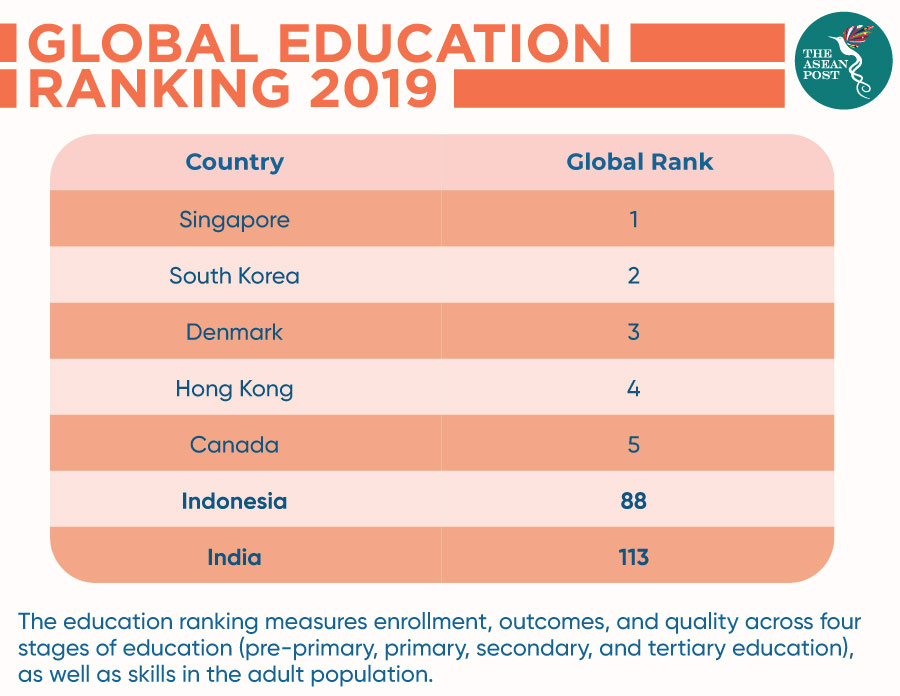

In the endeavour to build the future of any nation, higher education contributes significantly by providing “global competitive talent”. The skilled workforce coupled with innovative technology and advanced infrastructures are key drivers for any country’s sustainable growth. In that context, if we inspect both India and Indonesia – two of the most populous economies – it’s evident that they are facing some of the biggest global challenges: the rapid ascension of artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning (ML), automated learning (AL) and the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Both nations are struggling to equip their respective workforces with advanced skills, attitude and knowledge essential to stay relevant in today’s education 4.0 era.

These two countries share similar peculiarities – a vibrant and energetic youth – and are faced with the same question: “How to equip their higher education system for challenges associated with ever-evolving global technological advancements, and transform their institutions into 'world class’ universities?”

Nevertheless, the scenario for India is marginally better as the sub-continent has supplied “some” of the world’s best talents in the past. For instance, CEOs at a few global companies like Adobe, PepsiCo, Google, and Microsoft are all Indians, and the landscape has expanded over the last decade. A recent Deloitte report has shown that the number of universities in India has slowly grown from 436 in 2009–2010 to 903 in 2017–2018. The number of colleges rose from 29,000 to 39,000 in 2010. In addition, with record-breaking student enrolments (35.7 million students) India stands as the third-largest in the world, next to China and the United States (US), but despite that, the country still lags behind the standards of the world’s best universities.

While for Indonesia the agony is more severe as, in the past, it has supplied high volume but low-quality human capital. Surprisingly, according to research conducted by the Global Business Guide (GBG), Indonesia has 4,498 universities providing 25,548 majors, which is nearly double that of China, (2,825 universities); with a population that is less than one fifth of the latter. The country, in reality, is facing a 50 percent shortage of skilled workers according to data from the World Bank.

Quality versus quantity

Merely having a massive number of universities and a record-breaking number of student enrolments does not guarantee quality. Rather, a robust and updated academic curriculum decked up with technological advancements, industry-academia collaboration, enough research funding, and quality global research, is required to transform a country’s education institutions into world class universities.

Since, in these economies, most of the universities or institutions are, mostly, privately owned, the quality of education imparted is mostly substandard resulting in “ill-equipped” graduates which encumber the global competitiveness of these countries. Merely three national universities in Indonesia managed to penetrate the world’s top 500 universities listing while India has 16. Though the latter ranked higher than Indonesia, globally, both are still far behind China and Japan with 39 universities, or South Korea and Taiwan with 24 universities.

Fearing this alarming situation, the education ministries of both nations have issued several decrees. The Ministry of Research, Technology and Higher Education in Indonesia has allowed for the appointment of foreign permanent lecturers in their public and state-owned universities and are inviting foreign universities to collaborate with local universities to boost academic achievements.

According to Universitas Sangga Buana YPKP in Kota Bandung in West Java, the Indonesian government has given its permission for 200 foreign lecturer appointments to speed up the growth of the country. On the same note, India’s former Minister of Finance and Corporate Affairs, the late Arun Jaitley made the Higher Education Financing Agency (HEFA), a non-profit organisation accountable for ameliorating the infrastructure of the country’s premier universities and establishing “20 world-class universities”.

Research

Research quality and quantity issues have been an ongoing debate for ages around the globe. The plethora of research literature available globally in the realms of science and business is imposing tremendous pressure on the peer review system. Every year, around two million scientific papers, as per an estimate, are published by 30,000 journals globally, mostly from countries like the United States (US), United Kingdom (UK), Germany, and China.

On a positive note, according to the SCImago journal and country ranking, research publications are gradually increasing for both, India and Indonesia with approximately 1,670,099 papers for India and 110,610 for Indonesia. While India is clearly ahead with a global ranking of nine, it still has far to go to move up in the academic world. Both countries should invest in bolstering the number of quality research publications and develop skilled, productive and flexible labour forces such as those found in the US, UK, China, and South Korea.

Faculty

Another critical determinant for a world-class university is having acclaimed and meritorious faculty pools who are excellent in the classroom. However, sadly, both countries lack in this regard too.

According to a report by global technology specialists, GBG, most lecturers (approximately 155,591) working in Indonesia only hold a Master’s level degree. In a few cases (34,393) even Bachelor’s degree holders are permitted to teach.

According to the National Education Policy Draft Report, the quality and standard of education imparted in India is largely below the mark. The faculties are underpaid and the majority work on an ad hoc basis which eventually forces them to seek other career options which offer more appealing salary packages coupled with higher career growth prospects. In fact, it is speculated that India will soon experience around 30 to 40 percent paucity of eligible lecturers.

Funding

Sufficient funding is another key ingredient for producing independent, high-quality research and in that respect, during the last couple of years, the Indian government has remained stagnant and even moved backwards as a funder for both, public and private universities. In Indonesia, funding is gradually increasing. In 2017-2018, Indonesia’s research expenditure was 0.24 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP) whereas India’s expenditure on research stood at 0.62 percent versus China’s 2.06 percent, Singapore’s 2.36 percent and Malaysia’s 0.63 percent. Public funding, somehow, for education has remained inadequate for both countries compared to other developing nations such as Brazil and South Africa.

Higher education in both nations desperately need a revolutionary change where “industry oriented and focused teaching” is desirable. Though India stands ahead when compared to Indonesia, it is still far behind in the global ranking. The governments of both emerging economies should initiate and design innovative solutions to stand against the global forces of change. Perhaps developing an “eco-system” among all the constituents of higher education – educational institutions, students, alumni, regulatory bodies and accreditation agencies, employers, and governments – can speed up their growth and aid them in remaining relevant in the era of Education 4.0.

Related articles: