As Myanmar celebrates its 99th National Day today, the challenge of how best to balance its rich architectural and cultural heritage with the demands of modern development is as important as ever.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in the port city of Yangon, the country’s former capital which has the distinction of having the densest concentration of colonial-era buildings of any city in Asia.

The biggest city in Myanmar, Yangon’s 19th- and early 20th-century colonial architecture was slowly replaced by dozens of new apartments, offices and hotels after the country opened its economy in 2011.

Around 1,800 old buildings – or 35 percent of downtown Yangon – were demolished between 1990 and 2011 to make way for new projects according to non-governmental organisation (NGO), Yangon Heritage Trust (YHT), that carried out a 2017 survey which found there were 6,000 heritage buildings in Yangon.

Issues at key buildings

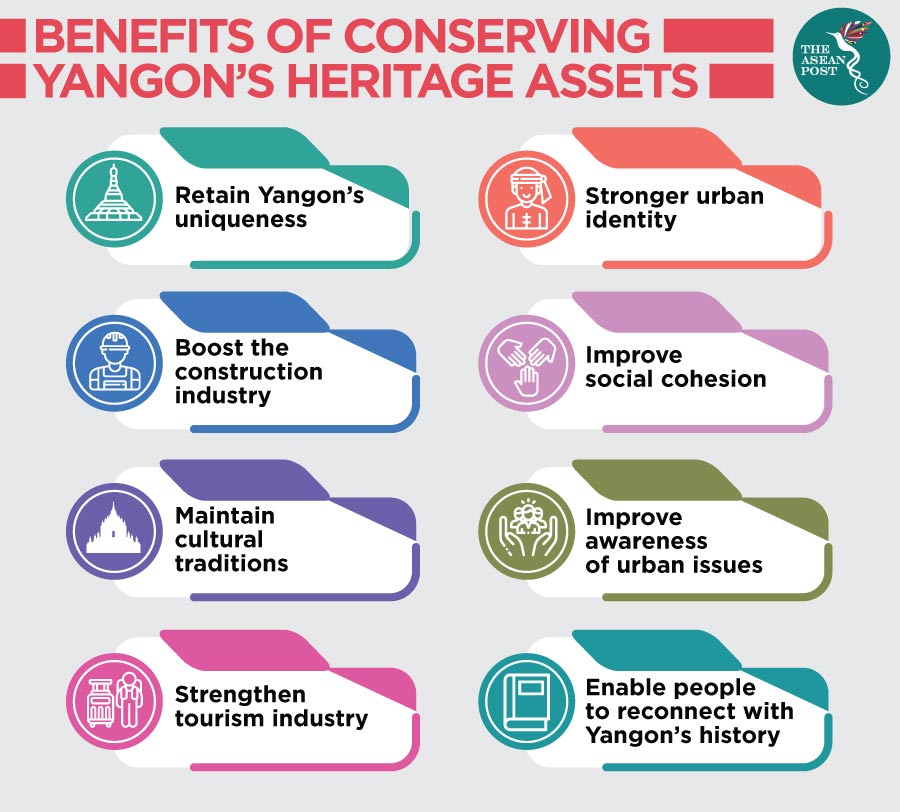

Yangon’s city planners and related stakeholders are growing increasingly aware of the benefits of preserving its heritage buildings, and the Yangon City Development Committee, the city’s municipal authority, created the Yangon City Heritage List in a bid to preserve the city’s heritage sites.

However, there is nothing preventing the buildings on the list from being demolished or used for other purposes.

Last year a prominent businessman tore down the Mayor’s Residence – a British colonial-era building once home to Yangon’s mayors – despite it being on the list. However, his plans for a US$500 million high-rise project were soon halted when he was ordered to rebuild the building in its original form.

Earlier this month, a Singaporean company was forced to shut down a spa that it opened in the historic Secretariat building after criticism that it was insensitive. The former headquarters of the British administration, the courtyard’s flagstaff hoisted the flag of a newly independent Burma for the first time on 4 January, 1948 – and the building was also where independence hero General Aung San, the father of Aung San Suu Kyi, was assassinated along with other colleagues in 1947.

Renovation in the private sphere

There are some bright spots in the private sphere though, where social enterprises such as Doh Eain are playing a pivotal role in restoring privately owned heritage buildings and improving public spaces in Yangon.

Founded in 2017, the firm works with building owners and neighbourhood residents to renovate historical buildings in the city and increase their value. Among the 20 houses Doh Eain has renovated include the former home of author George Orwell, who lived in then-Burma in the 1920s.

Some of their other projects include creating playgrounds and exercise areas for girls and young women, and repurposing back alleys formerly used as rubbish dumps into recreational spaces featuring gardens and street art.

“Sometimes people are too focused on the new,” Doh Eain’s founder and director, Emilie Roell, told The ASEAN Post.

“Land prices have gone up since 2011 and mixed-use developments are growing in Yangon. In the last six years alone there have been eight big malls built,” said Roell, who was in Malaysia recently for the Placemaker Week ASEAN conference.

Urban development

As Yangon Heritage Trust director Moe Moe Lwin observed in an interview with research firm Oxford Business Group last year, the pressure resulting from urban development is arguably the central challenge to the city’s heritage.

Warning that if construction and investment in Yangon is not implemented with a holistic vision for the future, growing demand for new residential and commercial properties will “cause many buildings to disappear like they have in other cities across Asia.”

Apart from a moratorium on demolition of heritage assets, the Yangon Heritage Trust has also called for an increased awareness of conservation and planning benefits and guidelines for new development in conservation areas.

With several key real estate developments in the pipeline, it is vital that modern high-rises in Yangon are limited to certain areas while the historic core is preserved for future generations.

Ultimately, for both public and privately owned heritage buildings in Yangon, the lack of a formal comprehensive legal framework for their management remains the biggest concern moving forward.

Related articles: