2020 is supposed to be a vibrant democratic year for a number of regions in Indonesia. It has been scheduled that on 23 September this year voters in approximately nine provinces, 24 regencies, and 37 cities throughout the archipelago will go to polling stations and decide their next local leaders. But the COVID-19 pandemic suddenly disrupted the highly anticipated political fiesta, forcing the government to postpone local elections to 9 December, 2020.

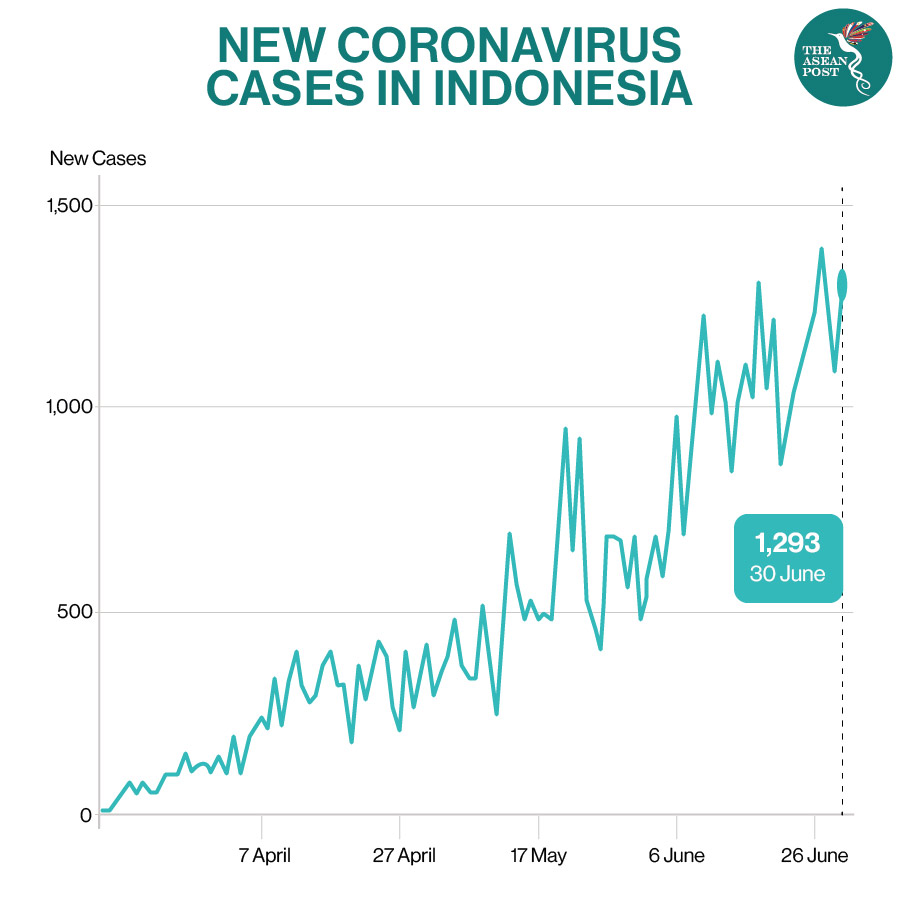

At the time of writing, 56, 385 people across all Indonesia’s 34 provinces have been confirmed positive for the coronavirus and the number is increasing fast by the day. Many of Indonesia’s regions are overwhelmed as they try to mitigate the COVID-19 outbreak. A lack of adequate health infrastructure as well as insufficient medical staff and doctors are among the primary reasons. Local transmission has been reported in some regions and the call to impose nationwide social distancing measures or Pembatasan Sosial Berskala Besar (PSBB) is also growing.

Although the COVID-19 virus is said to have originated in Wuhan, China, it does not mean that Indonesia is safe from becoming the next epicentre for the contagious disease. In fact, the prospects are high should elected regional heads fail to slow down deforestation rates in their respective regions and avoid the clientelistic practices of local politics.

Deforestation And Infectious Diseases

Deforestation plays a significant role in the emergence of infectious diseases. Recent research by the University of Stanford reveals that it is very probable that a contagious disease like COVID-19 will re-emerge. The reason for this is the fact that direct contact between humans and wild animals is now becoming more intensive as a consequence of habitat loss. Previous studies also found that there is a strong connection between deforestation and the increased possibility of an Ebola outbreak in the future.

Long before the COVID-19 and Ebola epidemics, deforestation had caused the spread of malaria in the Peruvian Amazon. In Indonesia, malaria is closely linked to the clearance of the tropical rainforest and mangrove forest. The Nipah virus that killed around 105 people in 1999 and caused recurrent outbreaks in Southeast Asia was also triggered by manmade forest fires in Indonesia.

Regional Heads And Deforestation Rates

Hopes for better forest management were high when Suharto was unseated by a series of vengeful student protests in 1998. Yet the story remains quite the same until today. If during the Suharto years the rate of deforestation was between 550,000 and 1.7 million hectares per year, in the era of ‘reformasi’ (reformation) it stands at 1.47 million hectares. In the last few years (2013-2017) deforestation increased by two percent from the period between 2009 and 2013. Land concessions between 2004 and 2014 was also strikingly high, reaching 9.3 million hectares.

Regional heads have mostly been responsible for this massive forest loss because post-Suharto decentralisation allowed them to issue concession permits. The modus operandi is that a regional head candidate offers a permit to potential investors a few weeks before an election is held. In return, the investors help him with some fresh cash to fund his campaign.

Regional head candidates are indeed permitted by the law to receive a maximum of IDR75 million (US$5,278) of financial assistance from an individual and IDR750 million (US$52,785) from a private business. This contribution does not include the flow of dark money which is difficult to trace.

An Indonesian Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) study showed that corruption related to land and forest concession permits ranked first on the list of types of regional government corruption between 2010 and 2018.

The Need To Avoid Clientelistic Politics

When thick haze was covering much of the skies above Indonesia last year, Indonesia’s regional governments were generally nervous and sluggish to respond. The slow action was due to the clientelistic nature of the relationships between regional heads and the main perpetrators of land fires – plantation companies.

The KPK noted that the primary goal of political financiers pouring billions of rupiahs into the pockets of prospective regional heads, in addition to the ease of access to natural resources, is business protection. Consequently, as expressed by Professor Edward Aspinal in his book titled, Democracy for Sale: Elections, Clientelism, and the State in Indonesia, effective enforcement of environmental regulations in resource-rich Indonesia’s regions such as Central Kalimantan has been undermined.

Furthermore, in the context of the haze, law enforcement is only strict with ordinary citizens, but is lenient when dealing with big corporations. There are many media reports on people who have been arrested and jailed for land burning. Meanwhile, palm oil, pulp and paper companies who have burnt some of the largest areas in the nation remain untouched by the law.

For all these reasons, regional head candidates who will soon be competing for the votes of Indonesians must avoid the politics of clientelism for the sake of forest conservation in the regions they will lead. However, should they decide to continue to perpetuate the vicious cycle; not only will the rate of forest destruction continue to increase, but it will also pave way for the emergence of new infectious diseases like COVID-19 in their respective regions.

Related Articles: