When Susi Pudjiastuti took over the Indonesian maritime affairs and fishery ministry in 2014, she inherited a much-downgraded portfolio rife with issues - from illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing to destructive fishing practices. Indonesia’s fishing grounds’ sovereignty had also been neglected due to the magnitude of its waters and inadequate monitoring and enforcement caused by limited budget capacity.

Despite being the world’s largest archipelagic nation and boasting one of the highest marine biodiversities in the world, 115 Indonesian seafood exporters went out of business, while the number of households living off fishery halved to 800,000 between 2003 and 2013. Up until 2014, Indonesia lost an estimated US$4 billion a year due to IUU fishing.

Under President Jokowi’s administration, Indonesia has been working on capitalising on its fertile fishing grounds to boost economic growth. Unlike other bigger-faster-stronger investment and production solutions, Susi’s strategy is sustainability. Her key target is IUU fishing, with the help of Google, arresting transgressors and sinking hundreds of IUU vessels, including from the neighbouring countries of China, Thailand, the Philippines and Vietnam.

Good for the bank and the environment

As a result, its fish stocks increased from 7.1 million tons in 2016 to 12.5 million tons in 2017. Indonesia’s consumption of fish also increased from 36 kilograms (kg) to 46kg per capita last year, according to Susi. Most of the 10,000 poaching foreign boats have disappeared. Indonesia is now the second largest global fish producer.

“For the first time, Indonesia’s gross domestic product (GDP) from the fisheries sector has been growing at an average of six to 6.7 percent per year, exceeding national GDP at the average of 4.5 to 5.2 percent per year. Our competitiveness index in the fisheries sector has also increased by around 20 percent from the previous 107 to 128.

“We’ve proven that we managed to reverse the deficit of our fishery trade balance. Previously, we were behind compared to other countries in Southeast Asia. But during the last four years we’re the first in Southeast Asia,” said Susi at the recently held Our Ocean Conference in Bali.

Source: Various

Source: Various

IUU in Southeast Asia

In its fight against IUU fishing, the European Commission’s (EC) identifies and awards “yellow” and “red” warning cards as well as blacklists countries that disregard IUU fishing. Marine products from red-carded and blacklisted countries are banned from the European Union (EU). EU fisheries companies are also banned from operating in blacklisted countries.

While Southeast Asian countries have declared war on IUU fishing, a number of them have also been carded or banned. The Philippines was yellow carded in June 2014, but had it rescinded in April 2017. Thailand was yellow carded in April 2015 and has yet to have it rescinded. However, the country has been focussed on efforts to reduce IUU, including efforts to ratify the international Work in Fishing Convention, which has raised the ire of its fisher companies.

Vietnam was the latest to get yellow carded in October 2017, and its status will be reviewed in January. Cambodia was yellow carded in November 2012 and blacklisted in March 2014. All fisheries products caught by fishing vessels registered in Cambodia are now banned from entering the EU.

Where the real controversy lies

Susi’s hard-line steering of Indonesia’s maritime governance is seen as controversial, eliciting objections at home and regionally that it could affect international relations. The United Nations (UN) Special Envoy for the Ocean, Peter Thomson, argued instead that the focus should be on how IUU is impacting the fishery industry and the world. He said that, like Small Islands Developing States (SIDS), Indonesia has the huge and unenviable task of policing their waters to stop IUU.

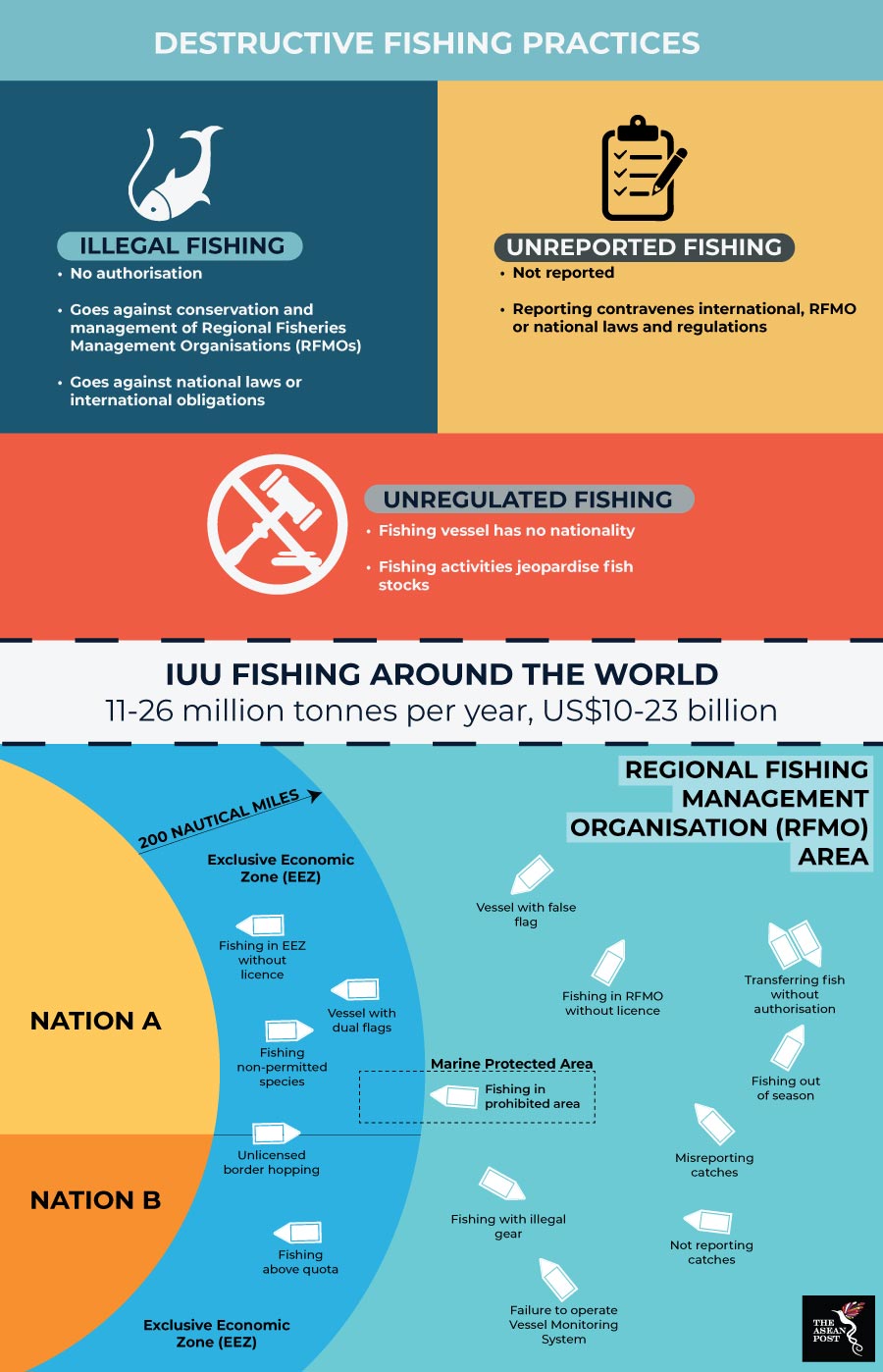

“I think the controversial aspect is that humanity continues to tolerate IUU fishing. US$23 billion worth of illegal fish end up on our plates every year. They are stealing from nature, from society, from the indigenous group with fishing rights and so on. It has to stop,” said Thomson, who is also the Co-Chair of the Friends of Ocean Action, an initiative run by the World Economic Forum (WEF) and World Resources Institute (WRI).

IUU products are pervasive. As stressed by Thomson, whether we are in New York, Kuala Lumpur or Suva, it is likely that we have been the receivers of stolen goods caught under IUU. As consumers, we have to demand that the fish we consume be caught legally and the money we pay for it goes to the right people.

Related articles:

Marine protected areas increasing fish stocks

Fishy business in the South China Sea

Ghost fishing threatens marine life