Myanmar’s garment industry has cemented itself as an important engine of sustainable development, with the country now the region’s latest hub for low-cost clothing.

With minimum wages lower than China, Cambodia and Vietnam – all neighbouring countries with established garment manufacturing sectors of their own – Myanmar has attracted orders from international retailers such as Adidas, Gap, H&M and Marks & Spencer.

Leading the country’s manufactured goods export sector, Myanmar’s garment exports rose from US$349 million in 2010 to nearly US$4.6 billion last year – making up around 10 percent of the country’s export revenues.

However, this strong growth is at risk due to several factors.

As the International Labour Organisation (ILO) notes, owing to its recent history – Myanmar was under military rule from 1962 to 2011 – the country is yet to develop an efficient legal and institutional framework to establish sound labour market governance.

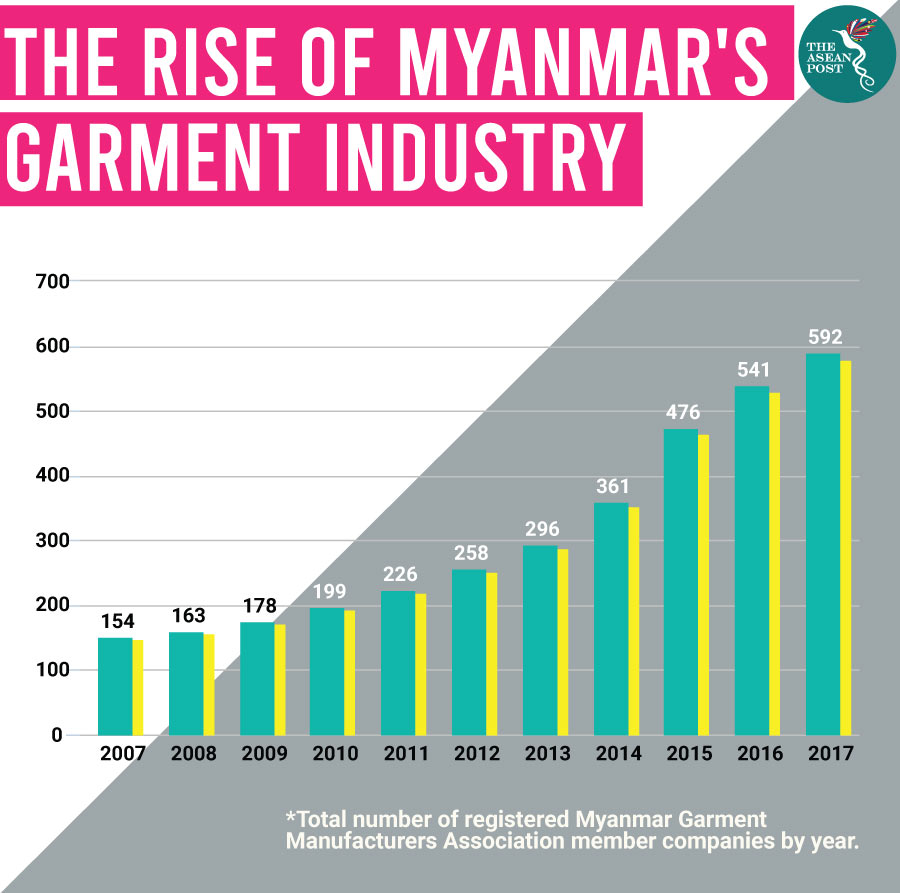

The Myanmar Garment Manufacturers Association estimates that its nearly 600 member factories provide jobs for approximately 450,000 workers. The majority of these workers are young women, which is why their empowerment is vital.

An ILO report in January titled ‘Weaving Gender: Challenges and opportunities for the Myanmar garment industry’ found that there were limited opportunities for women already working in the sector to learn new skills or to seek a promotion. Some evidence of sexual harassment was found in most of the 16 factories the ILO surveyed for the report, which also concluded that factories generally lack formal policies and processes to effectively identify and address workplace harassment and abuse.

“As there is a clear relationship between creating more inclusive and safe workplaces for workers and overall productivity, developing sound workplace practices is clearly an area where workers and employers can find common agreements. Trade unions at factory level can significantly contribute to creating this positive environment,” stated U Thet Hnin Aung, Secretary General of the Myanmar Industries Crafts and Servicer (MICS).

A Myanmar trade union grabbed international headlines in October when alleged unfair dismissals at the Chinese-owned Fu Yuen Garment Co. Ltd factory in Yangon last October led to nearly two months of strikes that culminated in clashes with a group of people a protest leader said were “hired thugs”.

The factory workers said they set up a union to address concerns about abuse from managers, limited toilet breaks and unbearably hot working conditions. While most of these complaints were resolved, Fu Yuen’s refusal to re-hire the 30 workers who organised the strike after being dismissed for allegedly disrupting production and violating company rules led to more protests – and the eventual clash with the armed mob which left dozens injured.

EBA privileges

Gender empowerment and freedom of association aren’t the only issues Myanmar’s garment sector are facing.

The European Union’s (EU) potential withdrawal of its Everything But Arms (EBA) trade preference scheme has cast an even bigger shadow over the industry, especially with 60 percent of Myanmar’s garment exports heading to the bloc.

The EBA trade privilege provides the world’s least developed countries with tax-free access to vital EU markets for their exports except for arms and ammunition, although such preferences can be removed if countries fail to respect core United Nations (UN) and ILO conventions.

Allegations by UN investigators of grave human rights violations in Rakhine, Kachin and Shan states, and concerns about labour rights, has led the EU to review Myanmar’s access to the European market.

The EU concluded a second monitoring mission to Myanmar to gauge progress on human and labour rights in February, with European Union Trade Commissioner Cecilia Malmström telling media this month that while the formal procedure of revoking the EBA privilege has not been initiated yet, the EU has warned Myanmar that it could be.

Myanmar are not the only ones in hot water over EBA privileges, and fulfilling the EU conditions will take far more political will than addressing personal safety and gender equality – both short-term targets that can be resolved internally.

It took almost five years for Myanmar to draft a law that criminalises violence against women, but the garment sector cannot afford to turn a blind eye to workplace sexual harassment policies for that long. And although trade unions have the right to organise strikes in Myanmar, heavy handed tactics to deal with protests will only paint the garment industry in an even more negative light.

Failure to address these issues will no doubt severely hurt the immense potential of one of Myanmar’s rare economic success stories.

Related articles: