As of February, Indonesia is home to more than 272 million people, making it the fourth largest population in the world behind China, India and the United States (US). The nation is expected to hit 300 million people by 2050. The populous country contributes to a domestic workforce surplus. And when combined with a scarcity of jobs, leads to a growing number of Indonesians seeking work overseas in a way to earn money and improve their economy.

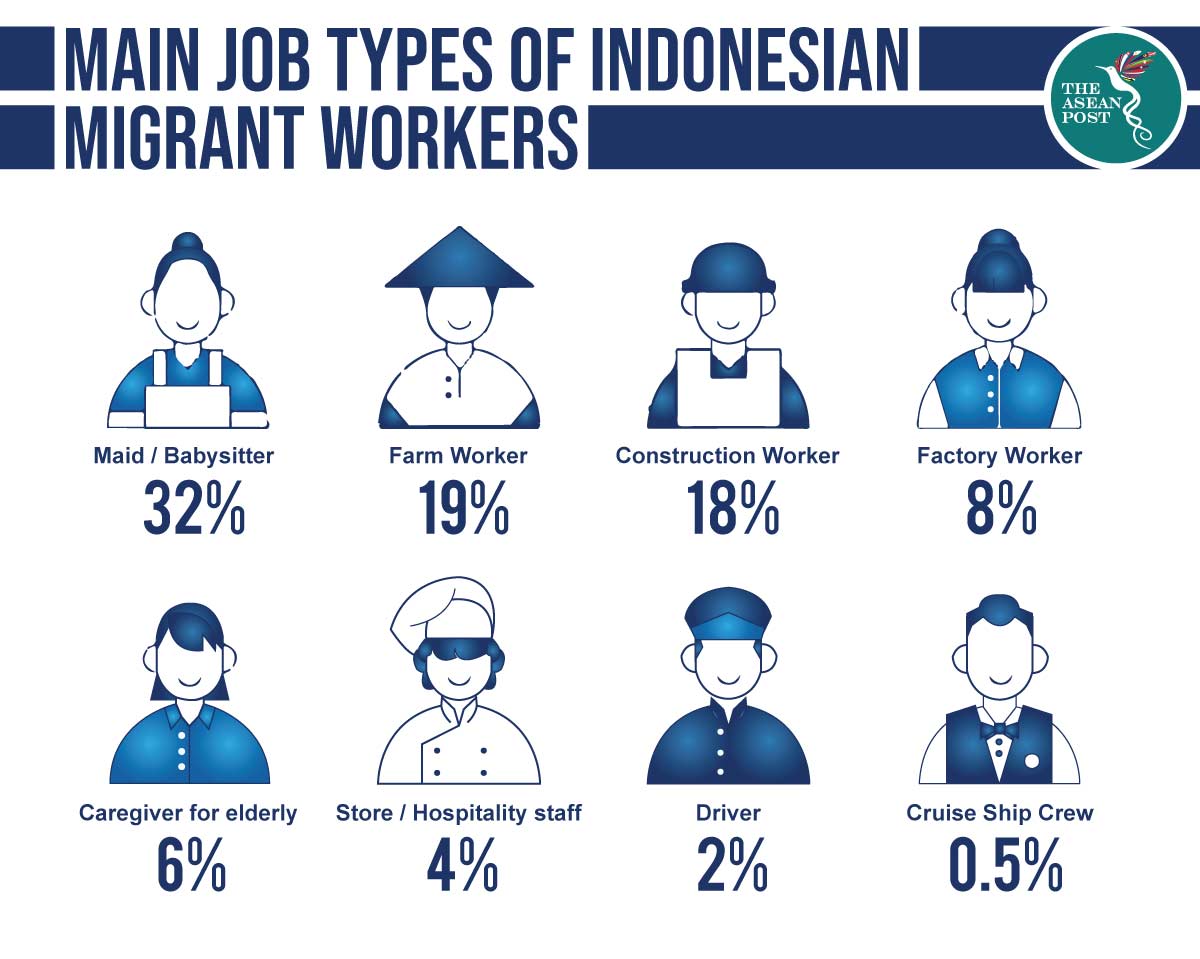

Indonesia has one of largest migrant workforces across the globe. It is difficult to put an actual figure of Indonesian migrant workers as some of them enter illegally or are even trafficked into other countries without official documentation. However, in 2018, rights group Migrant CARE estimated that about 4.5 million Indonesian domestic workers were abroad. According to reports, domestic workers make a huge contribution to Indonesia’s economy through the billions of dollars in remittances and wages that enter the Indonesian market each year.

As noted by the International Labour Organisation (ILO), the domestic work industry remains a feminised sector with 80 percent of all domestic workers comprising women and girls. Indonesian domestic workers are incredibly in demand in countries like Malaysia, Singapore, Hong Kong and the Middle East - yet they are undervalued and typically exposed to multiple vulnerabilities. In recent years, it is common to read headlines and hear stories of “maids” – as they are called sometimes, being abused by their employers.

In 2018, an Indonesian domestic helper, Adelina Jerima Sau died in Malaysia after she was believed to have been abused by her employer. A picture of the helper, taken by a neighbour – captured the Indonesian in a weak state and stranded outside her employer's house, which was circulated in the media and caused an uproar among members of the public. Her employer escaped the death sentence after the High Court freed her from a charge of murdering the worker. This led to a petition signed by 15,000 people demanding Malaysia’s courts explain the reasons for dropping the murder charge against Adelina. There have been no known updates on the case till today.

In Singapore, just last year, a couple was sentenced to jail after they were found guilty of abusing their Indonesian helper. The incident was dubbed as one of the worst cases of migrant worker abuse in recent years. The abusers knocked her teeth out with a hammer, stabbed her in the shoulder with a pair of scissors and hit her with a bamboo pole which left the helper’s left ear lobe completely deformed. She also had signs of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) following the series of abuses.

Another shocking case was the beheading of Tuti Tursilawati in Saudi Arabia. The Indonesian victim claimed that she was defending herself from being raped by her employer when she killed him in 2010 and that it was an act of self-defence. Nevertheless, Saudi Arabia proceeded with her execution without informing the victim’s family and the Indonesian government. This was not the first execution of an Indonesian migrant worker in the country.

Migrant workers are generally poor and uneducated – leaving their home country in hope of gaining experience, skills and money to be sent back home. It was reported that Indonesian domestic workers typically make HK$500 (US$64) a month in Hong Kong, compared to the average income of US$10 if they were to work in Indonesia.

Enhancing skills at training centres is the first step in the long process of becoming an Indonesian domestic worker. Some centres even provide language classes such as English and Cantonese for those who want to work in Singapore and Hong Kong. Practical skills such as taking care of the elderly, feeding a baby and operating a vacuum cleaner and washing machine are all taught in meticulous detail. These skills add up to a higher salary compared to what they can make at home. Training centres for domestic workers are available in Indonesia.

Maid agencies

Many maid agencies have their own international partners who supply workers to various countries. In Malaysia, employers can find a domestic helper directly through personal contacts or through agencies that help with the paperwork; obtaining work visas and sometimes training the helpers themselves.

Unfortunately, some domestic workers experience abuse at the very beginning of their journey as a migrant worker – even before they are assigned to their future employers.

According to media reports, a number of Indonesian migrant workers have been cheated and lied to by agencies. They are often promised jobs in domestic work but end up working in restaurants or massage parlours without receiving any payment or wages. In other cases, they are promised other forms of employment but end up as domestic workers, again without payment. Some were even abused verbally or physically during training sessions at the agency – in order to supply “high quality maids” to clients.

There have also been reports of agencies forging workers’ dates of birth to make them older than their true age, which has fuelled the ongoing problem of child labour. Some argue that this can be considered as child trafficking. Underage migrant workers are often school dropouts and don’t understand the implications of working hard labour jobs abroad. They are made to sign forms that they don’t even understand. And when underage domestic workers suffer some sort of abuse by their employers, they are too afraid to lodge a report for fear of getting into trouble with the law.

Cynthia Abdon-Tellez, general manager of the Mission For Migrant Workers in Hong Kong said that “there are hundreds of Indonesian domestic helpers who are underage... and a few Filipinos [we know of]. It is child trafficking. It is evil. It damages the child.”

Indonesian domestic workers encounter a wide range of human rights abuses including extremely long hours of work without overtime pay, no rest days, psychological, physical, and sexual abuse, poor living conditions, restrictions on their freedom of movement and in some cases, being trafficked into situations of forced labour. Despite the number of organisations voicing out for better welfare of migrant workers, and authorities introducing policies for better care of foreign workers –cases of abuse and trafficking of migrant workers are still rampant across Southeast Asia.

Related articles: