As media practitioners across the world gather tomorrow to commemorate the International Day to End Impunity for Crimes against Journalists, reporters in the Philippines have little to celebrate.

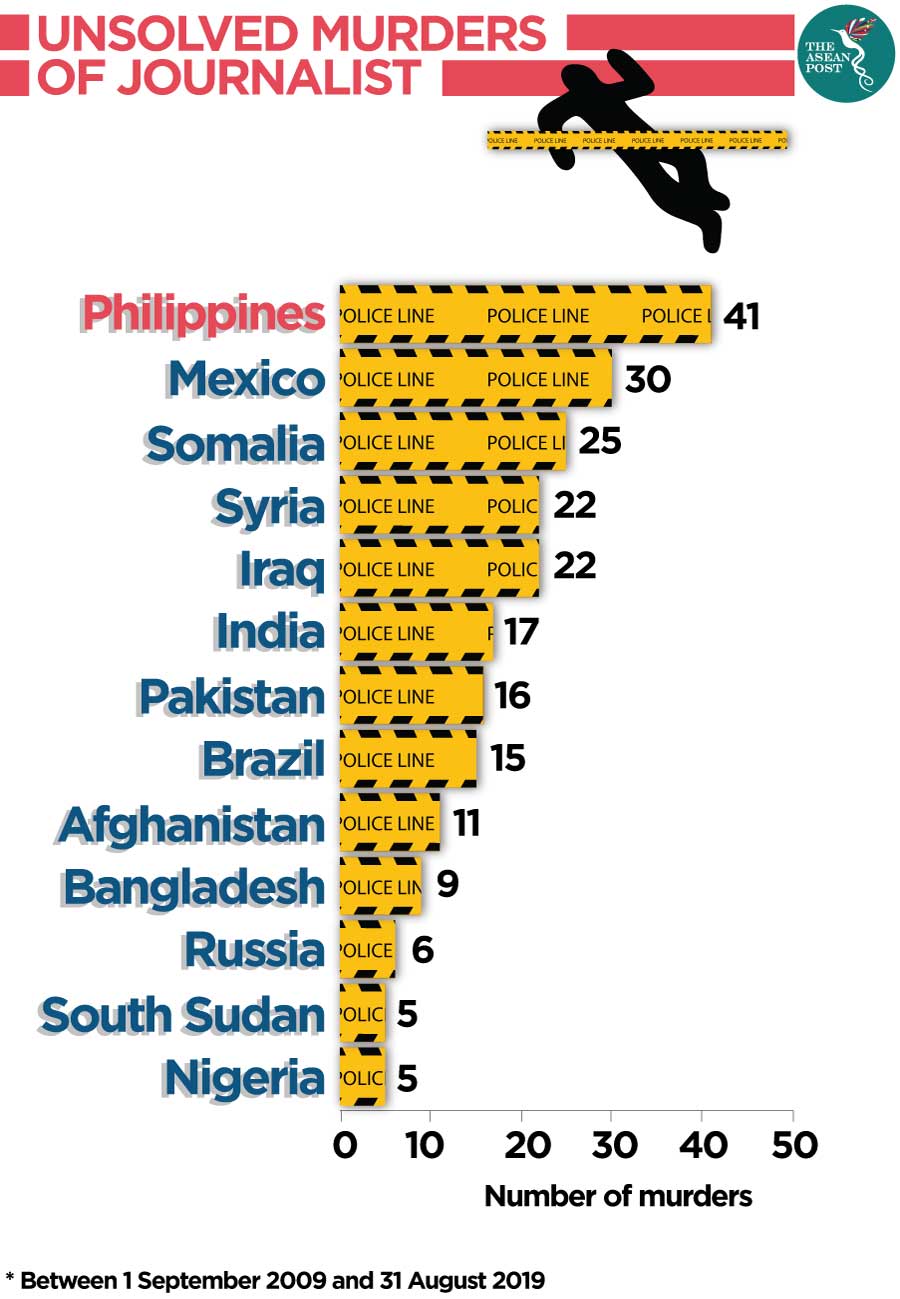

For the third year in a row, the Committee to Protect Journalists’ (CPJ) Global Impunity Index has named the Philippines as the country with the most unsolved murders of journalists, with perpetrators of 41 killings over the past 10 years yet to be served justice.

The Philippines was second to Iraq from 2008 to 2017, topping the chart in 2017 with 42 unsolved murders and again in 2018 with 40 unsolved murders. Mexico is second this year with 30 unsolved killings, followed by Somalia (25), Syria (22) and Iraq (22).

Across the globe, a total of 318 murders of journalists remain unsolved in the last 10 years according to the CPJ, with many of the cases linked to war and civil unrest.

“The 13 countries that make up the list of the world’s worst impunity offenders represent a mix of conflict-ridden regions and more stable countries where criminal groups, politicians, government officials, and other powerful actors resort to violence to silence critical and investigative reporting,” the CPJ report stated.

The CPJ are not alone in highlighting the Philippines’ failure to attain justice for unsolved murders of journalists, with last year’s International Federation of Journalists (IFJ) Media Freedom Report also ranking the Philippines as the worst offender for media impunity in Southeast Asia because of its high number of media killings.

13 journalists have been killed since Rodrigo Duterte took office in 2016. Speaking to Filipino media last month, University of Philippines journalism professor Danilo Arao stressed that the country’s culture of impunity is putting journalists at risk.

“We foresee that journalists will really be put in peril. If they are not caught in the middle, they themselves can be victims of harassment and intimidation,” he said.

The Maguindanao massacre, when 32 journalists and media practitioners were among those killed in a deadly ambush of 58 individuals on their way to a 2009 electoral event in a town on the island of Mindanao, remains the single deadliest event for journalists in history. While over 100 suspects are on trial, no verdict has been announced to this day despite the fact that the victims were gunned down nearly 10 years ago.

Proper training

Probably no one understands the anguish of such killings more than Diane Foley, whose son, James Wright Foley, was kidnapped by the Islamic State (IS) while working as a freelance correspondent in Syria in 2012. Tortured and beheaded in 2014, James’ murder was the first of an American citizen by the IS.

While Diane recently pointed out that bringing those responsible for abducting, imprisoning, torturing and murdering journalists to justice is critical to create an effective deterrent, merely working to increase accountability is not enough – and steps must be taken to increase the safety of journalists.

The James W. Foley Legacy Foundation has helped develop a safety guide to educate journalism students on how to protect themselves, and these modules – such as risk-assessment and digital-security skills – identify the potential dangers of reporting not only in conflict zones but also in non-threatening environments.

“That way, when they start their careers, they will already be in the habit of taking the necessary precautions,” said Diane. “All journalism schools should add such modules to their curricula, thereby ensuring that their graduates are as skilled at staying safe as they are at reporting the news,” she added.

The United Nations (UN) has also drawn attention to the dangers of journalism, noting the rise in the scale and number of attacks against journalists and media workers – which included threats of prosecution, arrest, imprisonment, denial of journalistic access and failures to investigate and prosecute crimes against them.

“When journalists are targeted, societies as a whole pay a price,” said UN Secretary-General António Guterres on Thursday.

“Without the ability to protect journalists, our ability to remain informed and contribute to decision-making is severely hampered.

“Without journalists able to do their jobs in safety, we face the prospect of a world of confusion and disinformation.”

Related articles:

Philippines, the most dangerous country in Southeast Asia for journalists