The lack of transparency surrounding plans to construct dams on the Tanintharyi River in southern Myanmar, and the impact it will have on the livelihoods of the Karen – the area’s indigenous people – is set to add more tension to an area already filled with strife.

While there are 18 Memorandums of Understanding (MoU) for dams on the Tanintharyi River – one of southern Myanmar’s largest free-flowing waterways – local communities have received no information on their location, size or status according to a report by three civil society groups last week; Candle Light Youth Group, Southern Youth and Tarkapaw Youth Group.

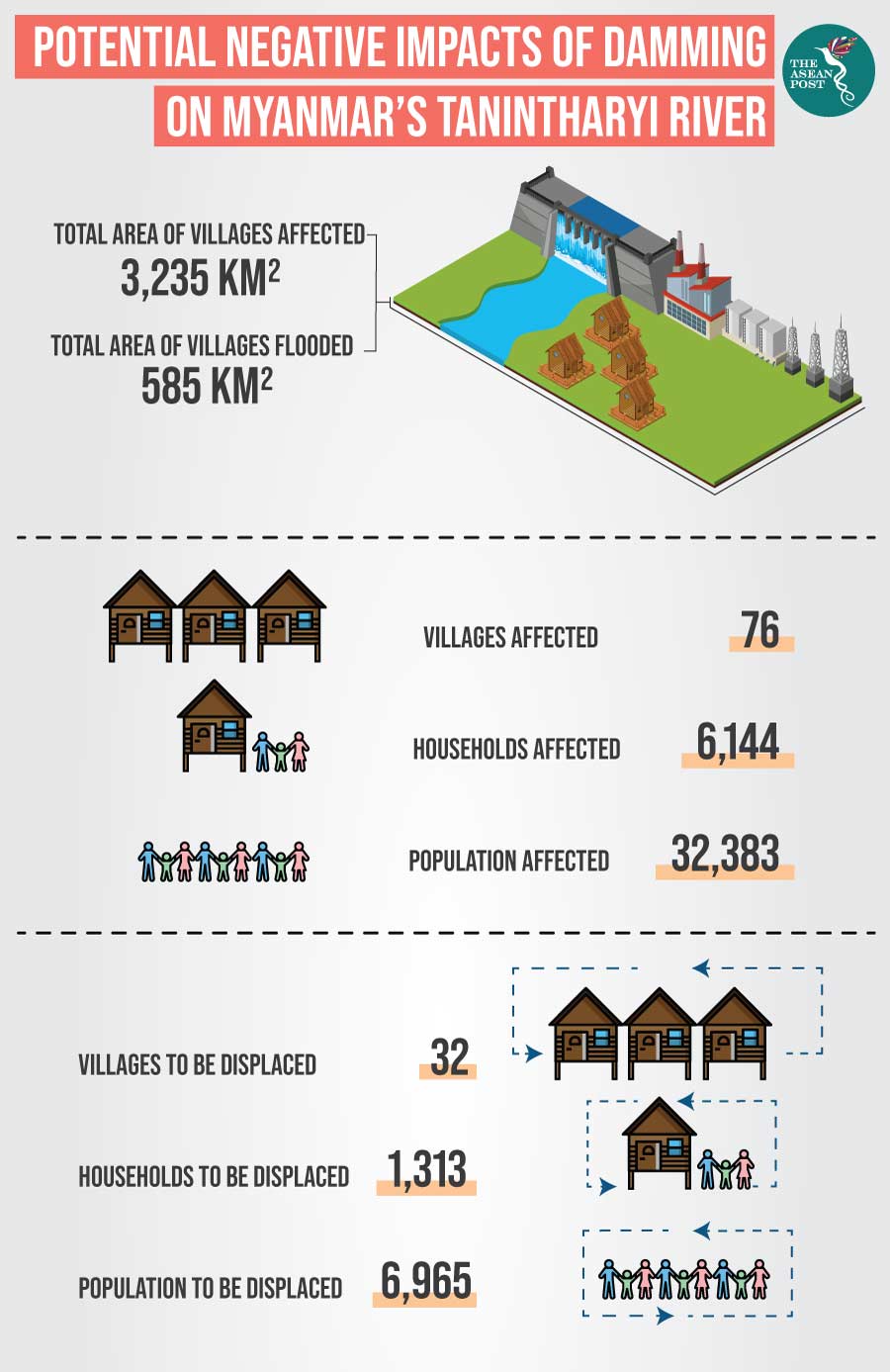

The report titled ‘Blocking a Bloodline: Indigenous Communities along the Tanintharyi River Fear the Impact of Large-Scale Dams’ also notes that 32,008 people from 76 villages living directly along the river depend on it as a vital source of food, water, transportation and cultural expression – all of which are at risk due to plans to build a 1,040 megawatt (MW) hydropower project by Thai-owned Greater Mekong Sub-region Power Public Co Ltd (GMS).

The dam would submerge an area of 585 square kilometres of community owned farms and forestland, forcing nearly 7,000 people in 32 upstream villages to relocate – destroying rich aquatic ecosystems and habitats as well as inundating some of Southeast Asia’s largest remaining areas of forest and biodiversity according to the report which was based on interviews with more than 1,200 people who live along the river.

Armed conflict

Adding to the issue’s complexity is the fact that the area has seen more than six decades of civil war between the Karen National Union (KNU) and the government of Myanmar, which has forced 80,000 people to flee their homes to hide in forests or refugee camps along the Thai border. While local populations have slowly returned since a 2012 ceasefire, communities are fearful that the construction of dams along the river will lead to a return to armed conflict – especially with the KNU withdrawing from peace discussions in 2018.

As the International Finance Corporation (IFC) – a sister organisation of the World Bank – noted in a 2017 report titled ‘Strategic Environmental Assessment of the Hydropower Sector in Myanmar’, the predominant mode of hydropower development under former administrations – the so-called legacy model – has worsened ethnic minority grievances against the state and contributed to staunch public opposition to hydropower development, with case studies from Kachin, Shan, Kayah and Karen states serving as examples of past abuses which have resulted in community grievances.

“This legacy model of hydropower fuels wider ethnic minority grievances regarding social and environmental injustices, limited opportunities for decision-making and benefit in geographies of hydropower development,” stated the report. “The legacy model – which has at times required military clearance operations and forced relocations – is associated with an increased risk of armed conflict, displacement and abuse of populations, and land mine contamination.”

Foreign interests

Initial assessments for a dam on the river were conducted as far back as 1998 by Japan’s Nippon Koei Company. A decade later, the Italian-Thai Development (ITD) Company signed an MoU with Myanmar’s Ministry of Electric Energy (MOEE) to develop a dam on the river – although nothing came of both plans. While the list of 18 companies which plan on building hydropower dams on the river is not publicly available, there is no doubt they are all eager to capitalise on the country’s hydroelectric generating potential – and to a lesser extent, the vastly unmet local demand for energy.

Myanmar has the lowest grid connected electrification rate in Southeast Asia with only around 40 percent of the country’s population of 55 million people enjoying access to reliable electricity. The IFC estimates that Myanmar will require at least 500 MW of additional generation capacity to come online annually if the country is to meet its goal of 100 percent electrification by 2030.

With its numerous environmental and social costs, hydropower may not necessarily be the best option for Myanmar – which recently launched its first commercial solar plant to widespread praise. Touted for its cost-effectiveness, low maintenance costs and reduced emission levels, solar power may be a more socially inclusive source of renewable energy for Myanmar.

However, with Myanmar a major regional energy exporter, most of the electricity it produces is bound to be headed for countries like China and Thailand.

The government’s own 2015 Master Energy Plan even notes that energy importing countries “receive many of the positive political and economic impacts of hydropower” while communities living in the vicinity of hydropower sites may “remain without electricity and have other elements such as food, water or livelihood undermined”.

Such glaring inequalities only add to the existing mistrust that communities along the Tanintharyi River have for the authorities. Unless alternative paths of development are explored, plans to build dams on the river are sure to be met with even more resistance.

Related articles:

ASEAN’s shrinking biodiversity