Metro Manila has been found to be the most congested city in developing Asia after a study of 278 cities to measure citywide congestion by the Asian Development Bank (ADB).

Congestion arises when demand for travel exceeds the transportation network’s maximum capacity, and the pollution that comes along with it are important issues faced by city planners in ASEAN and abroad.

An urban sprawl of 17 cities characterised by outdated infrastructure, a booming economy and an increasing population, Metro Manila’s traffic jams have left even Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte at a loss – saying in February that solving the problem was the only campaign promise he had failed to deliver.

Congestion has been so bad in Metro Manila – an area of more than 12 million people – that Duterte signed the Telecommuting Act in January to allow private sector employees to work from home, a move aimed at improving Filipinos’ work-life balance.

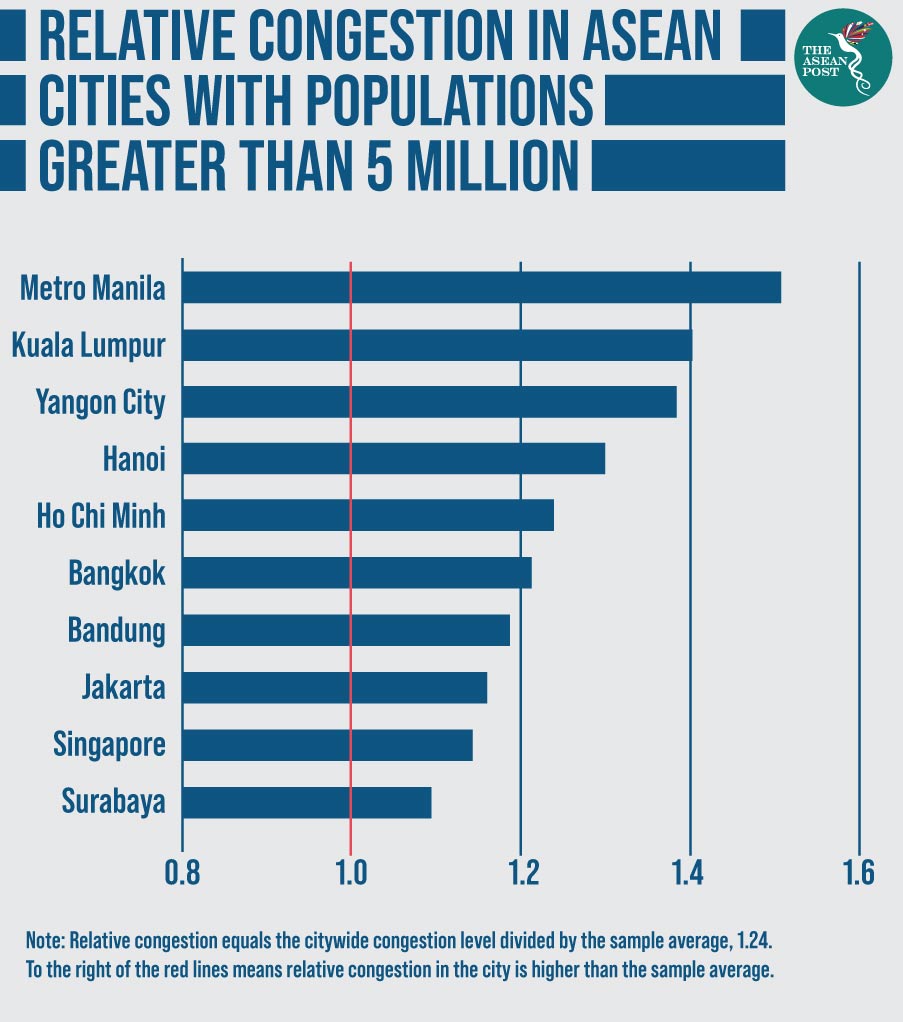

The study by the Manila-based ADB noted that the average citywide congestion across the 278 cities studied was 1.24, which means that 24 percent more time is needed to travel during peak hours than during off-peak hours.

Metro Manila’s congestion index was calculated to be 1.5 – with Malaysia’s Kuala Lumpur coming in second with a congestion index of 1.4 and Myanmar’s Yangon third with a congestion index of 1.38.

All these traffic jams come at a cost.

In Metro Manila, the daily economic impact of the loss was calculated to be 3.5 billion pesos (US$67.4 million) in 2017 according to the Japan International Cooperation Agency. In 2012, the figure was 2.4 billion pesos (US$46.3 million).

“How long does it take you to get (to places) from wherever you live?”, ADB’s Director for Macroeconomics, Economic Research and Regional Cooperation, Abdul Abiad, asked Filipino media during a press conference on Wednesday.

“If you think about people commuting for an hour or two each way every day, think about the lost productivity.

“Build public transport ... and make developments walkable, and have easy access to transport,” he said of a possible cure for Metro Manila’s congestion.

However, it is not that simple.

Complex issue

While successful cities undoubtedly need an efficient multimodal public transport system which combines subways, trains, buses, ride sharing and less formal services like autorickshaws and jeepneys – combined with a push for cleaner fuels and greener technologies – there are other factors at play.

An increase in public transport facilities does not necessarily mean less congestion. A 2016 study by two researchers from Vietnam’s Ton Duc Thang University and the Vietnamese German University identified several other variables which contributed to the peoples’ decision to use public transport in Ho Chi Minh City – the country’s largest urban area.

Titled ‘Encouraging Public Transport Use to Reduce Traffic Congestion and Air Pollutant - A Case Study of Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam’, the study by Thi Phuong Linh Le and Tu Anh Trinhb noted that convenience, travel distance, travel cost, income, marital status, number of children, social norms and safety all played vital roles in choosing a means of transport.

“Although the public transport system has been improved in terms of on-board services and bus fleet, still the proportion of the migrant student and employee users is limited,” they pointed out.

“This reveals that students and employees have not had a friendly attitude towards bus services, and the motor vehicle is still their highest priority for travelling,” they added in the report.

As the ADB noted, it is possible that increasing road capacity when public transport is improved induces additional driving, thereby pushing congestion back to where it was before improvements were made.

Evidence on the actual impact of public transportation on congestion is mixed, and researchers in the United States (US) have found evidence that improving public transport does not necessarily reduce congestion in US cities.

While expanding rail mass transit reduced congestion, expanding bus services did not. However, US cities many not be the best to draw parallels with those in developing Asia.

Cities in developing Asia are generally more populous, denser, and focused on a single urban core, rather than distributed over several hubs in an urban area, as is the case in the US. Car ownership numbers in developing Asia, although rising, are still lower than in the US.

Back in the Philippines, citizens are looking forward to the impact that Duterte’s Build! Build! Build! initiative will have on improving mobility.

A massive infrastructure modernisation programme costing US$180 billion, most of its 75 projects relate to transport and include a new Manila airport terminal, the capital’s first subway system and a railway in Mindanao.

However, as locals have been quick to point out, most of these new developments are unsurprisingly leading to even more traffic jams.

Related articles:

Jokowi wants Jakartans to use public transport

Manila's traffic jams costing lives

Can Duterte’s “Build! Build! Build!” boost the Philippines’ economy?