In December 2018, Cambodian Senate president Say Chhum had encouraged the country’s youth to study hard in order to become future leaders. He made the comment during the opening ceremony of the Union of Youth Federations of Cambodia congress at a hotel in Phnom Penh.

Chhum’s call certainly makes sense if one were to consider how young Cambodia’s population is. According to the Central Intelligence Agency’s (CIA) World Factbook, 30.8 percent of Cambodia’s population is made up of people between the ages of zero to 14 years, 17.8 percent is made up of those between 15 to 24 years, and 41.1 percent is made up of those between the ages of 25 to 54 years. The median age in Cambodia is 25 years.

However, while Cambodia’s population is young, the youth in the country are facing challenges when it comes to acquiring useful talents and skills to cater to the demands of Industry 4.0 or the Fourth Industrial Revolution. To “study hard” in Cambodia is easier said than done.

Education in Cambodia

According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), many young people drop out of school. Access to secondary education shows high inequalities across gender, location and socio-economic groups, with a total secondary net enrolment rate of only 27.7 percent in 2014.

The drop-out rate also gets high when it comes to secondary education, reaching 21 percent in lower secondary in 2014. Although rural and the poorest youth have an improved opportunity to enter higher grades, their rate of school enrolment is still low compared to urban and affluent youth.

Even though higher education remains far beyond the reach of most rural and female youth, the gross enrolment rate in tertiary education among youths aged between 18 and 22 has improved significantly over the last 10 years from 4.9 to 20 percent, including among the poorest households (from 0.2 to 2.6 percent) and women (3.3 to 17.4 percent).

“Both access and quality of education pose crucial issues and indicate a need for more relevant school curricula, sufficiently trained teachers, and more resources for school improvements,” the OECD said.

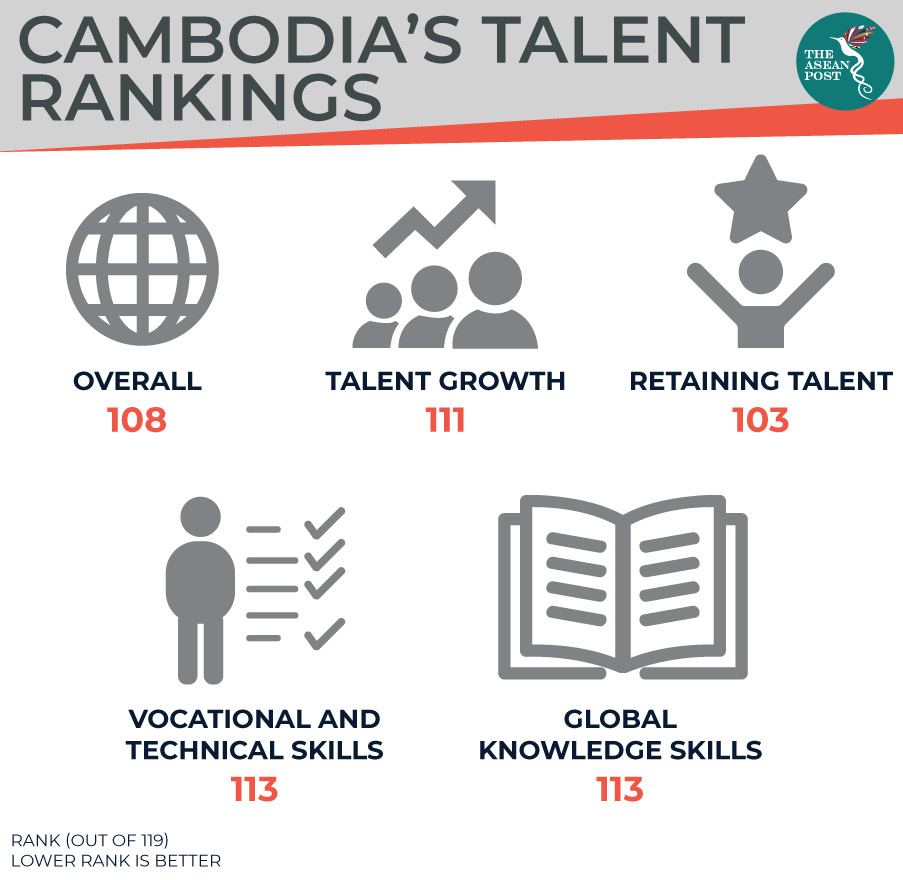

While the organisation cites figures from 2014, the more recent INSEAD 2018 Global Talent Competitiveness Index does not paint a pretty picture for Cambodia either. Out of 119 countries, Cambodia ranked 108 overall. It also ranked 111 for talent growth which includes aspects like formal education, and quality of management schools. It ranked 103 for retaining talent which includes aspects like brain retention; it ranked 113 for vocational and technical skills; and 113 for global knowledge skills.

On one hand, Cambodians who are in school aren’t receiving the right kind of education to prepare them to meet the skills demands of Industry 4.0. On the other, many youths in Cambodia are also already employed and may not have the opportunity to pursue new skills.

According to the country’s Ministry of Planning, 74.5 percent of males aged between 15 to 24 years are employed while the percentage is lower at 68 percent for females. Although these figures are from 2013 (the ministry’s latest findings), a December 2016 report by the Cambodian League for the Promotion and Defense of Human Rights (LICADHO) stated that child labour is still rife in the country.

A recent Blood Bricks research project has led to a photo exhibition exposing debt-bonded labour in the brick making industry. Based on those photos (some of which can be found on the internet) it is clear that many of those working in these brick-kilns are children. This lends some hard evidence to the claim that many of Cambodia’s children are, in fact, working instead of studying.

Chhum’s statement misses the point that whether Cambodia likes it or not, its children will eventually grow up and become the future workforce and leaders of the country. As the old are replaced by the young, a question that Cambodia must ask itself today is whether it is giving its children and youth all the possible opportunities to grow up and become, not just workers and leaders, but capable ones at that.

This article was first published on 4 January, 2020.

Related articles: