Following the conclusion of the 34th ASEAN Summit last weekend in Bangkok, Thailand, it came as no surprise that the bloc was heavily criticised for suggesting Rohingya refugees will repatriate back to Myanmar within two years.

More than 740,000 Rohingya have fled to refugee camps in Bangladesh since a 2017 army crackdown on the stateless minority. Meanwhile, the Rohingya have been largely against the idea of returning, citing safety concerns and a lack of citizenship.

A final statement from the weekend summit said ASEAN leaders supported Myanmar’s efforts to “facilitate the voluntary return of displaced persons in a safe, secure and dignified manner”. The statement did not include the term Rohingya.

The bloc has long received criticism from human rights observers who claim that ASEAN has done little to ensure the safety of the Rohingya. The assertion is that diplomacy between the 10 member countries as well as its adherence to the non-interference policy has trumped human rights concerns.

Some observers have also warned of the potential risks involved in brushing off the issue and allowing the supposed genocide to continue. In August last year, Malaysia’s Defence Minister Mohamad Sabu was quoted by the media as saying that the displaced community could easily be recruited by terrorist groups, if they are convinced the only way to achieve victory and return to their homeland is death by combat.

“This is our concern. It may happen to the Rohingya, similar to what happened to the Palestinians. When they are desperate, they can accept whatever extremist views because they feel that is their only way out.

“This is why the Myanmar issue is a big issue for Southeast Asia. It is not an internal conflict nor is it a domestic issue because their refugees have spilled over to Malaysia, Bangladesh and a few other countries,” he said on the side-lines of the International Association for Counter-Terrorism and Security Professionals (IACSP) ASEAN Security Symposium.

Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army

In May 2018, reports quoted Amnesty International as claiming that Rohingya Muslim militants in Myanmar from a group called the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) had killed 99 Hindu civilians in one, or possibly two massacres. ARSA had denied involvement.

Amnesty says interviews it conducted with refugees in Bangladesh and in Rakhine state confirmed that mass killings carried out by ARSA took place in a cluster of villages in northern Maungdaw Township at the time of its attacks on police posts in late August 2017. The findings also show ARSA was responsible for violence against civilians, on a smaller scale, in other areas.

These are not the only attacks that ARSA has committed. ARSA has also claimed responsibility for an ambush carried out on 5 January 2018 in the village of Turaing, which reportedly injured six members of Myanmar's security forces and a civilian driver.

The International Crisis Group (ICG) reported on 14 December 2016 that in interviews, the leaders of ARSA claimed to have links to private individuals in Saudi Arabia and Pakistan. The ICG also claimed in unconfirmed reports that Rohingya villagers had been "secretly trained" by Afghan and Pakistani fighters.

In 2017, ARSA leader Ataullah Abu Ammar Jununi stated in a video posted online that "our primary objective under ARSA is to liberate our people from dehumanising oppression perpetrated by all successive Burmese regimes".

The group claims to be an ethno-nationalist insurgent group and has denied allegations that they are Islamists, claiming they are secular and "have no links to terrorist groups or foreign Islamists". However, ARSA follows many traditional Islamic practices such as having recruits swear an oath on the Quran, referring to their leader as an emir (head of state), and asking for fatwas (Islamic religious decrees) from foreign Muslim clerics.

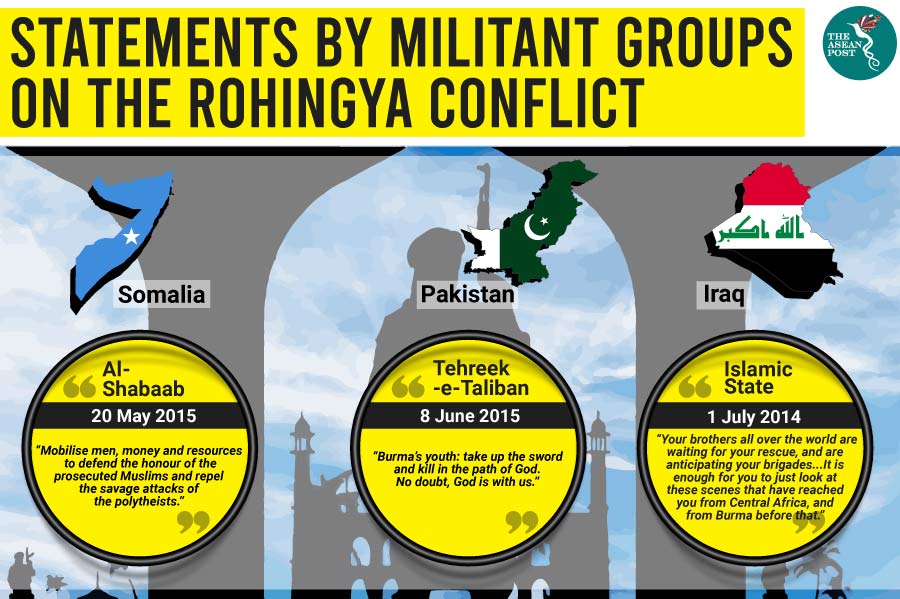

A security expert has also cited several terrorist Islamist groups as voicing support for the plight of the Rohingya as early as 2014. So, while ARSA may not have any links to terrorist groups, those links can be built fairly easily.

“There are elements of foreign terror organisations having a hand in their incitement,” JK Associates Principal Consultant Khen Han Ming told The ASEAN Post.

What makes the matter worse, according to Khen, is that there doesn’t seem to be any end to the plight of the Rohingya in sight. With military operations still outside civilian control in Myanmar, and no strong voices in support of the Rohingya in the elected government anyway, the Tatmadaw will continue to prosecute their counter-insurgency to whatever extent they wish. International pleas for moderation, he said, are unlikely to be heeded.

“Unlike their peace deals with the Karen or Kachin rebels in the 1990s and 2000s, there’s no end game. There isn’t even the most rudimentary plan to incorporate the Rohingya into Myanmar society as there is or has been for other ethnic rebel groups.

“The grim plight of the Rohingya may be entering perhaps its darkest phase yet.”

There are real dangers associated with allowing the alleged oppression against the Rohingya to continue. Several experts have already predicted that if left unattended the region will come face to face with a very serious problem. ASEAN is best suited to address this urgent matter and it should do so quickly and seriously. Continuing to not do so may become one of the biggest regrets the region will have to live with.

Related articles: