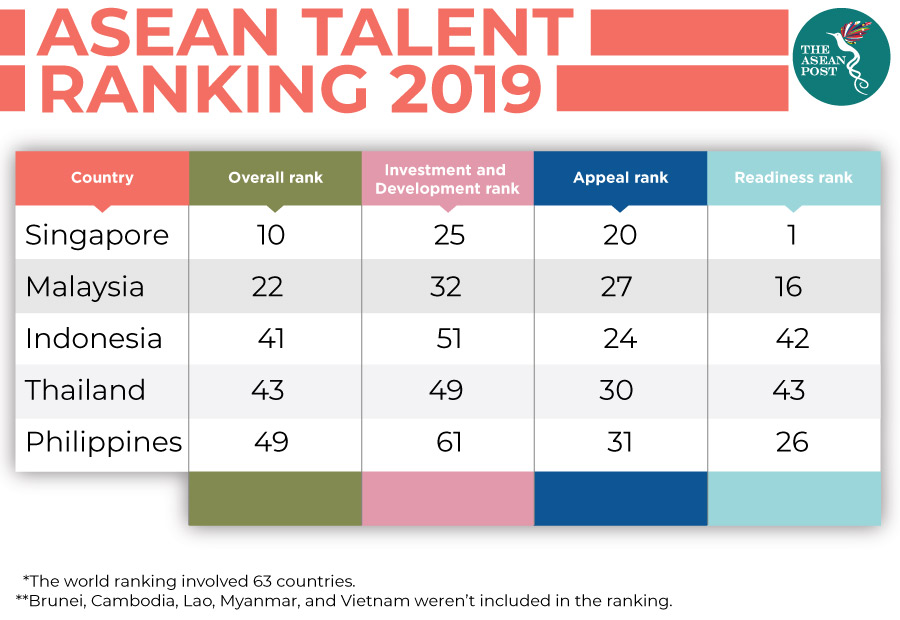

The research arm of Switzerland-based business school, the International Institute for Management Development (IMD) recently released the results of its survey on the talent competitiveness of 63 countries from around the world. Based on the rankings, the Philippines managed to jump up to 49th place from 55th last year.

Regardless of the jump, the ASEAN country, unfortunately, still performed the worst when compared to other bloc members. In order to understand how this happened, it’s important to look at what the study uses for its indicators.

The World Talent Ranking looks at three main factors when determining how to rank a country. The investment and development factor, which measures resources used to cultivate homegrown human capital; the appeal factor, which evaluates the extent to which a country attracts and retains foreign and local talent; and the readiness factor, which looks at the quality of skills and competencies of a country’s labour force.

While a simple example of the investment and development factor would be whether a country is able to provide education to its citizens, the readiness factor seems to indicate that it is also important to look at the quality of the education provided. This, according to the study, is where countries like the Philippines fall short.

Quality of education

For the three factors, the Philippines scored 31st for appeal, 61st for investment and development, and 26th for readiness. Similarly, last year, the Philippines scored lowest for investment and development.

In 2018, the IMD World Competitiveness Center’s director, Arturo Bris told the media that the Philippines’ labour force is not as equipped with skills that firms are looking for.

He acknowledged that it was true that the Philippines was making progress in managing its talent pool and is, in fact, one of only two countries in Southeast Asia along with Malaysia which has improved government investment in education as a percent of gross domestic product (GDP).

“However, in 2018, The Philippines witnessed a deterioration of its ability to provide the economy with the skills needed, which points to a mismatch between school curriculums and the demands of companies,” he said.

But it isn’t just a Swiss business school that thinks the Philippines needs to improve its quality of education. In June last year, local media reported the Philippine Business for Education (PBEd) as saying that while the state of education nationwide has progressed in terms of accessibility, it still has a long way to go when it comes to delivery of quality learning for the success of every learner.

PBEd executive director, Love Basillote said this can be attributed to many factors such as prevalence of malnutrition and a shortage of appropriate learning tools, adding that many college graduates are not work-ready due to a lack of socio-emotional skills.

“Our recommendation is we focus on learning by starting early, monitoring learning, raising accountability and aligning actors,” she said, also suggesting that the country participate consistently in international learning assessments to make Filipino learners and graduates globally competitive.

The World Talent Ranking 2018 cited the country’s top weaknesses in the areas of total public expenditure on education, pupil-teacher ratio in primary and secondary schools, and remuneration in service professions and labour force growth.

Upgrading digital skills

The World Economic Forum (WEF) head of Asia Pacific and Member of the Executive Committee, Justin Wood noted that Industry 4.0, also known as the Fourth Industrial Revolution, was unfolding at accelerating speed and changing the skills that workers will need for the jobs of the future.

On 19 November last year, a coalition of major technology companies pledged to develop digital skills for the ASEAN workforce. Being part of the WEF’s Digital ASEAN initiative, the pledge aims to train some 20 million people in Southeast Asia by 2020, especially those working in small and medium-size enterprises (SMEs).

The move is most welcomed especially due to the threat of huge job displacement across the region. Now, following results from the World Talent Ranking, it seems that this initiative would be much needed in the Philippines as well.

However, the Philippines must understand that the pledge will only go so far in ensuring that it has the right workforce for the new skills demands of companies. Improving the quality of education in the country is still critical and as 2019’s results highlight, the Philippines needs to continue working on this.

This article was first published on 5 December, 2019.

Related articles: