Lao human rights activist, Od Sayavong, has been missing in Thailand since late August, just months after meeting a United Nations (UN) special rapporteur.

Od, a former member of “Free Lao” was last seen at his home in Bangkok on 26 August. On 2 September, a colleague reported his disappearance to the Thai police. To date, authorities have not provided information as to his whereabouts.

On 7 September, Human Rights Watch (HRW) expressed concern regarding possible foul play in Od’s disappearance. They accused the Lao government of arbitrarily arresting and detaining activists and those deemed critical of the government.

Lao’s penal code effectively allows for the prosecution of dissidents with harsh prison sentences. Anti-government propaganda is punishable by up to five years imprisonment and journalists who fail to file “constructive reports” or who seek to “obstruct” the work of the government may be given up to 15 years.

But it isn’t just Lao’s communism-endorsing laws that have human rights advocates worried. There have been numerous instances where Thai authorities have collaborated with foreign governments to arrest and forcibly return exiled dissidents in violation of international law. According to HRW, this has included people formally registered as persons of concern by the UN refugee agency, adding that some countries, including Lao, have allegedly reciprocated by turning a blind eye to the enforced disappearance and murder of Thai dissidents seeking asylum in their territory.

In January, the media was abuzz with news of 18-year-old Saudi woman, Rahaf Mohammed al-Qunun, who barricaded herself in her hotel room for fear that Thai immigration officials gathered outside her door would force her on to a plane to leave the country. Qunun maintained she would be killed if she was returned to Saudi Arabia after having denounced Islam, and said she would not leave until she could see the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

Prior to that, in 2015, Thailand forcibly repatriated over 100 Uighurs back to China. The decision elicited a backlash from the United States (US), the UN and international advocacy organisations who claimed that the Uighurs would be tortured – or worse – after their return. Thailand insisted that it simply lacked the means to let them stay.

Throughout the years, Thailand has also been known to repatriate Myanmar refugees seeking asylum in the country.

You scratch my back, I scratch yours

HRW has claimed that in reciprocation to Thailand’s supposed habit of repatriating asylum seekers, some countries, including Lao, have turned a blind eye to the enforced disappearance and murder of Thai dissidents seeking asylum in their territory.

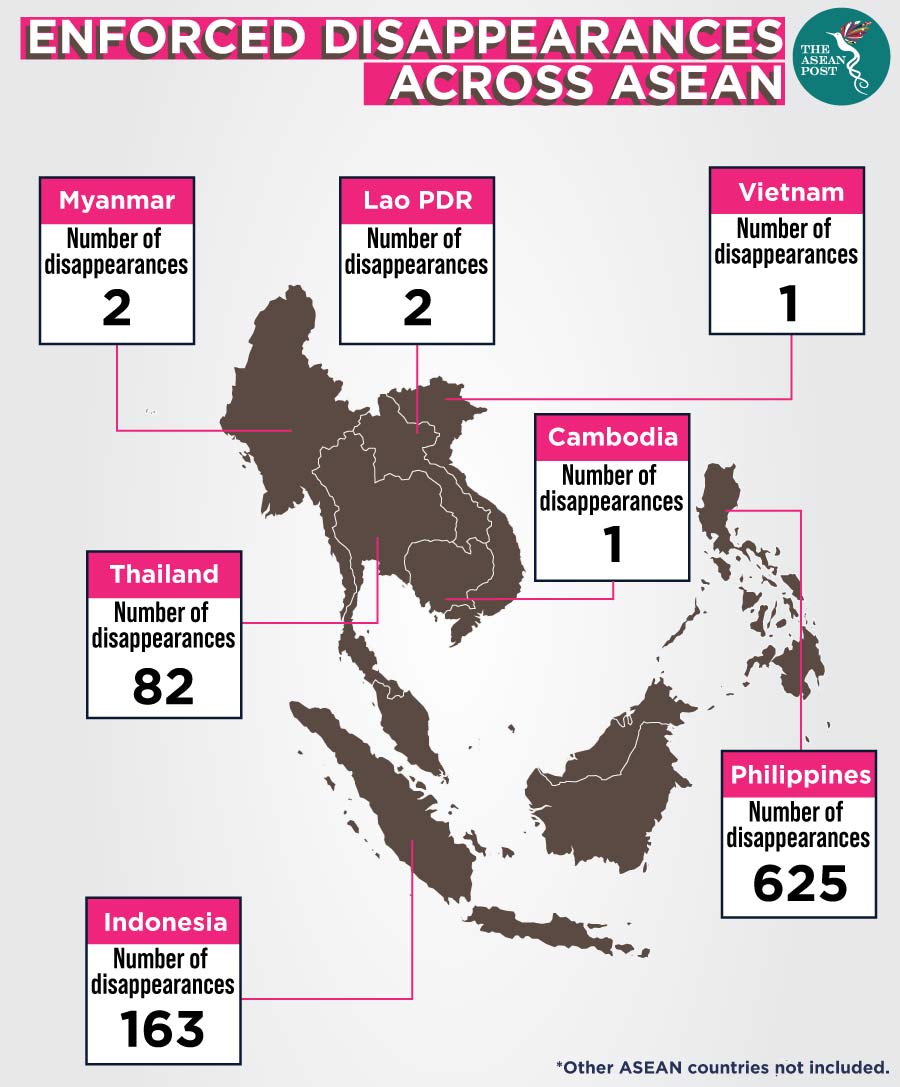

This certainly pairs up with the allegation that there have been numerous enforced disappearances in Thailand. The United Nations Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances recorded 82 cases of enforced disappearances in Thailand since 1980, including that of prominent Muslim lawyer Somchai Neelapaijit in March 2004. HRW, however, believes the actual number is higher, saying that some families of victims and witnesses remain silent, fearing reprisals by the authorities if they speak out.

So, was Od another victim of allegedly corrupt ASEAN diplomacy? If so, when and how will the practice end? ASEAN must ensure a stricter adherence to the protection of human rights from its fellow members but in order for this to happen, ASEAN must take a careful look at its non-interference policy. But that is a whole different story.

“Free Lao” is a loose network of Lao migrant workers and activists in exile based in Bangkok and neighbouring provinces who peacefully advocate for human rights and democracy in Lao. Od and other group members have occasionally held peaceful protests outside the Lao embassy and the UN headquarters in Bangkok. They have also organised human rights workshops for Lao migrant workers in Thailand.

In the article published by HRW on 7 September, the human rights group noted that members of “Free Lao” had said that they have been put under surveillance and intimidated by Thai and Lao authorities. They believed this was to stop them from protesting or otherwise criticising the government of Lao during the ASEAN People’s Forum held in Bangkok from 10 to 12 September.

Related articles: