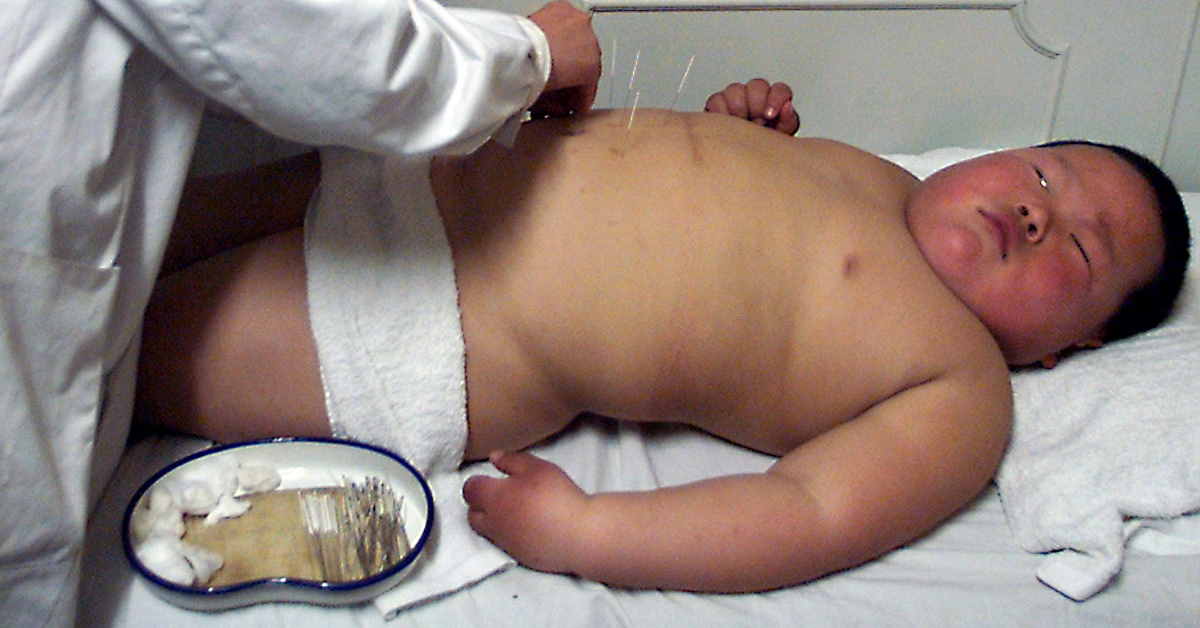

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), the prevalence of childhood obesity has increased at an alarming rate globally. In 2016, the number of overweight children under the age of five was estimated to be over 41 million.

Southeast Asia has seen an upward trend in childhood obesity during the last 10 to 15 years. An estimated 6.6 million children under five years are currently overweight in the region. Moreover, the growing paradox of under-nutrition and obesity in the same population, commonly described as the double burden of malnutrition, impacts the health status of the population and is straining national health capacities.

The Asian Development Bank Institute (ADBI) has estimated that the cost to the Asia-Pacific region for overweight or obese citizens is US$166 billion a year. The rapid rise of obesity in the region is incredibly worrying because overweight children are at higher risk of becoming obese adults and then developing serious health problems such as type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure and liver disease.

Asian Development Bank (ADB) economist, Matthias Helble said that rising wealth over the last 20 years have played a major role in the rise in obesity levels, adding that an affluent new lifestyle has caused a rise in the consumption of convenience and processed foods, which often contain excess fats and more salt and sugar.

Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines and Vietnam are all considered to have “public health concerns” caused by both, undernutrition and excess weight, according to the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF). In Indonesia, 12 percent of children under five years of age – 2.89 million – are overweight.

In countries such as Cambodia, excess weight issues and obesity have not yet become prominent, with only 3.9 percent of the adult population considered obese in 2016.

Is ASEAN doing enough?

To combat the findings released by the WHO on the rate of obesity in Southeast Asia, most ASEAN countries – Thailand, Cambodia, Philippines, Brunei, Lao PDR and more recently, Malaysia – have opted for an easier solution, which is to impose a sugar tax or commonly known as soda tax.

Although Singapore does not have a sugar tax yet, it has launched a war against diabetes. In August 2017, its health ministry announced that seven key beverage manufacturers had committed to limiting the sugar content in their drinks sold in Singapore to a maximum of 12 percent by 2020.

Singapore has adopted different strategies that incorporate a growing number of studies that have debunked the effectiveness of a sugar tax. For instance, research from Duke University and the National University of Singapore released in December 2010 tested larger taxes and determined that 20 percent and 40 percent taxes on sugar-sweetened beverages would largely not affect calorie intake because people would switch to untaxed, but equally caloric, beverages.

However, to develop and implement a comprehensive action plan against childhood obesity is costly and requires an overhaul to the daily routines of children in school and at home. Governments would need to make a significant commitment to embed at least some of the effective and feasible policy actions aimed at increasing physical activity and promoting healthy eating among children.

An example would be a campaign started in England 10 years ago to provide free healthy meals for all children aged between four and seven. This has resulted in a seven percent drop in obesity among four-and-five-year-olds, the World Economic Forum (WEF) reported. While countries like Finland and Sweden have successfully implemented the same program for primary school students, Malaysia sparked a heavy debate when its previous Education Minister, Dr Mazlee Malik implemented a free breakfast programme to promote healthy eating among school pupils, mostly in regards to wasting taxpayer money.

Although costly, ASEAN countries would need to take a stronger stand in their policies to tackle childhood obesity as well as its prevalence among adults. Considering that Southeast Asia now accounts for about 20 percent of all diabetics globally, it is indeed a major concern that would require heavy spending for a long-term solution.

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development includes obesity as a non-communicable disease (NCD), and a concerning factor to sustainable development. As part of the Agenda, heads of state and governments are committed to developing ambitious national responses, by 2030. This is to reduce by one-third premature mortality from NCDs through prevention and treatment.

The "Global action plan on physical activity 2018–2030: more active people for a healthier world" provides effective and feasible policy actions to increase physical activity globally. The WHO has published ACTIVE, a technical package to assist countries in planning and delivering their responses effectively.

Related articles: