According to the United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF), 117 million children in 37 countries may not get immunised on time this year. The COVID-19 coronavirus has headlined front covers and news since it emerged in December 2019. To date, more than 3.5 million have been infected with the deadly virus. Last March, the World Health Organisation (WHO) declared the new virus to be a global pandemic.

As the virus looms over the globe while waiting for its next victim, the resurgence of an older disease has raised concerns among health experts amid the pandemic.

Measles is one of the world’s most contagious diseases, with the potential to be extremely severe. Even in high-income countries, complications result in hospitalisation in up to a quarter of cases, and can lead to lifelong disability ranging from brain damage and blindness to hearing loss.

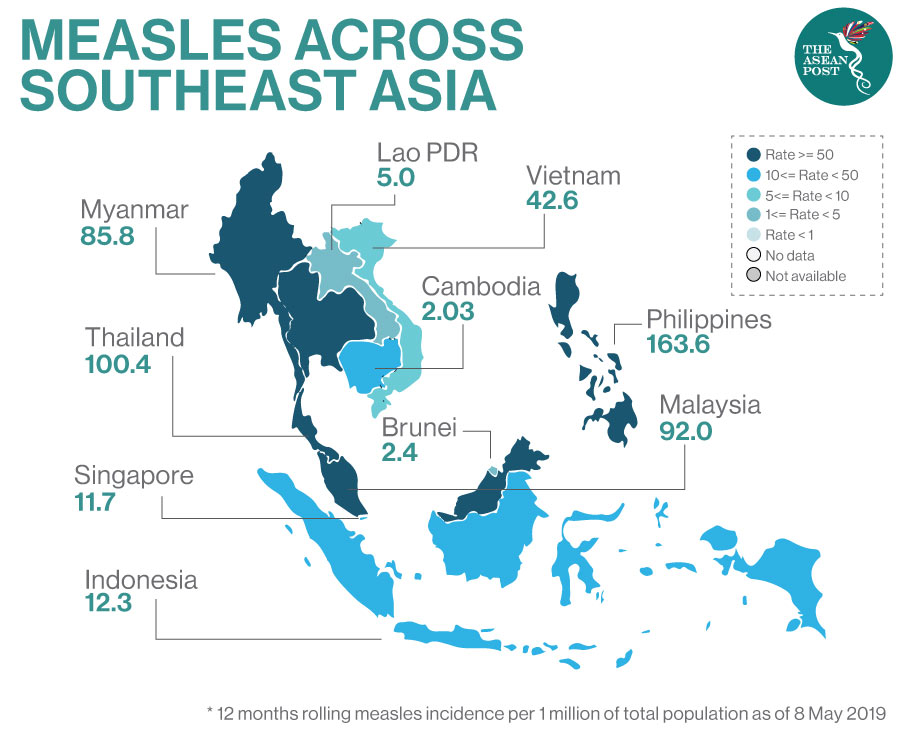

Global data released by the WHO revealed that reported measles cases rose by 300 percent in the first three months of 2019 compared to the same period in 2018. This follows consecutive increases over the past two years and is a worrying trend across the world – especially in ASEAN.

Just last year, there were spikes in the number of cases in Myanmar, the Philippines and Thailand which have caused many deaths – mostly among young children.

The disease is almost entirely preventable through two doses of a safe and effective vaccine. For several years, however, global coverage with the first dose of measles vaccine has stalled at 85 percent. This is still short of the 95 percent needed to prevent outbreaks, and leaves people, in many communities, at risk. The second dose coverage, while increasing, stands at just 67 percent.

With the recent coronavirus, officials warned that measles outbreaks may occur because some vaccination programmes are said to be delayed. Some of the 24 countries which have decided to temporarily pause their immunisation campaigns include ASEAN member state Cambodia, Bangladesh, Somalia, and Nepal among others.

"Disruptions to routine vaccine services will increase the risk of children contracting deadly diseases, compound the current pressures on the national health services and risks a second pandemic of infectious diseases," said UNICEF spokeswoman Joanna Rea.

Over in Malaysia, it was reported recently that there has been a decline in the number of measles cases, from 1,958 to 1,077 last year. However, Malaysia’s Health Director-General, Dr Noor Hisham Abdullah confirmed that measles deaths rose in 2019 compared to the previous year.

“We need more than 95 percent immunisation coverage to provide herd immunity for measles,” he said. Herd immunity refers to a form of immunity that occurs when the vaccination of a significant portion of a population provides protection for individuals who are not or cannot be immunised. This is impacted by the current rise of vaccination refusal by anti-vaccination movements, also known as anti-vaxxers.

No Confidence In Vaccines

Much of the anti-vaxxers’ crusade is driven by a 1998 paper published in The Lancet by British researchers lead by Dr Andrew Wakefield that suggested a link between the MMR vaccine and autism. However, the paper featured only eight children that were selectively sampled and was eventually retracted by The Lancet. The gastroenterologist was later struck off the medical register in 2010 due to fraud for falsified data and financial gain as he was funded by lawyers involved in lawsuits against vaccine-producing companies.

However, for some anti-vaxxers, vaccination refusal for their children could also be based on religious and health beliefs due to components in the vaccine that are derived from porcine sources. For Indonesian state-owned pharmaceutical company PT Bio Farma, this was a call for the development of a halal (permissible by Islamic law) measles-rubella (MR) vaccine. The company is reported to be working hand-in-hand with the Indonesian Ulema Council (MUI) to develop a version of the vaccination that fulfils the criteria set by the Islamic authority.

Although the council said the current vaccine could be used as there were no alternatives, vaccination rates fell in Southeast Asia’s most populous nation to an average of just 65 percent – even falling as low as six percent in Sumatra’s Aceh province.

In the Philippines, a faulty dengue vaccine distributed nationwide dented public confidence in vaccines; causing measles vaccination rates in the country to hover at around 55 percent in 2018.

“The number of cases of measles and other vaccine-preventable diseases has been going up while vaccination rates are going down,” said Edsel Salvana, an infectious diseases physician at the University of the Philippines.

According to reports, for the past three years, the Philippines and Indonesia have recorded the world’s second- and third-highest rates of measles, behind India.

To halt its re-emergence, evidenced-based information is much needed to separate fact from myth surrounding the measles vaccine. After the introduction of the measles vaccine in 1971, deaths caused by the highly transmissible disease were reduced from more than two million to around 100,000 annually. The vaccine has been so effective that we have forgotten what it was like to be plagued by this highly transmissible disease.

Related articles: