Half a million Cambodian farmers could possibly be looking at empty rice bowls if the European Union (EU) pushes through with the withdrawal of its Everything But Arms (EBA) trade preference.

While the garment and footwear sectors stand to lose the most if the EBA trade scheme – which gives 49 of the world’s least developed countries tax-free access to vital EU markets for all exports except for arms and ammunition – is removed, Cambodia’s rice industry could be staring at tough times ahead.

Already forced to deal with a historic drought and the reintroduction of an EU tariff on rice which has cut exports to Europe in half, Cambodia’s rice farmers now also have to worry about the possibility that that EBA duty-free preference will be suspended following the EU’s concerns about political freedom, human rights and labour rights.

In a statement released on Thursday, the Cambodian Rice Federation (CRF) noted that the duties imposed on Cambodian rice in January has been “acutely felt by most of the 500,000 families in Cambodia who eke out a living farming jasmine and fragrant long grain rice”. This is in spite of the fact that these varieties are geographically specific and do not compete directly with products grown in the EU.

“As if this weren't painful enough, the EU is now considering the withdrawal of its EBA program. EU legislators are threatening to end the arrangement to press for policy reforms in Cambodia,” said the federation.

“A political thrashing could lead to a virtual threshing of an industry and a way of life (and) the CRF appeals to the EU to save the livelihood of half a million families and to save the work that we have done to earn your respect…”

EBA’s importance

The EBA has eased the movement of goods from Cambodia to Europe since 2003, providing a secure platform upon which an entire economy has been able to embrace growth and prosperity in an increasingly demanding world market.

The EU is Cambodia’s second largest trading partner after China, and Cambodia’s exports to the EU totalled €5.3 billion (US$5.47 billion) last year – more than a third of its total exports – with garment and footwear making up the majority of that sum. Crucially, over 95 percent of Cambodia’s exports to the EU took advantage of EBA preferences.

In May, the World Bank estimated that Cambodia’s exports to the European market could decline by US$654 million a year if the EBA trade preference was suspended.

The EU in February started an 18-month process that could lead to the EBA’s suspension in Cambodia. In June it (the EU) sent a monitoring mission to Cambodia which noted the steps the country was taking towards improving compliance with international standards on freedom of association and collective bargaining, as well as in addressing a number of land disputes in relation to economic land concessions.

The EU is expected to produce a report based on its findings and conclusions this month, and Cambodia will have one month to reply.

EU tariff on rice

As it is, Cambodia’s rice farmers are already feeling the pinch from the re-introduction of EU import duties on rice in January.

Complaints from Italian and Spanish farmers that they were being undercut led to an European Commission (EC) investigation, which confirmed that increases in imports of rice from Cambodia and Myanmar were causing economic damage to European rice producers.

As a result, the EU slapped import duties on rice from both these countries. Starting from €175 (US$195) per ton this year, it will be reduced to €150 (US$167) per ton in 2020 and €125 (US$139) per ton in 2021.

The CRF listed prices ranging from between US$475 - US$485 per ton for long grain white rice, US$790 - US$805 per ton for fragrant rice and US$1,035 - US$1,045 per ton for jasmine rice – with January’s tariffs effectively pricing Cambodian rice out of the EU market.

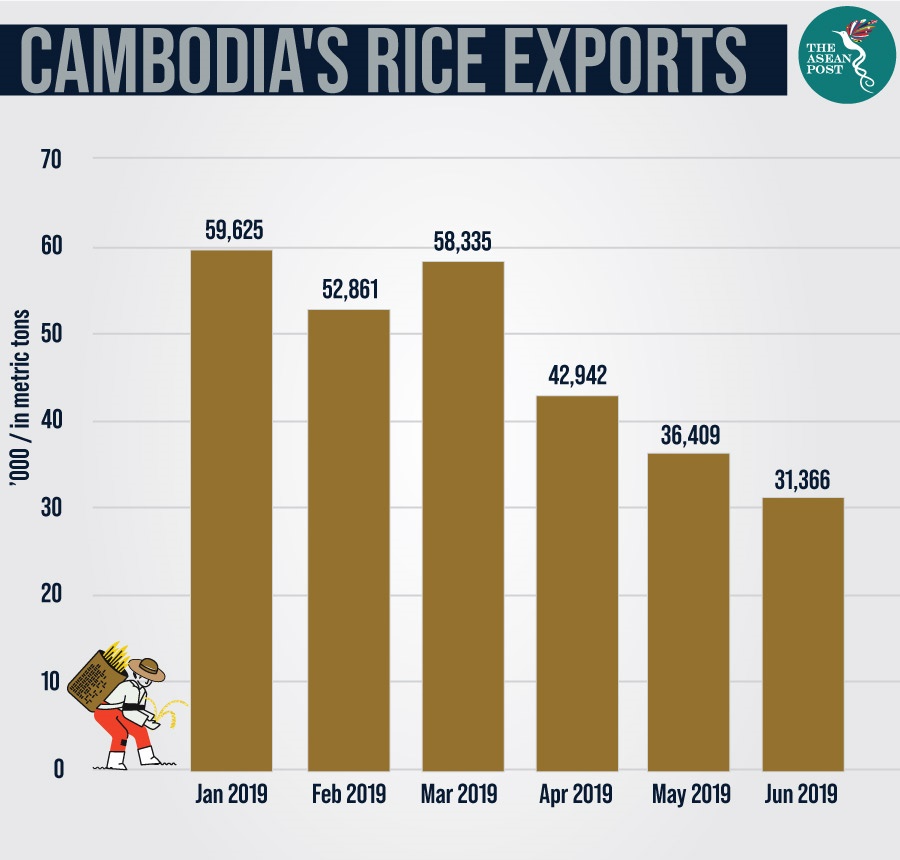

Cambodia exported more than 93,000 tons of rice to the EU In the first six months of 2019 – almost half the amount exported during the same period in 2018.

Chinese connection

Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen has assured the Cambodian public that staunch ally China would come to their aid if the EU withdraws its EBA trade scheme, declaring in March that it “won’t make us dead.”

China has already agreed to import 400,000 tons of Cambodian rice this year – up from 300,000 tons last year – and Cambodian government data shows that rice exports to China have risen 66 percent in the first half of 2019 to 118,401 tons.

Regional observers will no doubt be wary of the implications that Cambodia’s increasing reliance on China will have.

It is perhaps naïve to expect China to make up for all EBA-related losses after only importing US$355 million from Cambodia’s two key export industries – garment and footwear – in 2017 according to World Bank data.

China is already Cambodia’s largest creditor and the single biggest source of foreign direct investment (FDI), and Cambodia’s overdependence on China – or any other one country for that matter – should be cast aside for a more multilateral approach to secure economic diversification.

Related articles: