To date, over 190,000 people have perished due to the deadly new coronavirus. The COVID-19 pandemic has also severely affected the livelihoods of people around the world. According to the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), overcrowding, poor ventilation, deficient health and poor sanitation conditions “favours the spread of infectious diseases”. These circumstances can be seen in refugee camps, urban slums and also prisons across Southeast Asia.

On 10 April, Amnesty International released shocking footage on social media platform, Twitter –revealing “the inhumane conditions” inside one of Cambodia’s prisons. The organisation called the situation “a ticking time bomb for COVID-19 outbreak” and urged Cambodian authorities to address the overcrowding crisis immediately.

"These deplorable conditions make a mockery of 'physical distancing' and show the Cambodian authorities' utter neglect for these inmates' basic rights, even during a pandemic," said David Griffiths, Director in the Office of the Secretary-General at Amnesty International.

According to the organisation, Cambodia’s prisons held 38,990 people as of 2 April, despite having an estimated total capacity of just 26,593. It was also reported that some facilities were previously estimated to be up to 463 percent over capacity.

Nevertheless, as of 23 April, Cambodia reported 122 cases of COVID-19 with zero deaths, a significantly low number when compared to neighbouring Thailand and the Philippines.

Based on local media reports, when it comes to prison population rates, Thailand has the highest incarceration rate in Asia and the tenth highest in the world.

Just last month, a riot occurred in a Thai jail sparked by fears of a coronavirus outbreak in the facility. Six prisoners were injured and more than 1,500 had to be evacuated before the riot could be halted. It was reported that a group of inmates had started “agitating” other groups with rumours of a virus outbreak.

Over in Indonesia, a similar situation occurred when inmates of Tuminting Prison in the city of Manado went on a rampage after rumours spread among the group that a guard was suspected to have the virus, according to media reports. It was also reported that some inmates had requested for mass testing but were ignored by prison authorities.

Almost 650 people have already succumbed to the deadly virus in Indonesia as of 23 April – the highest number of fatalities in the region. Nevertheless, observers believe the figure could be higher than officially reported.

"Where a prison is so overcrowded and they cannot physically distance people, I can imagine that there will be a high level of anxiety and prisoners would take risks they would not normally take by rioting and making weapons," said Craig Cumming, a research associate at the School of Population and Global Health at the University of Western Australia.

"When such low testing is combined with overcrowding in prisons, the poor areas of Jakarta and even in hospitals, it is inevitable that it was going to cause major problems for the government and virtually explode," Ross Taylor, president of the Indonesia Institute, a foreign policy think-tank at Melbourne's Monash University told the media.

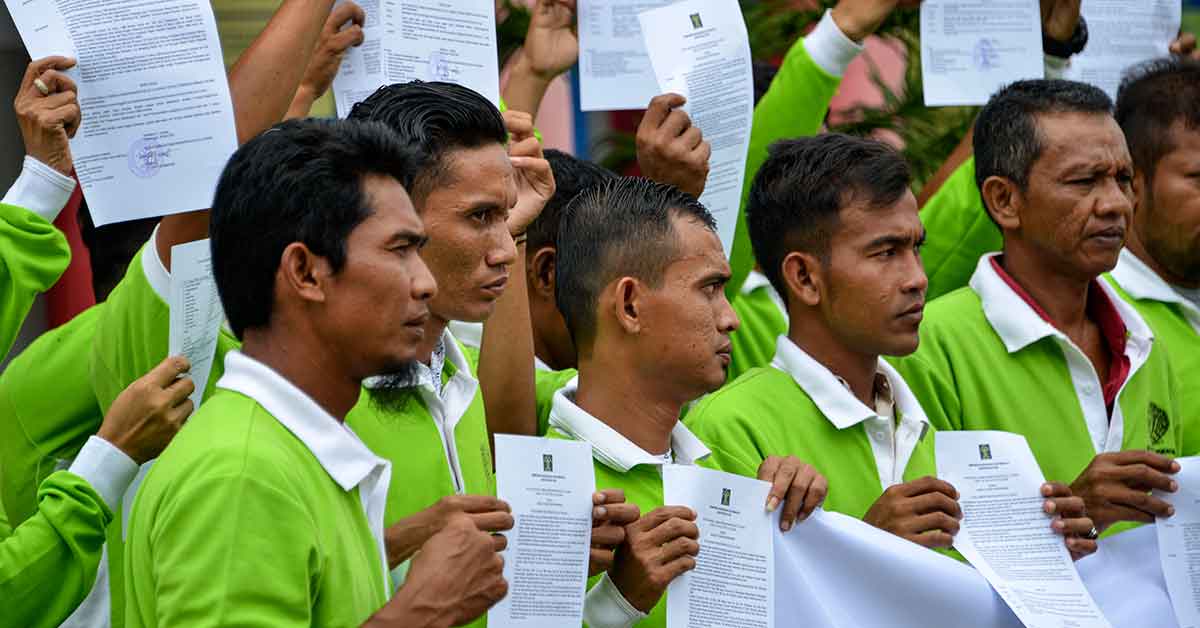

It was reported that the fourth most populous country in the world passed a decree in early April allowing the release of 30,000 prisoners of petty crimes and juvenile delinquents. Officials said that the inmates would be tested for the virus first before being released, and they will still be monitored once out of jail.

"The inmates are vulnerable because most of them share a cell. The risk of contagion is high since our jails are overcrowded," said Nugroho, the acting director-general for correctional facilities in Indonesia. According to media reports, over 270,000 inmates in Indonesia are locked in prisons with a total capacity for only 131,000 people.

Whereas in the Philippines, it was reported that over 100 prisoners have been infected with the COVID-19 virus. President Rodrigo Duterte’s war on drugs has resulted to the country having some of the world’s most overcrowded jails. The Human Rights Watch (HRW) warned of the likelihood of a serious outbreak in the Philippines “threatening the lives of prisoners whose health the authorities have a duty to protect”.

The country has a 464 percent overcapacity rate, the most overcrowded prison system in the world – some of its prisons are over 500 percent capacity, noted the organisation in a statement. In recent days, thousands have been arrested for violating the Philippines’ martial law-like lockdown, making it worse for the overcrowded jails.

Rights groups and organisations have urged for governments to release prisoners “who shouldn’t be in custody in the first place, like political prisoners and those jailed for minor offenses”. HRW also suggested that authorities release older prisoners and those with underlying medical conditions.

Should the authorities agree to an early release of prisoners in order to minimise the risk of COVID-19, or should the inmates remain behind bars as they were convicted of crimes? Some are in a dilemma when it comes to answering the question.

Elie Honig, a United States (US)-based legal analyst and former federal and state prosecutor expressed to the media that “the job is not about locking people up and throwing away the key; it's about protecting the public, even – perhaps especially – in today's extraordinary circumstances.”

Related articles: