Yesterday marked Malaysia’s first day of a Conditional Movement Control Order (CMCO), which is the country’s move to relax its virus lockdown. Malaysia has been under a partial lockdown since mid-March which is due to end on 12 May. The announcement of the CMCO came earlier than expected for most Malaysians as some believe it is “too soon” to curb restrictions as new COVID-19 cases had increased over the weekend.

Nevertheless, Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin said in a special address to the nation that the MCO had seen the country incur RM63 billion (US$14.6 billion) in losses, and if the MCO were to be continued for another month – losses would climb to nearly RM100 billion (US$23.1 billion).

“This is important as business and work is a source of income. If we are under MCO for too long, we will not get any income and this will have a negative impact on our finances.”

Pictures of Malaysians standing in long queues at pawnshops nationwide on the first day of the CMCO were circulated on social media, showing more evidence of the economic impact of the pandemic.

Governments across the world have imposed necessary measures to contain the COVID-19 coronavirus. Although many believe lockdowns and social distancing to be effective in flattening the curve, the restrictions have negatively affected livelihoods, businesses and the general economy.

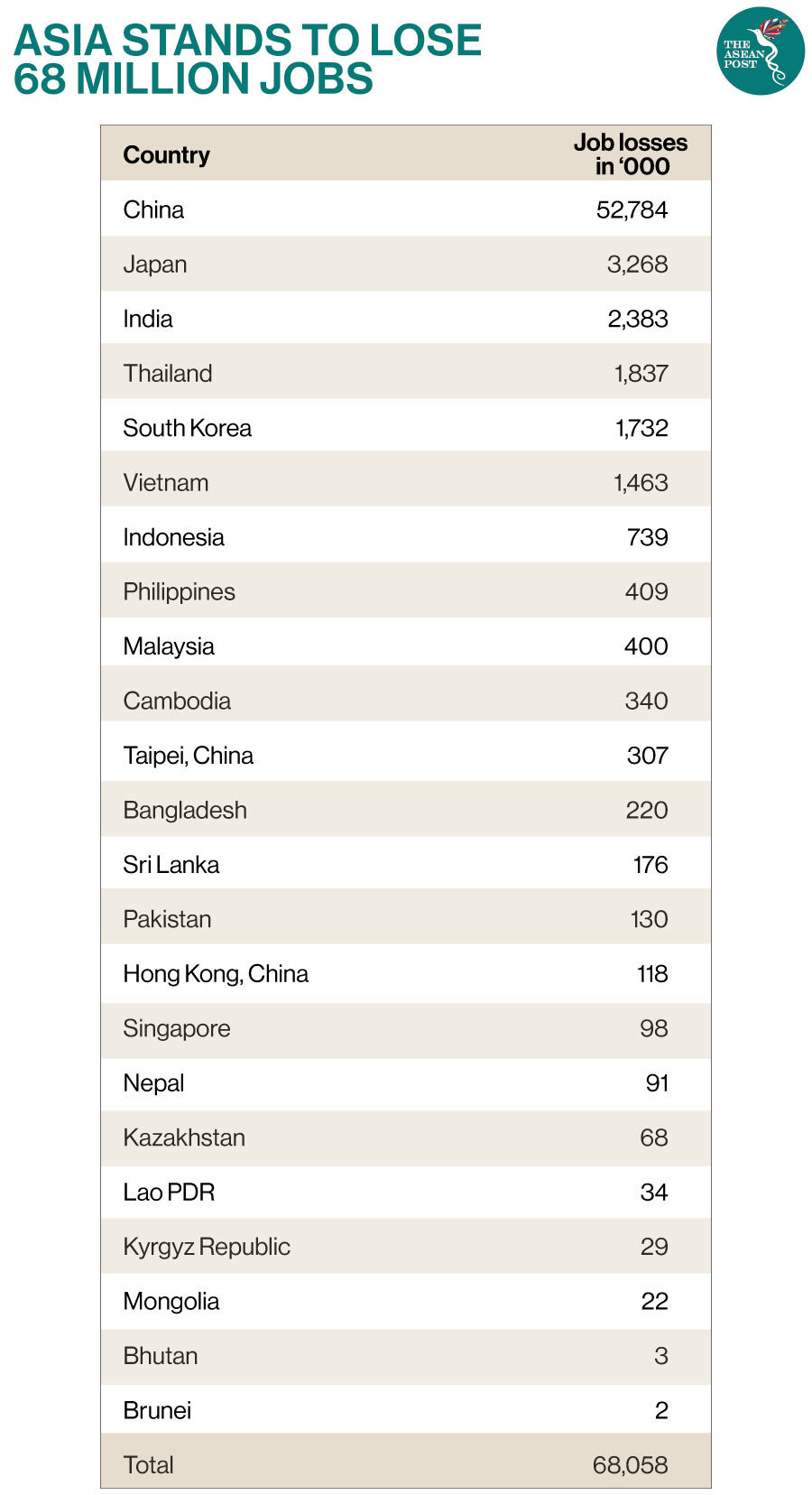

According to the Asian Development Bank (ADB), the pandemic will threaten the employment of 68 million workers across Asia if the outbreak goes on until September.

The conversation about a global recession has been a heated debate among experts and members of the public. Many believe that the worst of the pandemic has yet to come.

Singapore’s central bank told the media recently that a recession in the city-state’s trade-reliant economy could be deeper that forecasted.

"There remains significant uncertainty over the severity of the downturn, as well as the eventual recovery," the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) said in its semi-annual macroeconomic review; adding that "the materialisation of downside risks... could tip the growth outcome in Singapore below the forecast range."

Singapore's hard-hit economy shrank 2.2 percent in the first quarter – its sharpest contraction since the 2009 financial crisis, according to media reports. Neighbouring Malaysia is also reported to be facing the worst economic recession in its history.

Tengku Zafrul Tengku Abdul Aziz, Malaysia’s Finance Minister said during a live special interview that the recession has not only affected the nation’s gross domestic product (GDP), but also contributed towards a rise in unemployment.

Job Loss

Based on media reports, Singapore is experiencing a sharper rise in unemployment compared to the period during the Severe Acute Respiratory System (SARS) outbreak of 2002-2003. As of 4 May, the island-state has more than 18,000 COVID-19 infections – a majority of them migrant workers – with a less than 10 percent recovery rate. The country currently has the highest number of infections in Southeast Asia.

On 1 May, Labour Day, Singapore’s Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong said via a live-stream that the country must brace itself for “significant structural changes” to its trade-reliant economy in the aftermath of the pandemic as “some industries will be disrupted permanently” and “some jobs will simply disappear”. This is perhaps due to the rise of remote work and digitalisation, as reported by local media.

“Workers must accept wage sacrifices to keep businesses going. And employers must make every effort to keep their workers, and help them through this difficult period. They should not drop workers at the first sign of trouble,” said Lee.

Maybank economists Chua Hak Bin and Lee Ju Ye estimate around 150,000 to 200,000 job losses in Singapore this year, even with fiscal aid from the government.

The COVID-19 pandemic could result in not only retrenchments, but also other employment issues such as salary reductions, revoked job offers and unpaid leave.

This can already be seen in the badly affected aviation industry where carriers such as Malaysia Airlines had to go to the extreme, asking 13,000 of its employees to take voluntary unpaid leave starting April. Local media reported that Malaysia’s national carrier had offered all employees the option of either going on three-month no-pay leave or five-day no-pay leave per month for at least three months.

Malindo Airways, a hybrid full-service carrier owned by Indonesia’s Lion Air Group has asked 70 percent of its employees to go on unpaid leave.

A survey conducted by the Department of Statistics Malaysia (DOSM) also found that 46.6 percent of self-employed respondents had lost their jobs following the pandemic. The study also revealed that the agriculture and services sectors recorded the highest percentage of job losses.

Over in Indonesia, the Finance Ministry's head of fiscal policy Febrio Kacaribu told local media that the country could see job losses hitting 2.9 million, due to the outbreak. As of 4 May, the archipelagic ASEAN member state had 11,587 cases of COVID-19 with more than 800 deaths. However, observers believe that the actual figures could be far greater than officially reported.

Relief Measures

Numerous sectors in all ASEAN member states are feeling the pinch from the pandemic. Livelihoods have been affected, while unemployment is on the rise. Governments have rolled out stimulus packages worth billions of dollars to help their citizens, workers and businesses. Singapore announced four fiscal stimulus packages worth a total of SGD63.7 billion (US$44.9 billion), while Thailand approved a fiscal package of THB1.5 trillion (US$46.1 billion) or 8.9 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP). Vietnam has also introduced a fiscal support package valued at VND266 trillion (US$11.4 billion). Moreover, Malaysia has also made available an additional RM4.5 billion (US$1 billion) from its second stimulus package to assist small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in the country.

Some observers have argued that even with all these relief/stimulus packages, there will be some businesses that cannot be saved. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) warned that the pandemic is pushing the global economy into its deepest recession in a century. "The Great Lockdown" – as the IMF called the global downturn – is the worst since the Great Depression of the 1930s.

The severe slowdown is "unavoidable," but "substantial targeted fiscal, monetary and financial" measures can soften the blow and ensure the global economy is in a position to resume once virus lockdowns end, said the IMF.

Related articles: