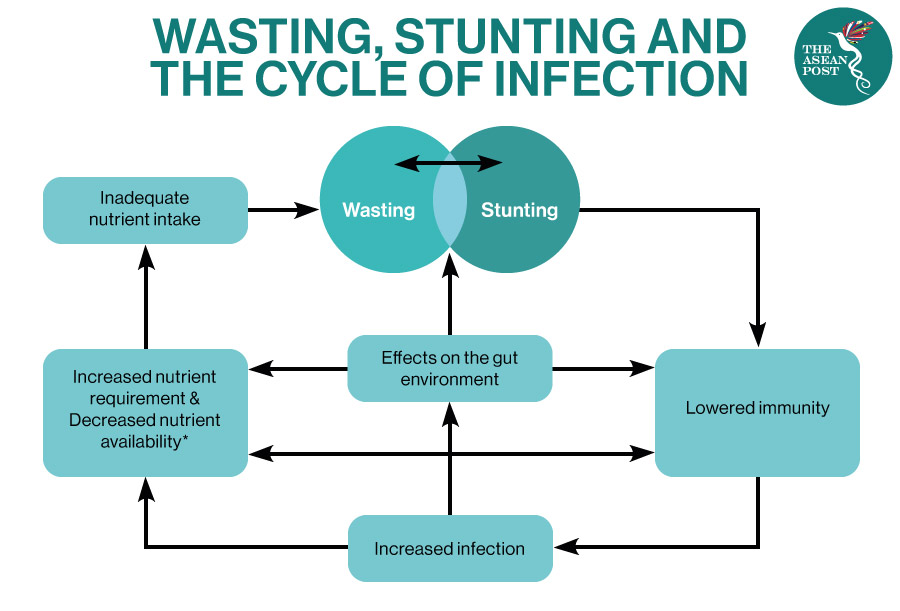

Child wasting is among the most prevalent forms of undernutrition globally. The World Health Organization (WHO) has defined wasting as a low weight-for-height, or thinness due to a severe process of weight loss, often associated with insufficient food intake (nutrient and energy density), and disease. There is growing evidence that a wasted child is more likely to become stunted, and a stunted child is more likely to become wasted, based on a report by the Emergency Nutrition Network (ENN), a United Kingdom (UK)-based registered charity.

The report also noted that the process underlying wasting and stunting involves multiple risk factors and interactions which can change over time. For example, involving poor diet and feeding practices, as well as episodes of infectious diseases and environmental contamination.

The United Nations (UN) estimates that around 47 million children under five were moderately or severely wasted in 2019, most living in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia.

Unfortunately, children who are wasted and stunted concurrently have a multiplicative increased mortality risk. Suffering from both at the same time amplifies the risk of death to levels comparable to children with the most severe form of wasting.

Southeast Asia is home to many wasted children. Nevertheless, it is not recognised as a public health problem and its epidemiology is yet to be fully examined.

A report titled, ‘The Forgotten Agenda of Wasting in Southeast Asia: Burden, Determinants and Overlap with Stunting: A Review of Nationally Representative Cross-Sectional Demographic and Health Surveys in Six Countries’ published in the Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI) -revealed that Cambodia, Lao PDR, Timor-Leste, Myanmar, Thailand and Vietnam have a high number of child wasting cases. The study concluded that a pooled figure of over one million under-five children are affected by wasting, with close to 280,000 of them being severely wasted.

Stunting is also a serious public health problem in the region, with most countries having a stunting prevalence of above 30 percent. Nevertheless, the report notes that despite the coexistence of wasting and stunting in Southeast Asia, less attention has been paid to the concurrence of both.

Despite being one of the wealthier countries in ASEAN, Malaysia is reported to have childhood stunting rates worse than Palestine and some African countries.

According to 2018 World Bank data, Malaysia’s rate of stunting among children under five was 20.7 percent, higher than in Ghana (18.8 percent) and much higher than in Gaza and the West Bank (7.4 percent).

Coronavirus

The UN warned this week that nearly seven million more children will experience stunting as a result of malnutrition due to the unprecedented social and economic crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

“It’s been seven months since the first COVID-19 cases were reported and it is increasingly clear that the repercussions of the pandemic are causing more harm to children than the disease itself,” said Henrietta Fore, Executive Director of the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF).

“Household poverty and food insecurity rates have increased. Essential nutrition services and supply chains have been disrupted. Food prices have soared. As a result, the quality of children’s diets has gone down and malnutrition rates will go up,” she continued.

Local media in Indonesia reported that an overloaded healthcare system, job losses and limited access to food supplies amid the pandemic could exacerbate the already poor living conditions of children deemed most susceptible to stunting and wasting.

In the archipelago alone, more than two million Indonesian children have severe wasting, while more than seven million others under five years old have experienced stunted growth.

The UNICEF predicted that globally, the number of malnourished children under the age of five will perhaps increase by about 15 percent in 2020.

It was reported that US$2.4 billion is needed by humanitarian agencies to protect maternal and child nutrition in the most vulnerable countries till the end of the year. The UN recently released a statement and urged governments, the public, donors and the private sector to protect children’s right to nutrition.

This can be done by re-activating and scaling up services for the early detection and treatment of child wasting, maintaining the provision of nutritious and safe school meals and expanding social protection to safeguard access to nutritious diets.

Related Articles: