With 7.7 billion humans inhabiting our crowded planet, forests have mostly disappeared, animal species have gone extinct and the Earth’s atmosphere keeps getting dangerously warmer by the day. The number of humans is expected to grow to nine billion people by 2050 and reach 11 billion by 2100, according to the United Nation’s (UN) 2019 World Population Prospect report. Further population growth will only create a future of increasing poverty, acute food shortages, conflicts, and environmental degradation.

But, authors of the book, ‘Empty Planet: The Shock of Global Population Decline,’ say that the current outlook with regards to overpopulation is wrong. John Ibbitson and Darrell Brick argue, citing other researchers, that the global population is heading for a steep decline, bringing a new set of challenges. Based on other statistics from the UN 2019 World Population Prospect report, the world is already facing a low fertility rate that is expected to fall further to the point where no country is expected to have a fertility rate of more than five births per woman by 2050.

Two children are enough

Indonesia, the world’s fourth-largest country in terms of population size, is expected to grow from a population of 260 million to 311 million by 2045. This projection is based on data from Statistics Indonesia's (BPS) 2018 report, ‘Indonesia Population Projections 2015-2045’. National Development Planning Minister Bambang Brodjonegoro said that to hit 311 million people, there must be an average of two children per family and an infant mortality rate of three percent per year.

Once the population reaches 311 million, the country will have an ageing population, as the percentage of the elderly will reach 19.8 percent for the entire country. An ageing society will lead to other challenges ahead.

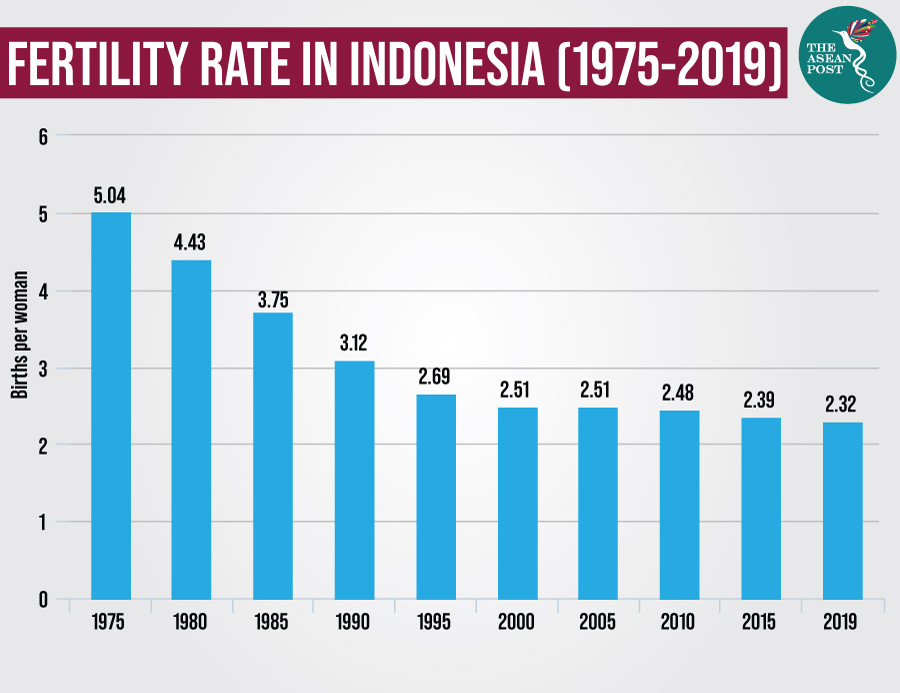

In the 1970s, Indonesia’s National Population and Family Planning Board (BKKBN) was launched to address the population boom. The BKKBN had two goals – to establish a “small, prosperous family” as the norm in Indonesia and to reduce fertility through the promotion of contraceptives. At the time, Indonesia had a five percent contraceptive prevalence rate (CPR) and a 5.6 total fertility rate (TFR).

The BKKBN’s family planning efforts and ‘two children are enough’ campaign achieved remarkable results. In 2000, the TFR dropped by 54 percent, from 5.6 births per woman to 2.6. The country now boasts a 61 percent CPR and 2.3 TFR. The nation’s target of a replacement-level fertility rate of 2.1 births per woman by 2025, to stabilise its population growth, is within grasp.

Critical planning

Effective family planning not only addresses the challenges posed by a growing population, but it is critical for a healthy, stable, and prosperous future. Family planning empowers women to make informed decisions about their bodies and to actively exercise their rights to health, wellbeing and education among others.

It is easier for married women to have access to different types of contraceptives in Indonesia today. “In our efforts to achieve the desired [total fertility] rate, the BKKBN has striven to improve access to and the quality of health and contraceptive care services in areas across the country,” said the agency’s family planning and reproductive health division deputy head, Dwi Listyawardani.

The BKKBN revealed that religious leaders played an important role in promoting family planning in an otherwise conservative country. Major Muslim organisations such as Nahdlatul Ulama and Muhammadiyah advocated for family planning and the use of contraception, saying that the two were allowed in Islam as they allowed Muslims to create prosperous families and strong successors.

The BKKBN’s director of international training and collaboration, Hermansyah, said that “Muslim religious leaders in Indonesia are very cooperative in promoting the program, so it can run smoothly here.” Still, some Muslim religious leaders have banned family planning programs and contraception.

Nonetheless, the downtrend in the TFR is perhaps due to the nation’s awareness and understanding of contraception. According to a PMA2020 survey in 2017, approximately 32 million women are current users of modern contraception in Indonesia. The PMA2020 generates data on an array of health and development indicators. The government is committed to adding at least 700,000 additional users of modern contraception annually until 2020.

Unfortunately, access to contraception is not extended to young women, married or otherwise. UNICEF reports that 1,408,000 Indonesian women aged between 20 to 24 were married before the age of 18, while 50,000 girls under 15 still marry in Indonesia each year. Besides the issue of child marriages, the number of girls without access to contraception is high. Based on data from the Indonesian Demographic Health Survey (SDKI), in 2017, only 45 percent of married girls (15 to 19 years old) who wished to delay or prevent pregnancy, used a modern contraceptive method.

Indonesia has one of the highest rates of unplanned pregnancies across all of Asia and unplanned pregnancies have been known to undermine opportunities for education and employment, exacerbate poverty and perpetuate gender inequity.

While efforts are already underway to increase awareness of family planning’s paramount importance, Indonesia must also address gaps in reproductive health services, including access to contraception for young women. When families, of all ages, are given the choice to plan, maternal and child health improves, women participation in labour increases and population growth stabilises.

Related articles: