Having trouble opening a bank account or transferring funds? Getting stopped by customs officers while travelling abroad? You might have 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB) to thank for that.

Screening processes in ASEAN have risen due to the corruption scandal surrounding Malaysia’s collapsed sovereign wealth fund, with at least US$4.5 billion stolen in a case which former United States (US) Attorney General Jeff Sessions called “kleptocracy at its worst” and led to the downfall of former Malaysian prime minister Najib Razak.

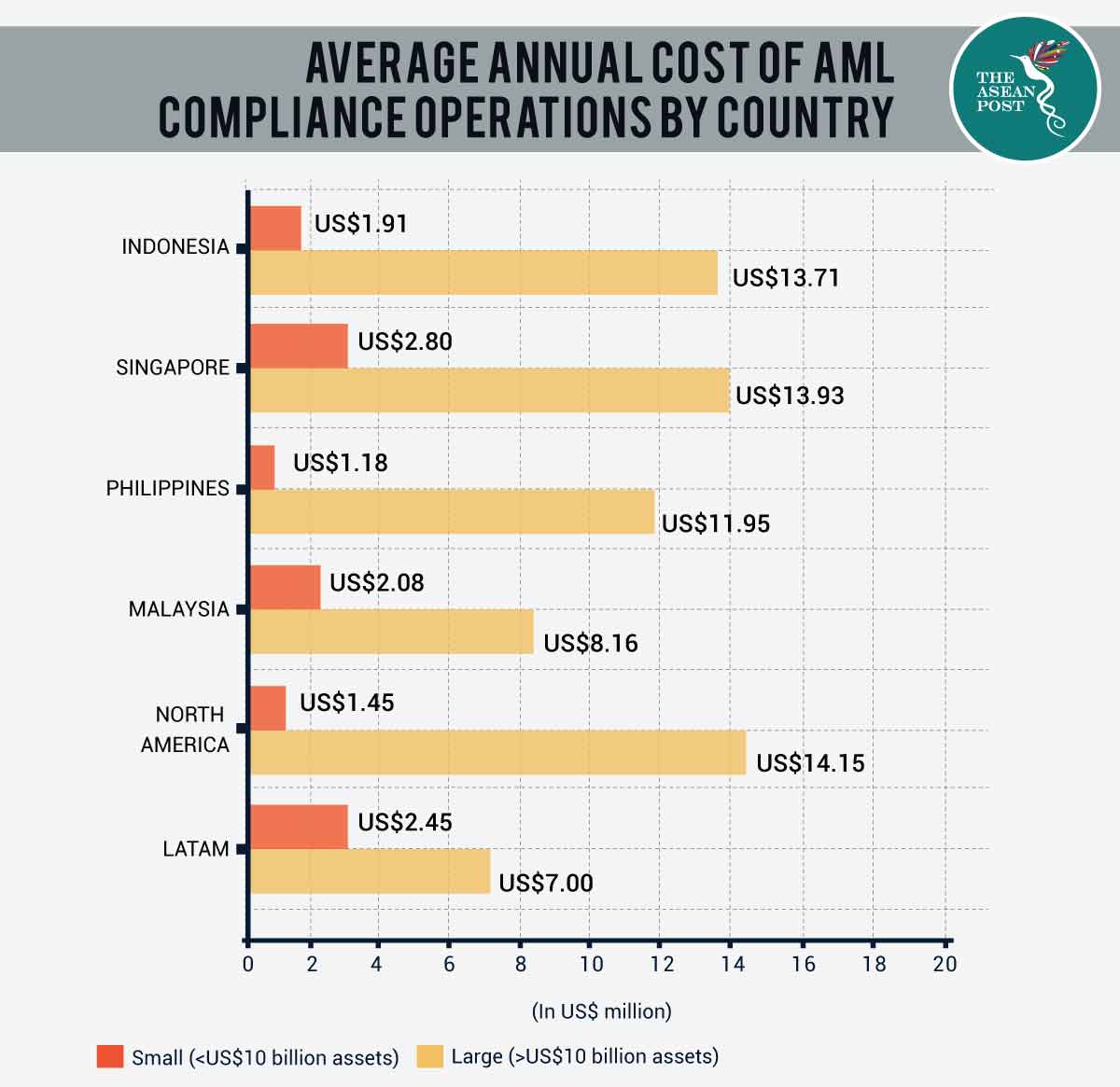

The scandal has led to an eight to nine percent increase in the cost of anti-money-laundering (AML) compliance for companies over the past two years – and the amount is expected to rise by a similar percentage this year according to a recent survey by global analytics provider LexisNexis Risk Solutions.

Titled ‘True Cost of AML Compliance’, the survey estimated the true cost of compliance in Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines and Singapore to be US$6.09 billion annually – with Singapore representing just over half of this amount (US$3.13 billion).

It is only understandable that banks are now strengthening efforts to conduct due diligence on customers and increasing scrutiny of transactions and banking activities, but how does this affect the average ASEAN citizen?

For the retail customer, the biggest impact is during on-boarding (the process of providing information to open a new bank account) explains Chin Yong Kwek, Associate Managing Director in the Business Intelligence and Investigations practice of Kroll – a leading global provider of risk solutions.

‘It boils down to trust’

Chin Yong, who was a former prosecutor at the Financial and Technology Crime Division of Singapore’s Attorney-General’s Chambers – the body which investigated the 1MDB scandal in Singapore – also pointed out that authorities are now keeping a closer eye on transfers of funds to or from certain countries.

There is more enforcement at airports or other border crossings to ensure travellers declare to customs officers if they are travelling with a certain amount of cash – in Singapore, the sum is SG$20,000 (US$14,580).

“Businesses shouldn’t have any problems provided they can prove where their funds came from. At the end of the day, it boils down to trust,” said Chin Yong, who noted the rise in new positions for compliance officers at international banks after the 1MDB scandal.

“Banks are now carrying out more enquires related to KYC (Know Your Customer) and finding out the sources of their clients’ wealth – especially those with over SG$10 million (US$7.3 million).

“These increases in compliance activities were happening as it is, but without 1MDB, they would have happened at a slower pace,” he added.

More scrutiny

While regulations and framework have always existed, Chin Yong said it was mostly left up to the banks to decide how to handle compliance issues. The level of enforcement has now increased, and more scrutiny and tighter regulations have emerged in Singapore – in part because the 1MDB scandal involved a number of Singaporean banks.

The 1MDB investigations in Singapore led to the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) closing two banks, handing out fines to eight financial institutions totalling SG$30 million (US$21.8 million) and serving lifetime prohibition orders on four people deemed unfit to re-enter the financial industry. According to Singapore’s Attorney-General’s Chambers website, more than SG$200 million (US$145.8 million) was seized as a result of the 1MDB investigations – along with the conviction of five suspects for money laundering and other offences.

Singapore’s status as ASEAN’s financial hub means it is more focused on stronger regulatory reporting regionally – especially after the US Treasury Department targeted the island state for money laundering risks last June, in part due to Singapore holding the equivalent of US$368 billion from Indonesia in its banks, or 40 percent of Singapore’s total bank deposits.

The LexisNexis Risk Solutions report pointed out that increases in alert volumes, resource costs and stress on compliance teams has led to increased costs associated with technology investment as well. For Singaporean firms, some of this investment pressure may be coming from regulatory authorities, particularly MAS which has encouraged more RegTech (regulatory technology) and use of blockchain over the past two years.

With regulatory compliance and reputational risk emerging as the top drivers of AML initiatives, the region is better equipped to prevent another 1MDB from happening again.

Related articles:

1MDB’s Jho Low charged over Obama donation