Nutrition is central to the growth, cognitive development, school performance and future productivity of children.

However, traditional and indigenous foods are slowly being cast aside in favour of modern diets that are low in nutrients and fibre but high in sugars and fats.

Combined with busy lifestyles and budgetary concerns, malnutrition is taking a toll on a sizable portion of ASEAN children.

A report yesterday by UNICEF, the United Nations’ children’s agency, warns that millions of children in the region are unhealthily thin or overweight thanks to poor diets and processed food.

“Despite all the technological, cultural and social advances of the last few decades, we have lost sight of this most basic fact: If children eat poorly, they live poorly,” said Henrietta Fore, UNICEF’s Executive Director.

“Millions of children subsist on an unhealthy diet because they simply do not have a better choice. The way we understand and respond to malnutrition needs to change: It is not just about getting children enough to eat; it is above all about getting them the right food to eat. That is our common challenge today.”

Stunted Growth

On top of the list of such challenges is stunting – which is used to describe children who are too short for their age. As UNICEF noted in the report titled ‘State of the World’s Children 2019: Children, food and nutrition’, stunting is a stark sign that children in a community are not developing well, physically and mentally, particularly in the first 1,000 days.

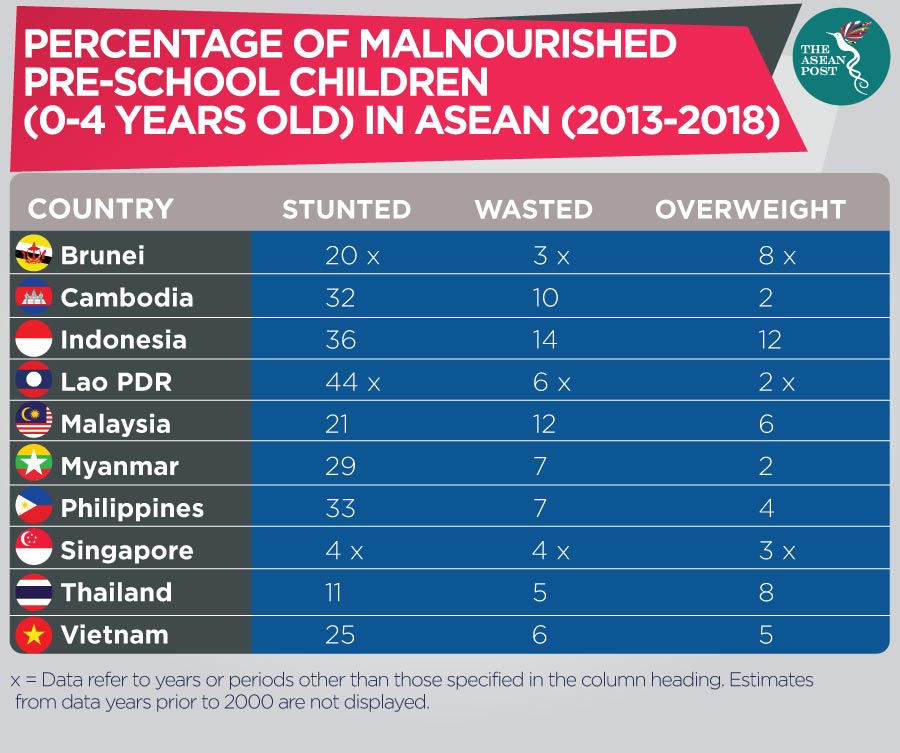

In ASEAN, the percentage of children under five who suffer from stunting range from four percent in Singapore to 44 percent in Lao PDR – with the regional average coming up to around 26 percent, or one in four children.

Stunting has been described as not just the “best overall indicator” of children’s well-being, but also an “accurate reflection” of inequality in societies.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) explains that stunting is the result of long-term nutritional deprivation and often results in delayed mental development, poor school performance and reduced intellectual capacity.

A child’s poorer school performance results in future income reductions of up to 22 percent on average, and as adults, they are also at increased risk of obesity, diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

Changing Habits

Such diseases have been on the rise across the region as economic forces have seen a steady stream of ASEAN citizens relocating to urban areas, where they often succumb to unhealthy eating patterns amidst a lack of time or money.

Not only do urban areas provide better access to education and healthcare services, they also offer supermarket chains stocked with a variety of food. While cheap and convenient, not all of them are entirely nutritious.

And because some of these foods – such as instant noodles, biscuits or crackers – can be very filling, they can reduce a child’s appetite for more nutrient-dense fruits and vegetables, which can then lead to weak immune systems, poor sight and hearing defects.

UNICEF noted a study it had conducted in which children under the age of two who were found to be getting on average a quarter of their energy intake from items such as biscuits, instant noodles and juice drinks were shorter than their peers.

‘I Am Able To Provide Only Rice’

Poverty plays a huge role in food choices, and some low-income communities which depend heavily on staples such as grains may not be able to afford more nutrient-rich items such as fruits, vegetables, meat, fish, eggs and dairy products.

“I do not think about that (healthy and balanced food),” said Noor, a Malaysian mother who was mentioned in the UNICEF report.

“Others are eating fish, but I am able to provide only rice. I know it’s not good, but that’s all I can provide,” she added.

Such families often find that instant noodles are a cost-effective and convenient way to put food on the table, and while it has long been derided for its lack of nutrients and high salt and fat content, Southeast Asians are hooked on instant noodles.

Four ASEAN countries are among the world’s top-10 consumers of instant noodles, with Indonesia the world’s second-biggest consumer behind China with 12.5 billion servings last year according to the World Instant Noodles Association.

Vietnam was fifth with 5.2 billion servings in 2018, with the Philippines seventh (3.98 billion servings) and Thailand ninth (3.46 billion servings).

Solutions

To address the growing malnutrition crisis, UNICEF has issued an urgent appeal to governments, the private sector, donors, parents, families and businesses to help children grow healthy by empowering families, children and young people to demand nutritious food.

This includes improving nutrition education and using proven legislation – such as sugar taxes – to reduce demand for unhealthy foods.

Driving food suppliers to incentivise the provision of healthy, convenient and affordable foods as well as building healthy food environments for children and adolescents by using proven approaches – such as accurate and easy-to-understand labelling and stronger

controls on the marketing of unhealthy foods – are other steps stakeholders can take to combat malnutrition.

At the end of the day, all stakeholders – be it governments, the private sector or civil society – need to take a concerted effort to prioritise child nutrition and work together to address the causes of unhealthy eating in all its forms.

Related Articles: