We see them in the business district and in the suburbs; on the streets, in our apartment blocks and offices. The food delivery riders with brightly coloured backpacks advertising the logos of their operators, Gojek, Grab, Foodpanda and Deliveroo amongst others, on their missions to deliver lunch or dinner to ASEAN’s hungry workforce.

This would not come as a surprise particularly to consumers of the millennial generation. 43 percent of respondents aged 25 to 34 in a recent GlobalData study indicated that they had recently ordered takeaway food.

Although delivery riders have become an increasingly visible part of the community, few of their customers ever really give much thought to their growing numbers and their role in the changing way that food is consumed. And perhaps how important delivery riders have become to our society.

The invention of the battery driven personal mobility device (PMD) has provided a boost to the delivery system and created jobs opportunities that do not require a particular skill or license. This is a rare accomplishment in a global economy that is rapidly dispensing with low skilled jobs.

On the economic front, the advent of home delivery has also provided a new stream of revenue for the restaurant sector. The trend of “cocooning” (spending leisure time at home rather than going out), seems to be growing in popularity in the region particularly in Singapore. In the GlobalData report “The Future of Foodservice”, the rise of cocooning has been partly attributed to the ability to order high quality restaurant meals without leaving the home or office.

ASEAN cities have a perfect combination of factors for this trend to take off: an increasingly affluent and time-poor population that enjoys a good meal; a plethora of cuisines from high-end to fast food, connected to most homes and offices through a diverse transport infrastructure that might include trains, buses and taxis as well as rickshaw and motorbike services; and a workforce of delivery people.

Restaurant owners stand to gain from this trend. Food establishments can theoretically now sell beyond the capacity of their seats. Take away orders require less waiting and washing up time. However, this does come with the lost opportunity for upselling additional items, receiving tips, selling additional higher margin alcoholic drinks and receiving social media publicity.

Home delivery is also creating business opportunities for chefs with no restaurants, operating from home or from a shared kitchen in a lower cost part of town. This means no investments are needed for pricey real estate and expensive designs and décor.

Home delivery does, however, come with an environmental cost. The additional transportation as well as the packaging required to deliver a cooked meal to a home adds more to the overall carbon footprint.

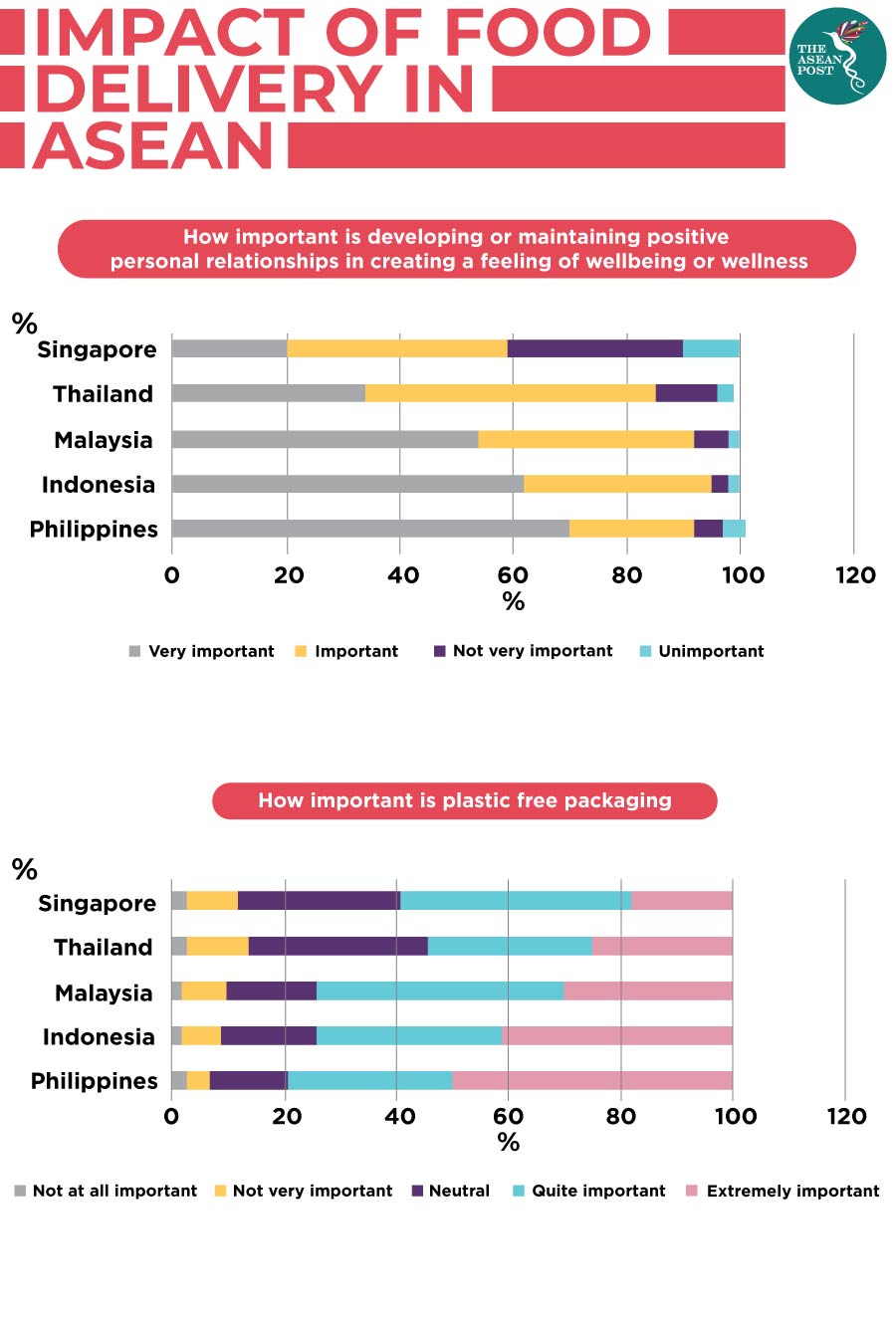

The implications for this do not seem to resonate particularly with all consumers in the region. When asked in the GlobalData Asia Pacific Consumer Survey how important is it for packaging to be plastic-free, only 33 percent of ASEAN respondents indicated that it was “extremely important” with the lowest being Singapore (18 percent) and the highest being the Philippines (50 percent). Any visitor to the central business districts of the capital cities during lunch times would be able to vouch for this by the sheer numbers of office workers dangling take-away drinks with straws and plastic carrier handles.

There may also be a social cost. As well as the missed health benefits of a walk to a street vendor, there are other implications for wellbeing with the cocooning trend. The easier it is for society to avoid interactions, the more insular we will become and the less opportunities we will enjoy for new experiences. Eating out offers the serendipity of stumbling across a new food outlet, or trying a new cuisine. Social opportunities abound with the possibility of running into an old friend or making a new one.

Again, this does not seem to resonate as strongly across all ASEAN consumers. When asked in the same survey ‘How important do you consider developing or maintaining positive personal relationships in creating a feeling of wellbeing or wellness’, 48 percent of regional respondents decided this was ‘very important’. At the upper end of the scale, 70 percent of respondents from the Philippines and 62 percent of respondents from Indonesia decided that personal relationships were ‘very important’.

The two countries that gave lower scores to the importance of personal relationships were Singapore (20 percent) and Thailand (34 percent) – where the trend of take away and delivery food are the highest.

Taxi operators such as Grab and Gojek have recognised this growing ASEAN-wide market for home delivery. As well as offering traditional taxi rides, they also bring food deliveries, masseurs and home repairmen.

It is perhaps not too far-fetched to imagine a scenario in the future where the only significant human interaction some people have is with their deliveryman. The irony is that the cocooners may wish to isolate themselves from society but will still need to live in urban areas, because that is where the delivery systems are fastest, cheapest and most efficient.

Related articles:

Food delivery services in Southeast Asia

2018: A transformational year for ride hailing