Just last week, a special online summit was held among Southeast Asia’s leaders to discuss strategies that could be taken at a regional level to combat the deadly COVID-19 pandemic. The new coronavirus has infected over two million people and killed more than 150,000 worldwide. Governments have implemented drastic measures to contain the virus such as travel curbs and citywide lockdowns. Currently, an estimated 4.5 billion people – half of humanity, is under lockdown.

The summit resulted in a joint declaration that included a widely applauded plan to establish a regional COVID-19 response fund to deal with the scarcity of medical supplies caused by the pandemic. The leaders also committed "to keeping ASEAN's markets open for trade and investment... with a view to ensuring food security".

Although the plan is crucial to fighting the pandemic and improving the livelihoods of millions of citizens across ASEAN amid the crisis, it was reported that some organisations criticised the summit as it failed to discuss the plight and wellbeing of refugees and migrants.

“They are part of a group that is vulnerable to COVID-19. It is unfortunate that ASEAN has neglected this,” said Wahyu Susilo from Migrant CARE, a non-governmental organisation (NGO) aimed at safeguarding the welfare of migrant workers, to the media.

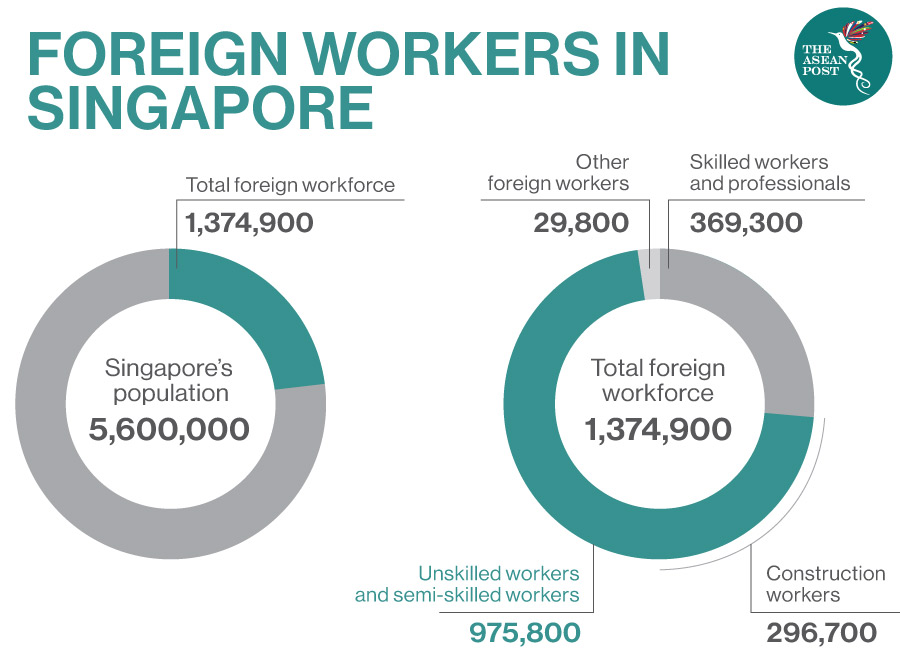

Singapore has been lauded for its gold standard approach in tackling the pandemic. Citizens are given free masks and hand sanitizers courtesy of the state, according to a local media report. Nonetheless, the island’s policies have been focused on Singaporeans only. As of 19 April, more than 6,500 people have been infected in the island state, a majority of whom are migrant workers. Although the fatality rate stands at 11 which is considered relatively low compared to neighbouring Indonesia and Malaysia, its COVID-19 cases have spiked in the past week. On Saturday, it was reported that 942 people were infected in Singapore – the highest recorded number of cases in a single day among ASEAN member states.

It was also reported that there are some 200,000 migrant workers living in 43 dorms in the city-state. As infections rise in these cramped dormitories, thousands of migrant workers are being moved out of the living space. Officials told the media that the workers have now been moved to other sites such as military barracks, vacant apartment blocks and an exhibition site where the Singapore Airshow is held every year.

One of the main issues at these dormitories is the poor living conditions. Workers sleep on bunk beds, 12 to 20 people are crowded into a room, ventilated by small fans attached to the ceiling or walls, according to media reports.

Mohan Dutta, a Professor at Massey University in New Zealand, who has interviewed 45 migrant workers in Singapore since the outbreak started said that the workers claim to not even have access to soap and adequate cleaning supplies at these dormitories.

Former Singapore diplomat, Bilahari Kausikan acknowledged the issue and commented: “We did drop the ball on foreign workers.” However, Josephine Teo, Singapore’s Manpower Minister announced that the country would now adopt a few strategies in handling the recent surge of cases which include locking down dorms with known clusters of infections and isolating those who have tested positive and their close contacts.

Over in Thailand, it has been reported that migrant workers who have lost their jobs are caught in a similar situation, where they can no longer afford to sustain themselves or return home.

As of December 2019, the Employment Department found that there were more than three million migrant workers in the Kingdom – with a majority from Myanmar, Lao, Cambodia and Vietnam. According to the United Nations (UN) Human Rights Office for Southeast Asia, the pandemic has put millions of migrants out of work.

“The biggest problem for migrant workers right now is unemployment,” explained Adisorn Kerdmongkol from Migrant Working Group (MWG), a voluntary network advocating labour rights and welfare.

Adisorn told local media that unemployed migrant workers risk losing their legal status in Thailand should they fail to secure a new job. Without sufficient income, migrants are unable to survive and will often try to return home, he added. However, with Thai border checkpoints closed in order to contain the outbreak, migrants are likely to move around the kingdom in search for jobs or may try to cross the border illegally to return home.

“This won’t benefit Thailand or the country of destination because if the migrants are infected, they could further spread the disease,” Adisorn explained.

Despite criticisms from some migrant rights NGOs, Thailand has been praised by observers for its measures in containing the virus. The country has seen a plunge in COVID-19 cases in recent weeks, with 2,765 cases and 47 fatalities, as of 19 April. It was also reported that just last month, the Thai Cabinet had passed a decision to enable migrant workers who could not renew their work permits in time to continue working legally in the kingdom until the end of June.

Migrant CARE, a non-governmental organisation (NGO) advocating for migrant workers' rights is urging authorities to help vulnerable communities hit hard by the pandemic. “We hope that the Government and authorities will take our plea into consideration in the spirit of humanitarianism. Let us help our fellow human beings in this time of need so that we can all get through this hardship together,” said Alex Ong from Migrant CARE.

Related articles: