The Philippines reported 538 new cases in the past 24 hours, bringing the total number of cases in the country to 2,084 as of 31 March 2020 – the highest overnight jump recorded in ASEAN. The country also has a fairly low rate of recovery (49) compared to Malaysia (537) and Thailand (342).

In the second week of March, the Philippines government called for a lockdown of Metro Manila followed by an enhanced lockdown of Luzon island – which is home to about 60 million and is responsible for 70 percent of the Philippines' economic output.

The lockdown has since been extended to the entire country, and it has been nothing short of a chaotic experience for most residents. Duterte’s administration has been criticised for not issuing a comprehensive guideline for citizens to adhere to following the lockdown. This has been exacerbated by police checkpoints that have caused massive traffic jams for pedestrians, motorists and vehicles – making it almost impossible to maintain proper social distancing.

The traffic gridlock can be attributed to a misunderstanding of orders as well as workers who simply cannot afford not to go to work. In La Trinidad, the capital of the province of Benguet, precautions against the spread of COVID-19 have made it tough for farmers to deliver vegetables as they have to stop at several checkpoints before queuing at two trading posts to wait for buyers. More time on the road leads to poor quality of leafy vegetables, thus reducing their value.

The Mayor of La Trinidad, Romeo Salda on Saturday said trucks and cargo would not be allowed to transport vegetables on Monday and Tuesday because local government and health workers were tracing people who may have interacted with two people infected with the coronavirus.

The Philippines faces another challenge – food shortage. Residents in various parts of Luzon have complained that the financial assistance promised by the government on 16 March has yet to reach them.

Local media reported that some residents have started eating corn fungus and resorted to planting their own vegetables.

It is estimated that around 18 million low-income families have not received the P5,000 (US$98) to P8,000 (US$157) two-month cash subsidies under the "Bayanohan to Heal as One" law.

Even without the threat of a pandemic, the Philippines faces multiple challenges with regards to food security. In 2019, the World Bank reported that at least 20.8 percent of Filipinos are living below the poverty line while data from the Food and Nutrition Research Institute (FNRI) currently reports chronic malnutrition among Filipino children aged zero to two years at 26.2 percent, the highest in 10 years.

Things will not get easier for the Philippines as Vietnam on Friday announced that it plans to stockpile its rice and suspend new rice export contracts to ensure that it can feed its population of 97 million throughout the COVID-19 crisis.

This means that big rice buyers such as the Philippines – the world’s top rice importer in 2019 – and other countries in Asia and Africa could be vulnerable if population movements are curtailed for an extended period of time.

Local rice farmers in the Philippines are encouraged to sell their harvest to village officials so rice distribution would remain unhampered in their respective communities.

“Our rice inventory is good for 65 days. We have enough rice for the next two months,” said William Dar, Philippines Agriculture Secretary, adding that with additional supply coming from the dry season harvest, there would be enough rice for the country for the next four months.

Gideon Lasco, an academic and columnist said that a study by United Nations (UN) agencies in 2018 reported that one in two people in the Philippines experiences some form of food insecurity – for example not having enough food to eat – raising the prospect of a grave situation during the current COVID-19 outbreak.

“We could be facing a humanitarian crisis, unless decisive action is taken. For instance, offering emergency cash subsidies, ensuring access to food and basic services,” added Lasco. “Ultimately the Philippine economy will be hard hit too, just like the rest of the world, but my foremost concern is the informal sector and those for whom ‘no work, no pay’ applies. This is no longer a question of whether we will be affected, but how we will protect those affected the most.”

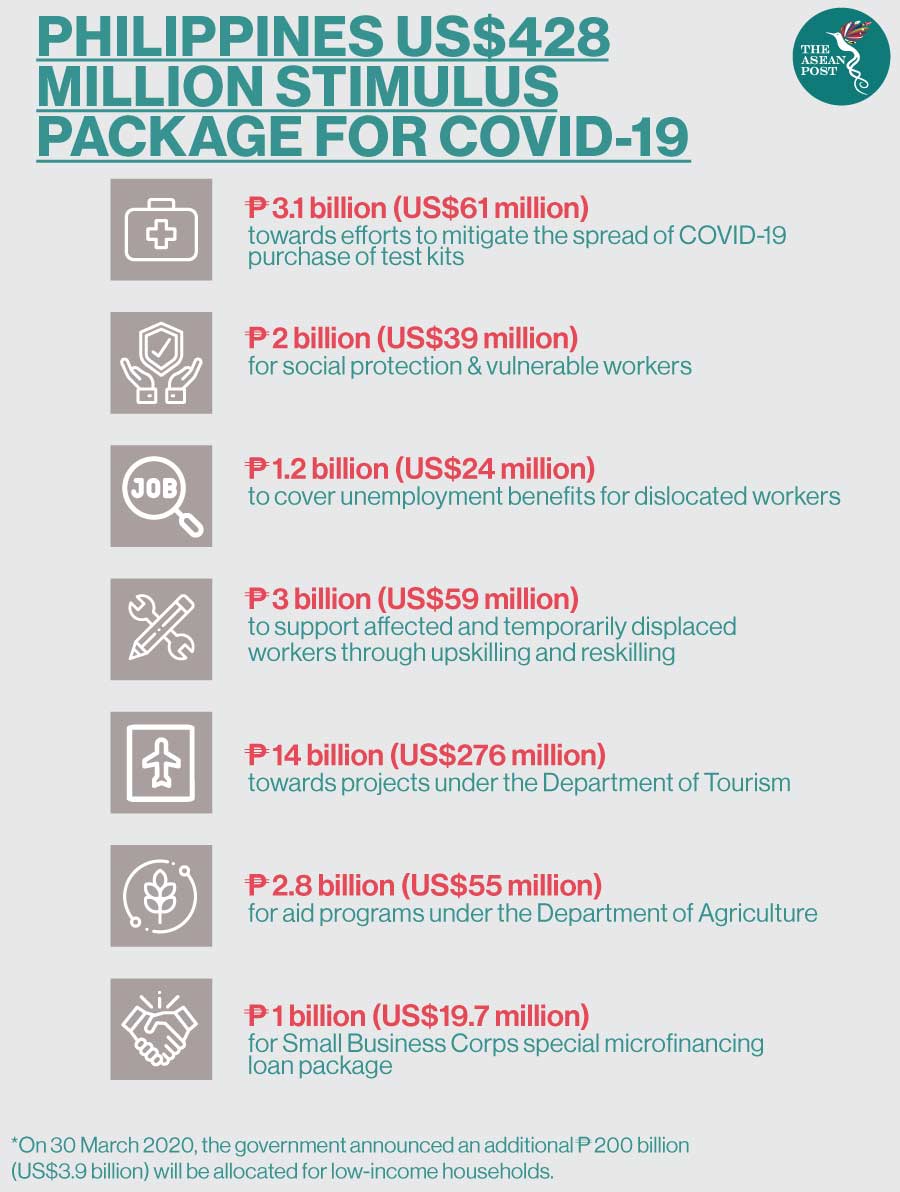

On Monday, the government announced an additional economic stimulus package – the widest and largest social protection program in the country’s history according to Duterte’s late-night broadcast. “We have allotted 200 billion pesos (US$3.9 billion) for low-income households badly affected in this current crisis.”

He said the package was aimed at workers in the informal sector, those who live below subsistence levels and those in “no work, no pay” occupations. His economic team was also developing programs to help farmers and fishermen, as well as small to medium businesses (SMEs).

“We are doing everything we can,” Duterte said, as he paid tribute to health care workers on the frontlines, including at least nine doctors who have died of the disease. Duterte said he had ordered his government to prioritise medical supplies, including personal protective equipment.

Provided that the assistance reaches the population this time, the package could help ease the struggle of millions of families currently unable to afford food. However, the government still needs to step up its efforts in assuring a sufficient supply of food for the entire country for at least six months.

The death toll in the Philippines from the virus as of Tuesday had reached 88, as millions in the country’s main Luzon island enter a third week of forced quarantine.

Related articles: