Strict measures are being taken by countries around the world to contain the deadly COVID-19 virus. As of 25 March, over 400,000 people have been infected with more than 20,000 deaths recorded worldwide. Officials in China have told the media that the country’s central Hubei province, where the novel coronavirus first emerged late last year, is to lift curbs after two months under lockdown. Other nations have been following China’s drastic but successful strategy of city lockdowns and travel curbs to break the chain of infection.

Thailand became the latest country in Southeast Asia to impose a partial lockdown. On the night of 25 March, the kingdom’s borders were reported to be closed to all foreign visitors. Gatherings have been outlawed and domestic travel is now restricted for all Thais. The state of emergency will continue until 30 April, although some essential shops will be allowed to remain open. Just a few days earlier, the country saw thousands of its migrant workers flee the country as malls and businesses were shut during the weekend over virus fears. Migrants from Lao PDR, Myanmar and Cambodia make up the bulk of the estimated four million workers in the kingdom.

“Thailand is at a turning point in the outbreak and the situation could get a lot worse,” said Thai premier Prayut Chan-o-cha, “It’s important that we impose stricter rules to reduce the spread”.

Other ASEAN countries that have implemented such tough action include Malaysia and Lao PDR. Malaysia began its initial two-week Movement Control Order (MCO) on 18 March. However, as the number of cases continued to rise (1,796 positive cases as of 25 March) – the highest in the region – Malaysia’s authorities decided to extend the MCO until 14 April. Lao PDR, which reported its first two COVID-19 cases on 24 March, has prohibited its people from traveling abroad for tourism purposes amid the pandemic. It was reported by local media that only individuals traveling on government duties or for medical purposes are allowed to leave the country.

The struggle

In mid-March, Philippine’s president Rodrigo Duterte declared a lockdown of the country’s capital, Manila – home to 12 million people – in order to curb the spread of the COVID-19 virus. A few days later, an “enhanced community quarantine” was imposed on the whole of Luzon island, where half the population of the Philippines live. Mass gatherings were prohibited, schools shut down and all public transportation has been suspended. However, the operations of essential services such as hospitals, pharmacies and hypermarkets – are allowed to continue. The lockdown – although some argue to be necessary in combating the virus – has taken a toll on livelihoods, especially those of the poor. According to the Philippines Statistic Authority, the poverty incidence among the people of the Philippines in the first half of 2018 was estimated to be 21 percent.

As many nations are encouraging and practicing social distancing, for most of those living in extreme poverty, this is an additional burden. For the Philippines, where it was reported that one in five people in the country live below the poverty line, impoverished communities in the densely populated city of Manila struggle to adhere to the practice. The chairperson of Kadamay San Roque, a group that fights for the rights of the urban poor in San Roque, a community in the Quezon City area of Metro Manila, Estrelieta Bagasbas, said that this is because “the homes are small, they cannot afford to do the distancing”. Isolation and sanitation are considered privileges that the people of Manila’s slums simply can’t afford. One of its dwellers, Mary Grace Aves told the media that “it may be possible (to isolate) in other areas because they are rich. They have big spaces,” adding that “here, we are crammed.”

A virus infection would be easily spread in narrow passages between homes – a space just enough for one person to pass through. Therefore, locals touch frequently as they slide past one another to move about. According to media reports, in some slums, daily necessities such as cooking and personal hygiene are done in common spaces filled with people. This indicates that locals would have to be in public in order to survive.

Apart from the impacts of the virus on local industries, the fate of those who earn a daily wage instead of a stable, monthly pay-check has also raised concerns among the general public regarding their wellbeing during the lockdown. It was also reported that many people have been retrenched from work or have been asked to take unpaid leave for the time being.

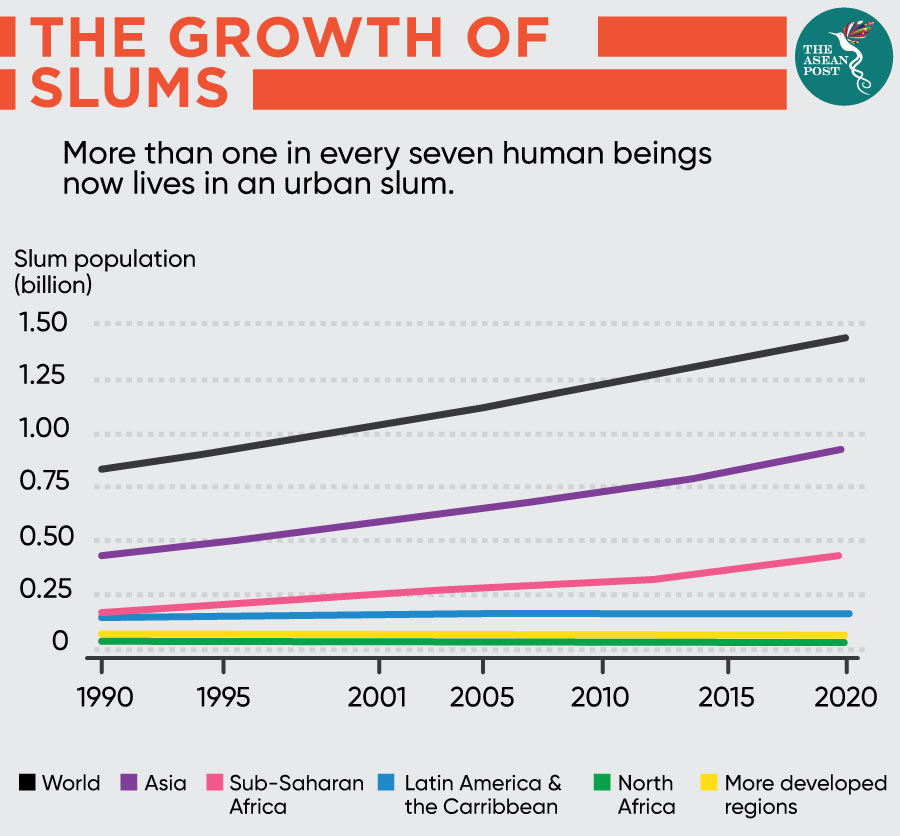

According to the United Nations (UN), it is estimated that in 2007, one billion people were living in slums, and that number could reach 1.39 billion in 2020. Based on a report by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) titled, ‘The Urban Revolution’, Asia has the highest number of city dwellers living in slums, particularly in South Asia. Just recently, India announced its own lockdown after an increase in the number of COVID-19 cases on the sub-continent. Media reports suggest that developing countries with densely populated cities and slums could see the coronavirus spread like wildfire.

A number of efforts have been initiated by governments across the globe to help those who are struggling amid virus lockdowns. Authorities and banks have introduced temporary deferment of loan repayments, cash assistance, stimulus packages, and electricity bill discounts among others. However, many argue that these solutions are not enough – sometimes not even applicable – to those who live in extreme poverty.

Underdeveloped countries such as Myanmar and Timor-Leste would be hit hardest by the virus and its impacts. Mthandazo Ndlovu from Oxfam, a charitable organisation, urged countries that are on lockdown to ensure that the poor are not left behind to defend themselves alone.

Related articles: