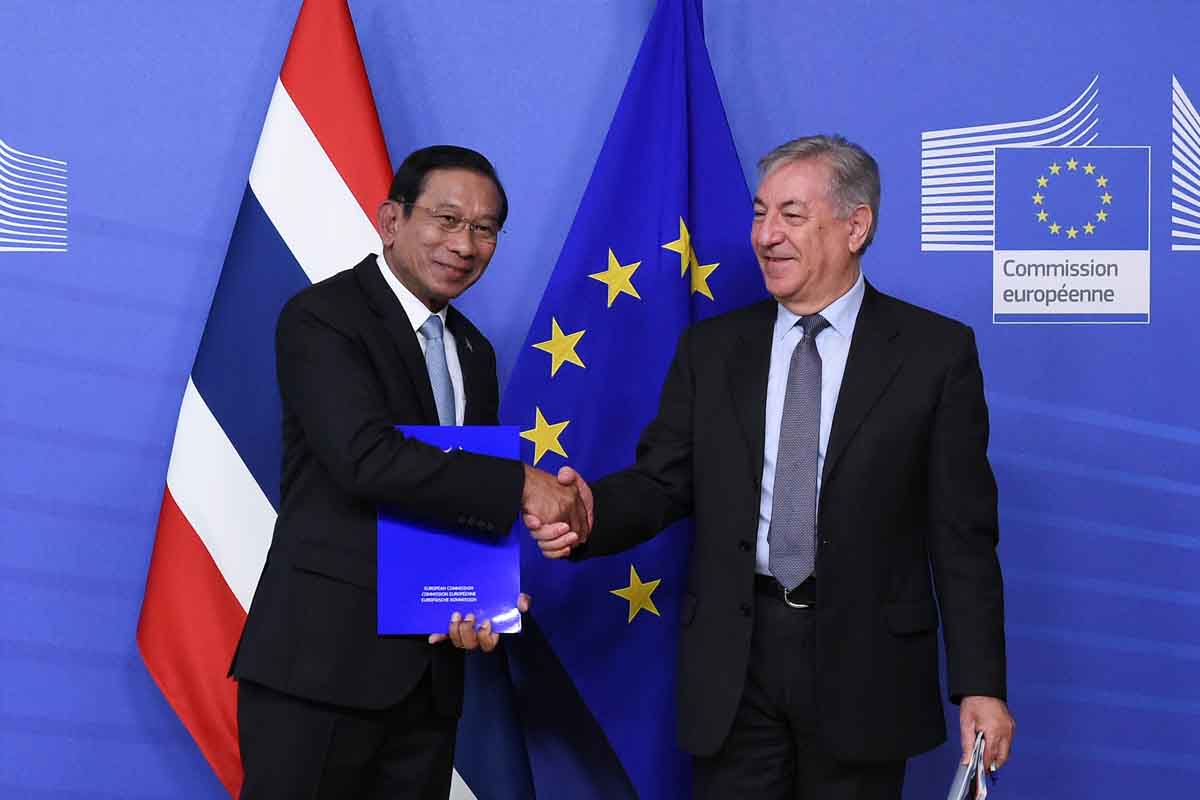

The European Commission, meanwhile, issued Thailand a “yellow card” warning the same year after noting it was not clamping down on illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing – with a “red card” calling for an import ban on fisheries products caught by the country in question. The “yellow card” warning was removed last month after improvements in Thailand’s fisheries legal and administrative systems, and both rulings have spurred the Thai government into action.

‘A theatrical exercise for international consumption’

However, by and large, the fishing industry in Thailand remains unregulated and human rights abuses are still going unpunished.

New regulations which state fishermen have to be in possession of their own identification documents, receive and sign a written contract and be paid monthly are frustrated by employer practices which hold fishermen in debt bondage and ensure they cannot change employers, said HRW.

There are no effective or systematic inspections of fishermen working aboard Thai vessels – taking for example HRW’s 2015 report on human trafficking in which Thailand revealed that inspections of 474,334 fishery workers failed to identify a single case of forced labour.

“The labour inspection regime is largely a theatrical exercise for international consumption. For example, HRW found officials speak to ship captains and boat owners to check documents but rarely conduct interviews with migrant fishermen,” said the HRW report.

In addition, Thai fishermen associations have balked at some of the convention’s measures such as annual health checks for crew, transportation for crew from foreign ports to Thailand, social security schemes and certified good working and living conditions for the crew – citing cost as the main factor.

But with the convention coming into force in Thailand on 30 January 2020 – one year after ratification – Thailand should have sufficient time to ensure compliance and change its long-standing poor fisheries management.

Protecting the rights of fishermen

Human trafficking rife in the region

Protecting Indonesia’s marine resources